Executive Summary

2017 will most likely become a year of important political vintage in Europe. While it already featured elections in the Netherlands, Great Britain and France, all eyes are now on the outcome of the German elections. While many political systems in Europe are under assault of populist challengers, German politics seemingly has been a source of stability. This eupinions report takes a closer look at the contours of German public opinion. It presents two key sets of information. First, it summarizes how the average German citizen thinks about the state of both national and European politics and compares these views to opinions of citizens in the rest of Europe. Second, it outlines differences between Germans who self-identify as left, centre-left, centre-right and right politically.

The main results can be summarized as follows:

Overall, the German public displays high levels of satisfaction with the state of their country as well as their personal situation. 59 per cent think that their country is heading in the right direction, 63 per cent report to be satisfied with how German democracy works, 77 per cent say that their economic situation has stayed the same or even improved (43 per cent same, 34 per cent improved).

Germans become more critical when looking at the European Union. Only 28 per

cent are satisfied with the direction the EU is taking, even though 51 per cent

do think democracy works well on the European level. These numbers however do not translate into a rejection of the German membership in the EU. 75 per cent

of Germans affirm that they would vote remain in a referendum, if given the possibility. And 80 per cent wish to see the EU play a more active role in Global affairs. Ever since the British referendum that let to Brexit, these numbers are on the rise in Germany as well as in the EU as a whole.

These findings point to a highly content and status quo oriented German society and is in stark opposition to the situation of some of their fellow Europeans. Especially Italians seem to be on the other end of the spectrum with high levels of dissatisfaction in almost every of our categories and a growing disdain for the status quo.

These numbers may also lead to believe that the source of German satisfaction is fuelled by the impression that Germany is well off especially when compared to European neighbours and other western allies.

When taking a closer look at the political landscape in Germany, we find that German respondents are far less polarized in terms of their left-right positions than many of their fellow Europeans. Over three quarters of the respondents - namely 80 per cent - classify themselves as centrist (44 per cent

self-identify as centre-left and 36 per cent as centre-right). 12 per cent position themselves on the left, 6 per cent on the right. And only 2 per cent of German respondents identify themselves as extreme left or right.

These numbers are above European average but in line with the results at the EU level. Europeans in general namely 66 per cent, described themselves as centrist, either on the left or right, while only 8 per cent view themselves as extreme left or right. PLEASE NOTE: As the share of respondents who view themselves as either extreme left or right is rather small, we group respondents that view themselves as extreme left or left together as well as those that describe themselves as extreme right and right. This is done in order to overcome problems associated with relying on limited number of observations. Consequently, in the remaining analyses, we discuss four groups of respondents, those on the left, centre-left, centre-right and right.

When it comes to satisfaction with national politics, we find that regardless of people’s ideological leanings a very large majority of German respondents is satisfied with the direction their country is taking, but we do find more differences when it comes to views about the way democracy works in Germany. While a majority of centre-left, centre-right and left respondents are satisfied with the way democracy works in Germany, only 37 per cent of respondents who self-identify as right are satisfied.

This finding is interesting as it suggests that like in many other European countries, discontent with the way the political system works is more pronounced among those on the right of the political spectrum (see our previous report on France for example, de Vries and Hoffmann 2017).

We also find differences based on the ideological leanings of German respondents when it comes to their evaluations of the EU. A majority of those who self-identify on the right or centre-right is dissatisfied with the way democracy works at the EU level (65 per cent right / 53 per cent centre-right)

This scepticism towards the EU among respondent on the political right is also reflected in their vote intentions in a hypothetical referendum on EU membership. While over 80 per cent of left and centre-left respondents would vote for Germany to remain in the EU, the share is much lower among those who see themselves politically on the centre-right, namely 68 per cent. Interestingly, among those who self-identify as right, support for remaining or leaving the EU is 50-50. This is a quite striking difference in political views about Europe. It is of course important to remember that only a small share of German respondents, namely 7 per cent, view themselves as being on the right politically.

Finally, a majority of German respondents, regardless of their left-right ideological views, thinks that the EU should play a more active role in global affairs. This share is over or close to 80 per cent for left-wing and centre-left-wing or right-wing respondents. It is 64 per cent among those who self-identify on the right.

Introduction

After the political upheaval following the Brexit vote, the election of Donald Trump and the successes of populist forces in Europe, all eyes are now set on the German elections taking place on the 24th of September 2017. While other bastions of power seem stricken by considerable domestic political turmoil, German voters might help the party of Chancellor Angela Merkel to win yet another electoral victory. While popular discontent holds a grip on governments in many European Union (EU) member states, disenchantment with politics seems much less pronounced among the German public. Although the rightwing party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) will most likely gain enough popular support to pass the electoral threshold, and enter German parliament, the party is unlikely to achieve a result that is anywhere close to previous electoral successes (like in three German state elections in March 2016 for example). The current German political landscape seems characterized by political stability and continuity rather than change. In this report we compare the opinions of German respondents towards national and European politics with their European counterparts to examine the extent to which they actually differ. Does the German public indeed hold more centrist and less polarizing political views compared to other European publics? Are Germans more satisfied with national and European politics? And finally, what about divisions within the German public, can we detect a touchstone of discontent?

Understanding the contours of German public opinion is important both from an international and domestic perspective. The next German government will play an important role in shaping the future of the EU. German leadership in the EU and beyond is even more important in a time of political uncertainty driven by Brexit, threats to global security, and increasingly isolationist American president. Understanding German public opinion is also important from a national political perspective. Unlike in many other EU member states, populist rightwing parties have failed to reach sustained parliamentary representation at the national level. The entry of the AfD would thus be an historical event, and could fuel growing disillusionment with politics among certain segments of the German population.

In this latest eupinions report, we present evidence based on a survey conducted in July 2017. 10,755 Europeans were interviewed in all EU member states. The sample we analyse is representative for the EU as a whole as well as for the six largest member states in terms of population. In the survey we asked respondents about their views about politics at the national and EU level. This report consists of four parts. In a first part, we explore how the opinions of the German public about the situation in their country differ from those in the EU-28 and the other five larger member states, namely France, Great Britain, Italy, Spain and Poland. Next, we delve into satisfaction with EU politics among the German public, and put it again in a comparative perspective. Third, we explore the share of respondents who view themselves as left and right in Germany compared to France, Great Britain, Italy, Spain and Poland as well as the EU as whole. In a fourth and final step, we examine how German respondents who self-identify as left, centre-left, centre-right or right view both national and EU politics. This overview of German public opinion in comparative perspective provides us with important insights about the extent to which the image of German public opinion as centrist and stable really holds or not.

Politics, personal lifes and the general state of affairs viewed by Germans and their fellow Europeans

In Focus

In our survey we asked people a host of questions about their satisfaction with national politics. In order to examine if and to what extent German public opinion differs from public opinion in other EU countries, we present the results of our survey for German respondents and put it in a comparative perspective. In a first question we asked respondents if they thought their country was overall moving in the right direction. Figure 1 provides an overview of those who answered ‘yes, my country is moving in the right direction’ versus those who answered ‘no, my country is moving in the wrong direction’. While within the EU as a whole only slightly over a third of people, namely 36 per cent, think that their country is moving in the right direction while 64 per cent think that it is not, among German respondents the satisfaction with the direction where Germany is heading is much higher. A majority of German respondents, 59 per cent, think that their country is heading in the right direction, while only 41 per cent think it is heading in the wrong direction. The amount of Germans thinking that their country is going in the right direction has increased in a remarkable fashion over the past few month. In March 2017, only 32 per cent of Germans agreed with their countries direction. In only 4 month this figure almost doubled. In France, this figure is also on the raise. In March, as few as 12 per cent of French people believed their country to move into the right direction. In July 2017 this figure was up by 24 per cent. 36 per cent of French respondant were by then satisfied with their countries direction.

The comparatively high satisfaction in Germany is contrasted with a very low satisfaction about the direction where their country is heading among Italian respondents. In Italy only 13 per cent of respondents think that their country is moving in the right direction, while 87 per cent think that Italy is moving in the wrong direction. Italians display by far the lowest level of satisfaction with the direction in which their country is moving. Overall, about a third of respondents in France and Great Britain, namely 36 and 31 per cent respectively, is satisfied with the direction of their country, while just over a quarter of Spaniards, 27 per cent, think their country is moving in the right direction.

Next, we examine the level of satisfaction with national democracy among German respondents compared to those in the rest of the EU. Figure 2 shows that in the EU as a whole, half of respondents are satisfied with the way democracy works in their country, while half of respondents are dissatisfied. Like in the case of satisfaction with the direction of their country, satisfaction with national democracy is higher among German respondents. While 63 per cent of German respondents report to be satisfied with the way democracy works in Germany, only 37 per cent of respondents state they are dissatisfied. The starkest contrast can again be found with Italian public opinion. On average only 17 per cent of Italian respondents are satisfied with the state of national democracy, while 83 per cent are dissatisfied. In Great Britain a majority of respondents is satisfied with national democracy, 56 per cent, in France it is 50 per cent, while in Spain and Poland a majority is dissatisfied with 54 and 52 per cent respectively.

Finally, we explore economic satisfaction in Germany and beyond. One of the key differences between the current German situation compared to many parts in the rest of Europe is economic stability and growth. The German economy is performing comparatively well and this could spark off more political satisfaction. Figure 3 shows the share of respondents who think their personal economic situation over the past two years has improved, stayed the same or worsened. In the EU as a whole we find very similar shares of respondents across the three different categories. The largest share of German respondents think that their personal economic situation has stayed the same, namely 43 per cent, while only 23 per cent of German respondents think that their personal economic situation has become worse over the past two years. The percentage of people stating that their personal economic situation has become worse in fact is the lowest in Germany compared to the rest of Europe. Satisfaction with one’s personal economic situation is also very high in Poland. 43 per cent of Polish respondents state that their personal economic situation has improved, while 33 per cent think it stayed the same and only 24 per cent think it became worse. As Figures 1 and 2 showed, this economic satisfaction did not necessarily coincide with much higher political satisfaction in Poland like it seemed to do in Germany. Satisfaction with one’s personal economic situation is much lower in Italy, France and Spain where 54, 45 and 40 per cent of respondents respectively state that their personal economic situation became worse over the past two years.

Overall, the German public on average displays much higher levels of satisfaction with national political and economic conditions compared to respondents in the rest of Europe.

Satisfaction with European Politics in Germany Compared to the Rest of Europe

Our survey also included several questions aimed at understanding people’s satisfaction with EU politics and the role Germany plays in it. Figure 4 shows the satisfaction of German respondents with the overall direction of the EU and compares it with the satisfaction within the EU as whole as well as in France, Italy, Spain and Poland. While satisfaction with the direction of their country is higher among German respondents compared to the EU as a whole, satisfaction with the direction the EU is taking is lower in Germany compared to the EU as a whole. While 28 per cent of German respondents are satisfied with the direction in the EU, 34 per cent of EU-28 respondents are. Satisfaction with the direction the EU is taking is higher in France, Spain and Poland compared to Germany with 38, 37 and 36 per cent being satisfied respectively. Like in the case of satisfaction with the direction their country is taking, Italians are the least satisfied with the direction of the EU. Only 17 per cent of Italians state that they are satisfied with the current direction of the EU, while 83 per cent state that they are dissatisfied.

Figure 5 displays the levels of satisfaction with the state of democracy in the EU. The levels of satisfaction with EU democracy in Germany are quite close to the EU average, 51 per cent of German respondents state that they are satisfied while 52 per cent of respondents in the EU-28 say the same. Interestingly, if we compare these levels of satisfaction with EU democracy among German respondents with their levels of satisfaction with national democracy, see Figure 2, we see that Germans are much more satisfied with the way democracy works in their own country compared to the EU, 63 (national) versus 51 (EU) per cent. In the EU as whole people display very little difference between evaluations of national and EU democracy, 50 (national) compared to 52 (EU) per cent. Spaniards and Poles are most satisfied with EU democracy, 61 versus 64 per cent respectively state that they are satisfied with how the EU democracy works. Italians are least satisfied with only 28 per cent of Italian respondents being satisfied with the state of European democracy, this share of satisfaction is however much higher compared to the only 17 per cent who stated to be satisfied with the state of Italian democracy.

Figure 6 displays the share of respondents in Germany and the rest of Europe that state that they would vote for their country to either remain in or leave the EU if a referendum on EU membership were held in their country. While in the EU as a whole 70 per cent of respondents would vote to remain, the share of remain support is slightly higher in Germany with 75 per cent. The support for their country to remain in the EU is even higher among Spanish and Polish respondents with 81 and 79 per cent respectively, and slightly lower in France with 69 per cent supporting remain. The lowest share of respondents stating that they would vote for their country to remain in the EU is found in Italy, here 56 per cent say that they would vote to remain, while 44 would vote to leave the EU.

What about people’s opinions about Germany’s leadership role in the EU? Figure 7 displays the percentage of people who view Germany’s role in the EU as good or bad overall. Within the EU-28, a majority of people, namely 56 per cent, view German leadership in the EU as overall good. Three-quarters of German respondents view their country’s leadership in the EU as positive. While a majority of French and Spaniards are positive about German leadership in the EU, 61 and 52 per cent respectively, only a minority of Italians (31 per cent) and Poles (42 per cent) are positive about Germany’s role.

If we ask people about their views regarding the role the EU should play in global affairs, in the future, respondents across the EU are very positive, see Figure 8. Interestingly, especially the Italians want the EU to play a more active role in global affairs. 87 per cent of Italians do, while 13 per cent do not. A clear majority of Germans would also like to see a more active role played by the EU in global affairs, 80 per cent want a more active role while only 20 per cent do not.

Overall, while the German public displayed much higher levels of satisfaction with national politics compared to the levels in the rest of Europe, they are not necessarily more satisfied with European politics. While a clear majority of Germans would vote for their country to remain in the EU and think that their government is providing good leadership in Europe, they are quite dissatisfied with the overall direction the EU is moving in and with the state of democracy at the European level.

Left-Right Views in Germany Compared to the Rest of Europe

In our survey we asked people which label would best define their political views on a left-right scale: extreme left, left, centre-left, centre-right, right or extreme right. Figure 9 overleaf shows the share of people who place themselves in one of these six categories in Germany and in the rest of Europe.

In the EU as a whole a majority of respondents, namely 66 per cent, describes themselves as centrist, either on the left or right, while only 8 per cent views themselves as extreme left or right. 14 and 12 per cent respectively view themselves as left or right. Interestingly, among German respondents we find that over three quarters of the respondents classify themselves as centrist, 80 per cent do (44 per cent self-identify as centre-left and 36 per cent as centre-right). What is more, the share of those classifying themselves as extreme, either on the left or right, is extremely low among German respondents compared to the rest of Europe. Only 2 per cent of German respondents identify themselves as extreme left or right. Interestingly, in France the share of respondents who view themselves as either extreme left or right is nine times higher compared to Germany, 18 per cent of French respondents classify themselves on the extremes of the political spectrum. In Great Britain, Poland, Spain and Italy left-right polarization is also higher with more respondents on the extremes and less in the centre compared to Germany.

This suggests that compared to patterns in the EU as a whole and the five largest member states, German respondents are far less polarized in terms of their left-right positions. A large majority of German respondents view themselves as centrist. Against this backdrop, the continued support for Chancellor Angela Merkel who has continuously taken a centrist position in the German political debate should come as no real surprise. In the last section of the report, we turn to the question how respondents holding centrist versus more extreme positions differ in their satisfaction with national and European politics. As has become clear from Figure 9, the share of respondents who view themselves as either extreme left or right is rather small, especially in Germany. In order to overcome problems associated with relying on limited number of observations, we group respondents that view themselves as extreme left or left together as well as those that describe themselves as extreme right and right. Consequently, in the remaining analyses, we discuss four groups of German respondents, those on the left, centre-left, centre-right and right. We now turn to the differences in their views about national and European politics.

Satisfaction with National and European Politics Among Left, Centre-Left, Centre-Right and Right Respondents in Germany

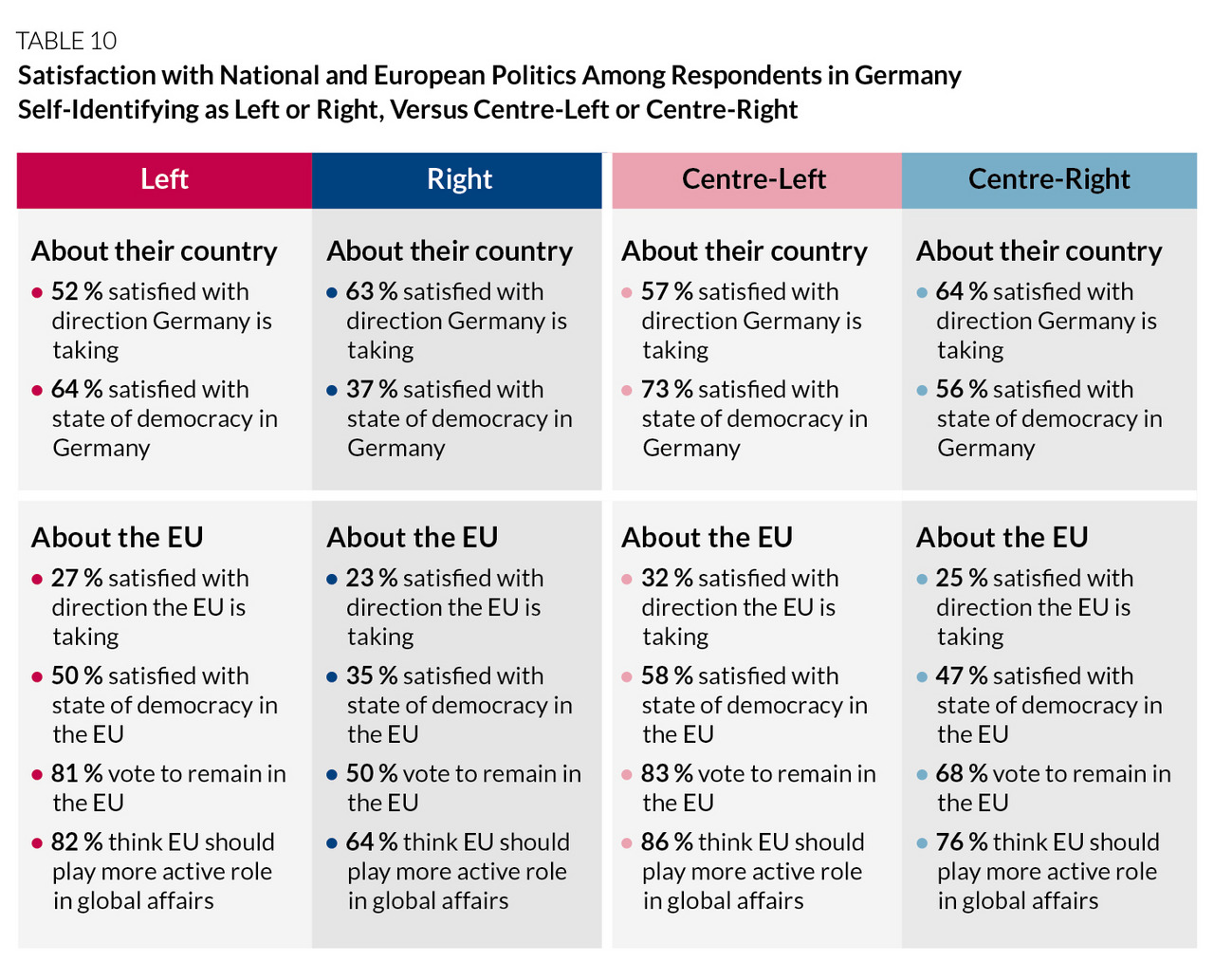

Although the vast majority of German respondents (80 per cent) classifies themselves as centrist, either centre-left or right, it is interesting to explore the extent to which the minority who does not self-identify as centrist differs. In order to examine these differences, Table 10 shows the satisfaction with national and European politics among respondents who self-identify as left or right versus centre-left or centre-right.

When it comes to satisfaction with national politics, we find that regardless of people’s ideological leanings a majority of German respondents is satisfied with the direction their country is taking, but we do find more differences when it comes to views about the way democracy works in Germany. While a majority of centre-left, centre-right and left respondents are satisfied with the way democracy works in Germany, only 37 per cent of respondents who self-identify as right are satisfied. This finding is interesting as it suggests that like in many other European countries, discontent with the way the political system works is more pronounced among those on the right of the political spectrum (see our previous report on France for example, de Vries and Hoffmann 2017).

We also find differences based on the ideological leanings of German respondents when it comes to their evaluations of the EU. While the different ideological groups are all clearly dissatisfied with the direction the EU is moving in, only a majority of those who self-identify on the right or centre-right is also dissatisfied with the way democracy works at the EU level. Only 35 and 47 per cent of respondents who view themselves as right or centre-right respectively are satisfied with the way democracy works in the EU, while 50 and 58 per cent of those who view themselves as left or centre-left politically are satisfied with the workings of the democratic system at the EU level. This scepticism towards the EU among respondent on the political right is also reflected in their vote intentions in a hypothetical referendum on EU membership. While over 80 per cent of left and centre-left respondents would vote for Germany to remain in the EU, the share is much lower among those who see themselves politically on the centre-right, namely 68 per cent. Interestingly, among those who self-identify as right, support for remaining or leaving the EU is 50-50. This is a quite striking difference in political views about Europe. It is of course important to remember that only a small share of German respondents, namely 7 per cent, view themselves as being on the right politically. Finally, a majority of German respondents, regardless of their left-right ideological views, thinks that the EU should play a more active role in global affairs. This share is over or close to 80 per cent for left-wing and centre-left-wing or right-wing respondents. It is 64 per cent among those who self-identify on the right.

While we find that German respondents on average hold very centrist political views and overall seem satisfied with politics at the national level, we do find that those who self-identify on the right are far less satisfied when it comes to the way democracy works in Germany. Moreover, respondents on the right are more sceptical about EU politics. They are quite torn about the membership of Germany in the EU for example. Although the share of right-wing respondents is rather small in our sample, their views do seem to fit some of the patterns that we found for those on the right in France or Europe more generally as well as among supporters of populist right-wing parties in previous reports (see our previous report on France, de Vries and Hoffmann 2017, or globalization fears, de Vries and Hoffmann 2016, for example). There seems a similar albeit comparatively small room for the mobilization of political discontent even in the German context where respondents on average are more satisfied with the state of national politics.

Concluding Remarks

Our findings suggest that in line with the popular image often portrayed about German politics, public opinion in Germany is comparatively centrist and not very polarized. Compared to the rest of the EU, the vast majority of German respondents view themselves as centrist politically, only 2 per cent of German respondents self-identify as extreme left or extreme right. This share is very low in an European perspective, for example the share of respondents that classify themselves on the extremes politically is 18 per cent in France.

What is more, the German public is on average very satisfied with the direction their country is heading in, the state of German democracy and their own personal economic situation. When it comes to evaluations of EU politics, we find a more mixed picture. While support for EU membership and Germany’s role in the EU as well as the EU’s role in the world is high, German public opinion is far less positive when it comes to their evaluations of direction of EU politics and the state of democracy at the European level. This dissatisfaction is most pronounced among those who self-identify as right or centre-right.

Political polarization and discontent thus seems less pronounced among the German public overall, but like in many other European countries we do find that those who self-identify with the right are much less satisfied compared to others. Those who self-identify on the right are more torn about EU membership, 50 per cent would vote to leave the EU while 50 per cent would vote to remain if a referendum was held today, and they are much less satisfied with national democracy, only 37 per cent positively evaluation the state of democracy in Germany. This raises possible future challenges for German politics (for general discussion of these type of challenges, see Foa and Mounk 2016, but also Voeten 2016). If the AfD is able to successfully enter parliament, and perhaps even do better than expected in this election, they would have more institutional means and a formal platform to potentially mobilize some discontent that is building among segments of the population who self-identify as rightwing. The AfD is not a new political force in German politics, they already have a national visibility, but entering parliament could increase it. So far, the AfD has not yet been able to set the political agenda, or dominate the terms of political debate. Yet, in many other European countries, rightwing populist parties have been successfully able to transform their initially small parliamentary force into a more widespread movement rallying anti-establishment sentiment. Gaining parliamentary representation was arguably a crucial step in this process. Populist challengers in Europe have been able to dominate at least parts of the political agenda without having ever set a foot in government, or carry any policy responsibility (Hobolt and de Vries 2015). This allows them to amplify their anti-establishment message. The extent to which the AfD will be able to do this and challenge the centrist tendencies in German politics and public opinion, will be an important thing to watch in German politics the future.

When we look at the big picture we see an image of political stability reflected in German public opinion, yet when we zoom in, we also see some small cracks in the mainstream consensus, especially on right. This means that although the centrist views are predominant among the German public, challenges exist. For example, while most experts expect the party of Chancellor Angela Merkel to win the election, forming a new coalition government might be more challenging then in the past with more anti-establishment players in parliament. Also, while the German public is pro-European in principle, it is at the same time quite dissatisfied with the current direction the EU is taking. The way European reforms are crafted in the future and which proposals can find a consensus among different member states will prove crucially important not only for the EU, but also for the survival of the new German government.

The fact that centrist forces will most likely be at the root of government in both France and Germany could provide a new impetus for Franco-German leadership in the EU. The new German government will have to tread sensitive ground however. The high levels of national satisfaction among the German public are at least in part a reflection of the fact that Germany has been able to profit tremendously from being inside the EU (due to comparatively low interest rates and an under-valued currency for example) even in a very difficult time for the European project both politically and economically. The looming risks for German leadership in the EU are partly a result of the fact that these profits might not have been equally shared within the EU, and people in other member states, especially Italy for example, feel dissatisfied with German leadership. That said, the German political establishment has been able to withstand some of the strong internal pressures of populist politics and anti-EU sentiment that could have drifted its attention away from Europe. Increasing levels of insecurity at the global level and growing support for isolationist positions provide a real window of opportunity for leadership in Europe (or even beyond). If the centrist character of German politics and public opinion could translate into the European arena, the new German government could take on the important role of brokering a consensus between divergent interests and views, and find a way forward for the European project that is shared with other member states.

References

de Vries, Catherine E. and Hoffmann, Isabell (2016) Fears Not Values: Public opinion and the populist vote in Europe. Report for the Bertelsmann Stiftung.

de Vries, Catherine E. and Hoffmann, Isabell (2017)

Is Right the New Left? Right wing voters in France and in the EU and how they differ. Report for the Bertelsmann Stiftung.

Foa, Roberto Stefan and Yascha Mounk (2016)

The Democratic Disconnect. Journal of Democracy 27(3): 5-17.

Hobolt, Sara B. and de Vries, Catherine E. (2015) Issue Entrepreneurship and Multiparty Competition. Comparative Political Studies 48(9): 1159-1185.

Voeten, Erik (2016) That Viral Graph about Millennials’ declining Support for Democracy? It’s Very Misleading. The Washington Post Monkey Cage:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/12/05/that-viral-graph-about-millennials-declining-support-for-democracy-its-very-misleading/?utm_term=.fa28199ccd18

(accessed 7th August 2017).

Method

This report presents an overview of a study conducted by the Bertelsmann Stiftung in July 2017 on public opinion across 28 EU Member States. The sample of n=10.755 was drawn across all 28 EU Member States, taking into account current population distributions with regard to age (14-65 years), gender and region/country. In order to obtain census representative results, the data were weighted based upon the most recent Eurostat statistics. The target weighting variables were age, gender, level of education (as defined by ISCED (2011) levels 0-2, 3-4, and 5-8), and degree of urbanization (rural and urban). An iterative algorithm was used to identify the optimal combination of weighting variables based on sample composition within each country. An estimation of the overall design effect based on the distribution of weights was calculated at 1.46 at the global level. Calculated for a sample of this size and considering the design-effect, the margin of error would be +/-1.1 % at a confidence level of 95 %.