Executive Summary

The political landscape across Europe is changing rapidly: support for populist parties is on the rise while mainstream parties are losing ground. This report examines whether it is fears or values that drive these changes.

Two perspectives dominate popular and scholarly interpretations of what is the matter in Europe today. One stresses a conflict between progressive and traditional values while another stresses the divide between those that benefit from globalization versus those left behind. When it comes to values, the argument is that elites have pushed forward liberal rights, like gender equality, gay rights, ethnic diversity, environmental protection, etc. against the will of ordinary people. In that view, current support for populist parties is the result of a revolt against a liberal elite that is out of touch. A second argumentation stresses the economic fallout of globalization, and suggests that a growing number of people fear to be left on the sidelines.

Our findings show that fear of globalization is the decisive factor behind demands for changes away from the political mainstream. Values play a minor role. In a nutshell we find that: The lower the level of education, the lower the income, and the older people are the more likely they are to see globalization as a threat. Moreover, those who feel close to populist parties are mainly motivated by fear of globalization. This effect is particularly evident when it comes to right wing populist parties, but it is also present for left wing populist parties. For example: In Germany, 78 per cent of supporters of the right wing Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) fear globalization. In France, 76 per cent of Front National (FN) voters fear globalization. In Austria, 69 per cent of Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) supporters fear globalization.

Some of the figures that stand out in our report:

- Europeans are almost equally split when it comes to how they view globalization. A slight majority sees globalization as an opportunity (55 per cent), while 45 per cent see it a threat. 35 per cent of respondents are economically anxious, while 65 per cent are not.

- We find considerable country differences when it comes to globalization fears. In Austria and France a majority of respondents view globalization as a threat (55 per cent, 54 per cent). French and Italian respondents display the highest level of economic anxiety with 51 per cent and 45 per cent respectively. In the UK, the amount of people who feel economically anxious and see globalization as a threat is particularly low with only 26 per cent and 36 per cent. Even fewer people are economically anxious in Poland, namely 22 per cent, but Poles are on average wearier of globalization (50 per cent).

- Age, class, and education are relevant variables to understand fears of globalization and economic anxiety. With 47 per cent and 38 per cent of those identifying themselves as working class saying that they perceive globalization as a threat versus only 37 per cent and 25 per cent of middle class people. Also, 47 per cent and 37 per cent of people with lower levels of education express worries about globalization and their economic situation versus 37 per cent and 28 per cent among those with higher education. When it comes to age, the numbers indicate that the younger you are, the less you worry about the effects of globalization and your economic future (ranging from 39 per cent and 30 per cent of 18–25 year olds to 47 per cent and 41 per cent of 56–65 year olds). Gender or whether one lives in an urban or a rural environment hardly makes any difference on one’s perception of globalization or one’s personal economic situation.

- For those identifying with right wing challenger parties in Europe globalization fears are very pronounced. 78 per cent of AfD voters, 76 per cent of FN voters, 69 per cent of FPÖ voters, 66 per cent of Lega Nord voters, 57 per cent of PVV voters, 58 per cent of PiS voters, 61 per cent of Fidez and 50 per cent of Jobbik voters and 50 per cent of UKIP voters see globalization as a threat

- Left wing populist parties, such as Die Linke, Five Star Movement, and Podemos, also attract people who fear globalization, but interestingly to a lesser degree.

- When we examine more generally what people think politically depending on if they are fearful of globalization or not, we see that people who fear globalization are much more suspicious of politics in general and European integration in particular: They are more likely to support leaving the European Union (47 per cent) in a referendum, and hardly like the thought of more European integration (40 per cent). Only 9 per cent trust the politicians in their country, and 38 per cent are satisfied with how democracy is working in their country. Moreover, 57 per cent of people who are fearful of globalization think that there are too many foreigners in their country, but only 29 per cent oppose gay marriage and 34 per cent think climate change is a hoax.

- When we contrast these numbers against those who think globalization is an opportunity, we find that 83 per cent would vote for their country to stay in the EU, 60 per cent think more integration is the way forward for the EU, 20 per cent trust their national politicians, and 53 per cent are satisfied with democracy in their country. Moreover, less people, namely 40 per cent, think that there are too many foreigners in their country, 19 per cent oppose gay marriage and 28 per cent believe that climate change is a hoax.

- In a final step, we examined what people fear specifically about globalization. We asked what respondents think the major political challenges in the years to come will be. When it comes to economic crisis, poverty, terror, war, and crime the differences between those who fear globalization versus those who do not are minor. Only when it comes to migration do we find a clear difference between the two groups: 53 per cent of those who fear globalization think that migration is a major global challenge, 55 per cent are not in contact with foreigners in their daily lives, and 54 per cent display anti-foreigner sentiments. While only 42 per cent of those who see globalization as an opportunity think migration is a major global challenge, only 43 per cent do not have any contact with foreigners in their daily lives and even fewer, namely 36 per cent, express anti-foreigner sentiments. These patterns for the EU as a whole also hold true for the nine countries we studied in more detail.

Traditional Values and Globalization Fears: Setting the Scene

In Focus

The election of the real estate mogul and politically inexperienced Donald Trump as the President of the United States of America and the outcome of the Brexit vote in the United Kingdom have sent shock waves across the globe. Politics in many countries today seems to be undergoing a transformation. Mainstream politicians are challenged by political outsiders who accuse them to be largely out of touch with the needs and wants of ordinary citizens. Surely, accusations of this kind are politically motivated, but the reactions of much of the public to years of economic and political liberalisation seem to be out of step with the actions of their governments. Government parties are increasingly pushed in a corner and need to find ways to respond to growing discontent.

One such response was British Prime Minister Theresa May’s attack against the political establishment for sneering at voters’ concerns about free movement of people in the EU and immigration at her first Tory Party congress in Birmingham, “just listen to the way a lot of politicians and commentators talk about the public. They find their patriotism distasteful, their concerns about immigration parochial, their views about crime illiberal, their attachment to their job security inconvenient.” [1] The outcome of the Brexit vote, the support for Trump or the strong electoral showing for populist parties on the left and right, such as Front National in France, the Partij van de Vrijheid in the Netherlands, Die Linke in Germany or Podemos in Spain, are interpreted by politicians and pundits alike as a revolt against politics as usual. Yet, what are voters revolting against?

Two answers to this question seem to have emerged in the popular and academic debate: traditional values and globalization fears (Inglehart and Norris 2016). One stresses the importance of traditional values and argues that liberal elites have stretched their economical, political, and cultural ideas too far. As a response a large segment of the population demands a correction. Traditionalism, or something political psychologists define as authoritarianism, captures people’s desire for order and stability over flexibility and change. Traditionalists or authoritarians prefer strong leaders that preserve a status quo and impose order on a world they feel is under threat (Feldman 2003, Hetherington and Weiler 2009). Articles like “Donald Trump and the Authoritarian Temptation” in the Atlantic in May 2016 highlight that the current political upheaval is largely a conflict over liberal versus authoritarian values.[2]

A second answer does not so much stress the socio-cultural basis of public opinion, but the economic nature of it. People feel left behind by globalization and that political elites no longer look out for them. People support political outsiders who skilfully articulate their fears about globalization linked to their economic situation and skill competition by immigrants. In his book the Globalization Paradox, Dani Rodrik (2011) for example argues globalization presents a trilemma as societies cannot be globally integrated, completely sovereign and democratic at the same time. Following his reasoning, deeper economic integration accompanied by further political integration in Europe would likely lead to resistance amongst the most vulnerable demanding a fair distribution of wealth and jobs, and for their government to take back control. The Brexit vote in the UK as well as the election of Donald Trump as President of the United States have been attributed to a revolt of those left behind in the popular media. [3]

Although traditional values and globalization fears are not mutually exclusive, and may in fact be linked, in this report we aim to shed light on the distribution of these values and fears in the 28 member states of the EU, and examine whether fears or values are the most important for explaining the political shifts we have witnessed recently. Understanding if fears or values guide people’s support for populist parties, the exit of the EU, and their trust in government, is important as it provides us with more detailed insights about what exactly people worry about. Responding to voter’s concerns is important, but politicians are only able to do so when the exact contours of public opinion are well understood. For example, while values are often perceived as more long-standing, fears might be more dynamic in nature and hence both require different policy solutions.

In this report, we present evidence based on a survey conducted in early August asking people about their traditional values and globalization fears. We present two types of evidence; one type is based on a sample capturing public opinion in the EU as a whole, and the other completes the picture by focusing on nine EU member states representing the North-West, South, and Central-East European regions.

In the following sections we seek to answer four questions:

- How are globalization fears and traditional values distributed within the EU

- Who are the people who fear globalization or display traditional values?

- What do people who are fearful of globalization or have more traditional values want in terms of politics?

- Finally, what do those who are wary of globalization fear exactly?

Our findings suggest that traditional values and globalization fears split public opinion in the EU: 50 per cent of people can be classified as traditional or fearful of globalization, while 50 per cent are characterized by progressive values and a belief that globalization constitutes an opportunity. Importantly, however, we find that fears rather than values structure the political answers people would like to see and the political party they turn to. Those who fear globalization are much more likely to vote for extreme right parties, to want to exit the EU, or be more sceptical of politicians and foreigners. Values only matter for people’s responses to questions tapping into policy issues like gay marriage or climate change. That said, however, even within the traditional group only a very small minority of people opposes these issues, and they are currently not the most salient in the political debate. After we have established that globalization fears rather than traditional values structure what people want from politics, we delve deeper into what exactly it is that people fear. We find that migration is people’s biggest concern, and while fears about migration are most pronounced by those who are fearful of globalization, they also have much less contact with foreigners than those who see globalization as an opportunity. Before we dig deeper into our results, we will outline the items we used to capture people’s traditional values and globalization fears.

[1] See: www.ft.com/content/81944540-8a56-11e6-8cb7-e7ada1d123b1(accessed 6th October 2016).

[2] See: www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2016/05/trump-president-illiberal-democracy/481494/ (accessed 6th October 2016).

[3]Fear not Values. See: www.newstatesman.com/politics/uk/2016/08/city-left-behind-post-brexit-tensions-simmer-bradford (accessed 6th October 2016).

Measuring Values and Fears

Measuring concepts like traditional values and globalization fears in a survey is far from straightforward, and many different authors have taken different approaches. Our approach here is to rely on a set of questions tapping into the two basic concepts we are interested in; traditional values and globalization fears. In this section we aim to be transparent about the choices we made.

Traditionalism, or authoritarianism as it is known with political psychology, is a tricky concept that has inspired a large literature in psychology and political science. Asking people about the degree they adhere to traditional values is a difficult exercise as people may not wish to admit this or are not aware of it. We follow a measurement strategy set out by renowned political psychologists Feldman and Stenmer (1997) who tap into traditional authoritarian values by relying on a battery of child-rearing questions.

Specifically, we rely on:

- Please tell me which one you think is more important for a child to have: independence, or respect for elders?

- Please tell me which one you think is more important for a child to have: obedience, or self-reliance?

- Please tell me which one you think is more important for a child to have: to be considerate, or to be well-behaved?

- Please tell me which one you think is more important for a child to have: curiosity, or good manners?

These questions are less prone to social desirability, and not as conceptually linked to the consequences of values that we are interested in. This measurement has now become common practice. We create an additive measure that runs from a belief that children should always be well-behaved, obedient and respectful of elders to a belief that they should be independent, responsible and curious (see Kohn 1977 for a discussion). We combine the answers to the following four questions to create an additive scale where 1 signifies “most traditional” responses as people always responded that children should be well-behaved, obedient and respectful of elders, and 0 signifies “least traditional” responses as people always responded that children should be independent, responsible and curious.

There is not an established tradition to measure people’s fears of globalization, so we rely on questions dealing with globalization and people’s economic anxiety.

Specifically, we rely on the following three questions:

- Do you think that globalization is a threat or an opportunity?

Answers are coded as 1 if people think it is a threat and 0 if an opportunity. - An economic anxiety measure which combines of answers to two questions where 1 is coded negative and 0 is coded positive:

– How has your economic situation changed in the last two years?

– In general what is your personal economic outlook on the foreseeable future?

All measures used in the analysis are coded between 0 and 1 to ease interpretation, so the numbers in the graphs can be interpreted as percentages.[4]

[4] Note some questions allowed a ‘don’t know’ option and these respondents are excluded in the values presented.

How are Values and Fears Distributed Within the EU?

How are globalization fears and traditional values distributed across the EU? Figure 1 displays the percentage of people who display traditional values, and express that they see globalization as a threat and are economically anxious. The figure shows that a substantial part of citizens in the EU are fearful of globalization, but that this is still a minority over the overall population. Specifically, we see that 45 per cent of people see globalization as a threat, while 55 per cent see it as an opportunity, 35 per cent of people report that they feel economically anxious while 65 per cent report that they are not, and 50 per cent of people display traditional values, while 50 per cent do not.

In a next step, we explore globalization fears and traditional values in nine specific countries for which we have conducted a more in-depth study. Figure 2 shows quite substantial variation across countries. While in Austria and France a majority of citizens see globalization as a threat, 55 and 54 per cent respectively, this share is lowest in Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, and the United Kingdom (with 39, 40, 39 and 36 per cent respectively). The low share of British respondents who think that globalization is a threat is especially interesting given that the current Prime Minister has suggested that the Brexit vote was mainly a result of people feeling left behind by globalization. The level of economic anxiety is in fact relatively low in the UK, only 26 per cent say that they are economically anxious, in comparison to some other EU countries. Economic anxiety is very high in Italy as well as in France with half of the population (45 and 51 per cent respectively) stating that they are worried about their economic situation.

When we look at the distribution of traditional values across the nine different countries, we find that just like in the case of globalization fears there is considerable variation in the degree of traditionalism. We find the highest levels in France, Poland, and the United Kingdom, where 55 per cent of the population holds more traditional values, and the lowest levels in Austria, Germany, and Hungary (with 38, 39 and 38 per cent respectively).

Overall, the findings presented thus far suggest that notwithstanding important country variation, on average Europeans are split when it comes to their views about globalization, and their level of traditionalism. 45 per cent see globalization as a threat and 50 per cent display traditional values. Moreover, two-thirds do not feel particularly anxious about their economic position while one-third do.

As previously stated, the following graphs will show that the fear of globalization and economic anxiety help to explain recent outcomes of elections and the shift in the political debate in Europe, whereas the level of traditionalism in societies does not seem to be a decisive variable to explain the populist vote. Whatever outcome we look at traditional values seem quite evenly split.

Who Fears Globalization and Displays Traditional Values?

In the next step, we delve deeper into the distribution of globalization fears and traditional values by exploring differences across individuals rather than countries. Specifically, we explore how these fears and values are dispersed across class identification, education level, the age, residence of respondents, and gender. We present the variables in order of pertinence. The most notable differences exist when we look at social class, education, and age. Residence and gender only show minor differences.

Pitting the fears and values of the working class against those of the upper middle class yields more significant differences, as seen in Figure 3. While 38 per cent of the working class say that they feel economically anxious, only 25 per cent of those identifying as middle or upper class do. The second largest difference between social class identification is based on seeing globalization as a threat; 47 per cent of the working class do while 37 per cent of the middle and upper class do. In respect to traditional values those who identify as working or middle/upper class display very similar leanings (51 versus 48 per cent respectively.

When we turn our attention to people’s level of education, we find more differences. High levels of education include respondents who have attained a vocational, university or doctoral degree; while lower education signifies those with a high school diploma or less. Figure 4 shows stark differences between the differing levels of education when it comes to their fears of globalization. At 37 per cent, the higher educated are less likely to see globalization as a threat compared to the lower educated with 47 per cent. Also, the higher educated are less likely to be economically anxious compared to the lower educated, 28 versus 37 per cent. Interestingly, people’s level of education makes less of a difference for traditional values. With 51 per cent versus 45 per cent of the low versus highly educated displaying traditional values, we find little difference in traditionalism based on education.

Figure 5 displays globalization fears and traditional values by age cohorts. Younger cohorts are slightly less fearful of globalization, but the differences between the age cohorts are rather small. The younger cohorts do not differ in any ways from older generations when it comes to their level of traditionalism. Younger cohorts do differ in terms of economic anxiety. They are less anxious compared to older generations. This is not entirely surprising given that those under age 35 might not yet think about old age insurance and pensions. So except for economic anxiety, age does not seem the driving force behind globalization fears and traditional values.

Finally, we inspect differences based on whether people live in rural or urban areas. Figure 6 shows that people living in rural areas do not differ substantially from those who live in urban areas, except that people in rural areas are somewhat more likely to report that globalization is a threat (51 per cent for rural inhabitants versus 42 per cent for city inhabitants).

Figure 7 displays the differences between men and women in expressing that they are fearful of globalization or hold traditional values. The numbers for women and men are remarkably similar, we find that women are slightly more economically anxious, 38 per cent of women versus 32 per cent of men, and score slightly lower in their overall level of traditionalism (47 per cent for women versus 52 per cent for men).

The inspection of how globalization fears and traditional values are distributed across socio-demographics indicates that most substantial differences exist based on people’s age and level of education. Younger people and those with higher levels of education seem to display less fearful attitudes of globalization, although the differences in terms of traditional values between the young and old, and high and low educated respectively, do not seem very pronounced.

What Do People Who Fear Globalization or Display More Traditional Values Want Politically?

After having established how globalization fears and traditional values are distributed geographically and across individuals background, we now turn to the so what question. Do those who fear globalization or display more traditional values have different political desires? In table 1 we contrast people who think globalization is a threat against those who think it is an opportunity to see how they think about the EU, their national system and some key policy issues.

People who think globalization is a threat versus those who believe it is an opportunity have fundamental differences in their thinking about the EU and their national system. While 47 per cent of those who fear globalization would vote for their country to exit the EU if a referendum were to be held in their country, 83 per cent of those who believe globalization is an opportunity would vote to remain. While the majority of those who view globalization positively wish to see more political and economic integration in Europe (60 per cent), only 40 per cent of those who fear globalization do. The majority of those who think globalization is an opportunity are satisfied with how democracy works in their country (53 per cent), only a minority, namely 38 per cent, of those who fear globalization are satisfied. Although only a minority of people say that they trust politicians, it is twice as high for those who view globalization positively (20 versus 9 per cent respectively). Finally, those who evaluate globalization negatively are more likely to oppose gay marriage, think that climate change is not real, and feel that there are too many foreigners in their country compared to those who view globalization as an opportunity, but the differences for gay marriage and climate change are much smaller compared to foreigner sentiment.

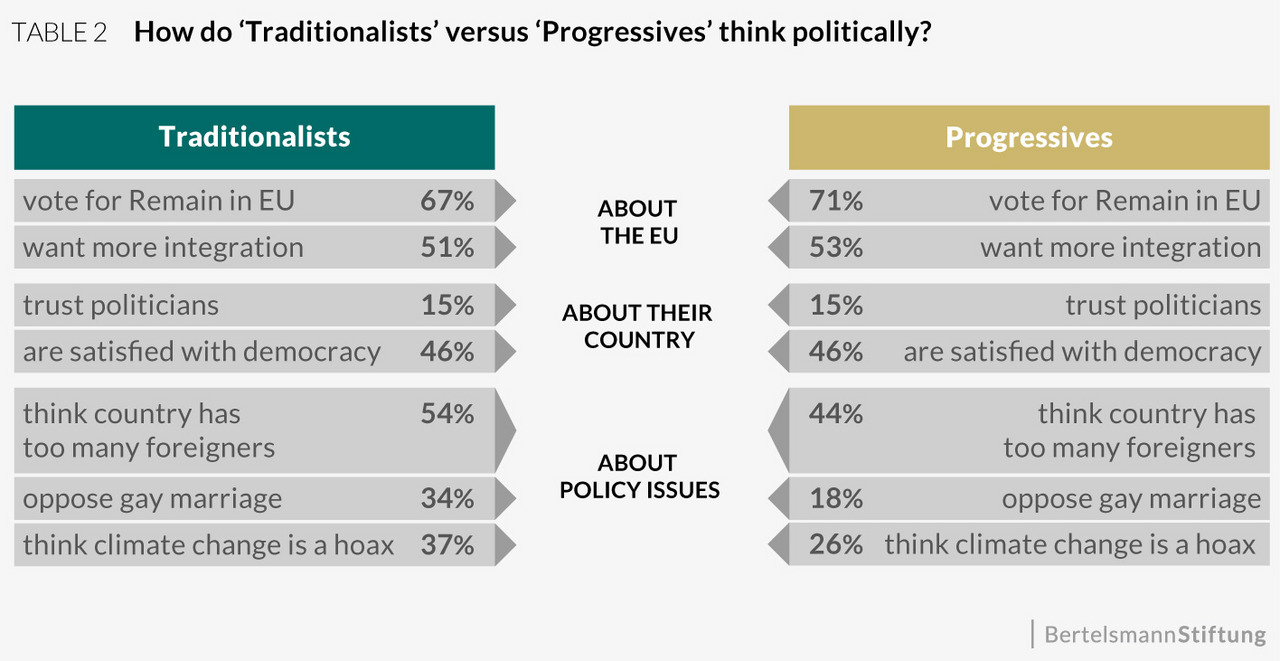

Table 2 provides the same contrast analysis as Table 1 but for people who hold traditional versus progressive values. Interestingly, and in stark contrast to our fear results, traditionalists and progressives do not differ very much when it comes to their opinions about the EU and their national systems. The majority of traditionalists and progressives would vote for their country to remain a member of the EU in a referendum, and wish to see more integration. They display equal amounts of trust in politicians and satisfaction with democracy (15 versus roughly 46 per cent). Where traditionalists and progressives do differ is in their views about immigrants, gay marriage and climate change. Traditionalists, like those who think globalization is a threat, are much more likely to say that there are too many foreigners in their country, think that climate change is a hoax, and oppose gay marriage.

So far, our findings suggest that globalization fears rather than traditional values coincide with stronger scepticism about both national and European politics, as well as more opposition to gay marriage, the idea of climate change, and foreigners living in one’s country. Traditional values do matter for people’s views on foreigners, gay rights, and climate change, but present a very similar picture of opposition compared to those who are fearful of globalization.

Of Those Who Say They Fear Globalization – or Display More Traditional Values – Which Party do They Feel Close to?

In a next step, we delve deeper into how people who fear globalization or exhibit traditional values think about politics, by inspecting which party they feel close to. Here we rely on the data we have collected for nine specific member states. The single most important information that emerges when analysing party preferences is that people who fear globalization massively choose right wing populist parties. Figure 8 assembles the right wing populist parties in nine European countries. The clear majority of their supporters fear globalization. In Germany this majority is as large as 78 per cent. In France it is 76 per cent. In Austria it is 69 per cent. In Italy it is 66 per cent. In the Netherlands it is 57 per cent. In Hungary it is 61 per cent. In the UK it is 50 per cent. And in Poland it is 58 per cent.

Voters of left wing populist parties also feel threatened by globalization — but to a lesser degree. Figure 9 shows that fear of globalization is highest with La Gauche in France (58 per cent), followed by Die Linke in Germany (54 per cent). Next is the Five star movement in Italy (48 per cent), the Hungarian MSZP and SP in the Netherlands (both with 45 per cent) and finally Podemos in Spain with 43 per cent of supporters in fear of globalization.

In the following, we will present the results country by country and for each significant party in all these countries. Figure 10 shows how globalization fears and traditional values are distributed for those who feel close to specific parties in Germany. It shows that identifiers of the right wing populist party Alternative for Germany (AfD) differ from their counterparts more in terms of their globalization fears than traditional values. They are much more likely to be economically anxious and to think that globalization is a threat, while they display similar levels of traditionalism as those who identify with the Christian Democrats CDU. Interestingly, AfD identifiers share similar characteristics compared with those who identify with the Left Party (Linke), except for their traditional values. Linke identifiers are far less traditional than AfD identifiers. Identifiers of the Social Democratic party (SPD), Liberal Party (FDP) and the Greens (Bd90/G) are very similar in terms of their globalization fears and traditional values.

Figure 11 shows the globalization fears and traditional values for party identifiers in the United Kingdom. Interestingly, we find that the right wing United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), centre left parties Labour (LAB) and Scottish National Party (SNP) identifiers share a similarity, they are all much more economically anxious compared to the centre right parties Conservative (CON) and Liberal Democratic (LibDem) party identifiers. UKIP identifiers are much more likely to fear globalization than CON, LAB and LibDem identifiers. SNP identifiers are also slightly wearier of globalization with 41 per cent stating that they are fearful of globalization. UKIP identifiers are more likely to think this and display anti-foreigner sentiment compared to identifiers with other parties. Interestingly, the majority of UKIP identifiers display traditional values (53 per cent), as do the majority of CON identifiers (55 per cent) and LAB identifiers (56 per cent).

In France (figure 12) we find that those who identify with the extreme right party Front National (FN) differ most starkly from their French counterparts when it comes to globalization. They are more likely to state that they are economically anxious, that globalization is a threat, and display traditional values. Interestingly though the majority of identifiers with the mainstream right and left (Rep and PS) can also be classified as traditionalists.

In Italy, a large majority of identifiers of the right wing parties Lega Nord (LN) and the populists Five Star Movement (MVCS) display a high level of economic anxiety and traditionalism (see figure 13). Party identifiers in Italy are not so fearful of globalization, with the exception of the LN, a majority of LN identifiers, namely 66 per cent view globalization as a threat. Identifiers across all parties are quite split in terms of traditionalism.

Figure 14 shows the globalization fears and traditional values among party identifiers in Poland. It is important to note that Poland does not have any left wing parties in Parliament. The party spectrum ranges from liberal conservatism to extreme right. However, we find substantial variation between party identifiers when it comes to globalization fears as we found in other countries thus far. While only a minority of liberal conservative PO and .Nowo identifiers think that globalization is a threat (34 and 23 per cent respectively), a majority of the right wing PiS and extreme right K’15 identifiers do (both with 58 per cent). Party identifiers agree much more in terms of traditionalism, only .Nowo identifiers are slightly less likely to display traditional values.

Figure 15 show that identifiers of the left wing challenger party Podemos especially differ from other identifiers based on their economic anxiety. 49 per cent of Podemos identifiers are economically anxious. When it comes to traditional values we find that Podemos identifiers display the lowest level (43 per cent), the identifiers of the left and right mainstream party, PP and PSOE, are similarly traditional (62 and 57 per cent respectively).

In Hungary, we also find substantial variation between party identifiers based on globalization fears. The extreme right party Jobbik and national conservative party Fidesz identifiers are most likely to report that they think globalization is a threat. Interestingly, with the exception of the green LMP identifiers, over 40 per cent of identifiers with other parties (the social democrat Magyar Szocialista Párt MSZP and the social conservatives Kereszténydemokrata Néppárt KDNP) display traditional values. (Figure 16)

Figure 17 displays the globalization fears and traditional values of party identifiers in the Netherlands. The levels of traditionalism are quite high among party identifiers, although the social-liberal D66 identifiers display the lowest level (38 per cent). Identifiers with the far right and far left party, PVV and SP, display comparatively high levels of economic anxiety (37 and 40 per cent respectively) and are much more likely to think that globalization constitutes a threat (57 and 45 per cent respectively. Fear of globalization is highest among those who identify with the far right (57 per cent think globalization is a threat).

Finally, among party identifiers in Austria we find stark differences between identifiers of the far right Freedom Party (FPÖ) but not in terms of their traditional values, but rather based on their globalization fears. 69 per cent of FPÖ identifiers think that globalization is a threat, while 52 per cent feel economically anxious. The level of traditionalism spreads from 19 per cent (Grüne) to 52 per cent (Neos). (Figure 18)

Our findings show that party identifiers in the nine countries differ primarily when it comes to their globalization fears. Especially parties on the extreme right seem to attract people who think globalization is a threat and are economically anxious. Traditional values are much more evenly split among parties on the extremes and centre (right).

What are People’s Specific Fears Regarding Globalization?

After having established that globalization fears seem to be associated with the starkest differences in what people want politically, we now turn to the question of what people exactly fear about globalization. We explore this by examining responses to a question asking what the biggest challenges facing the world in the coming decade are. When comparing the answers, we realise that most of the challenges we proposed — from war to environment to economic crisis to migration — are seen as equally important by those who fear globalization and by those who embrace it. Migration is the only major global challenge that is viewed differently by those who think globalization is an opportunity versus those who think it is a threat (Figure 19).

While a clear majority of those who fear globalization, namely 53 per cent, think migration is a major global challenge in the coming decades, 42 per cent of those who think globalization is an opportunity believe the same. This suggests that people who fear globalization seem to be motivated by concerns about migration. Interestingly, figures 20 and 21 suggest that those who are fearful of globalization have less contact with foreigners compared to those who think globalization is an opportunity (55 versus 43 per cent respectively), but at the same are more likely to feel like strangers in their own country 54 versus 36 per cent. Figure 22 displays how people feel about other major challenges. The share of people who think war is the main global challenge in the coming decades, split by globalization attitude, reveal there are not many differences between the two groups. 45 per cent of those who think globalization is a threat think that war is the main global challenge in the coming decades compared to 45 per cent of those who think globalization constitutes an opportunity.

We find a slightly larger difference between those who think globalization is a threat versus those who do not when it comes to the environment, but this difference is not huge (see Figure 22). While 42 per cent of those who fear globalization think the environment is the main global challenge, 47 per cent of those who think globalization constitutes an opportunity agree.

We find virtually no difference when it comes to opinions about poverty as a challenge between those who are fearful of globalization compared to those who are not (see Figure 22). 45 per cent of respondents who view globalization as a threat think poverty is the main challenge and 45 per cent of those who think globalization as an opportunity do.

When it comes to views about the extent to which economic crisis is a main global challenge we find little difference based on globalization fears. Figure 20 shows that 43 per cent of those who fear globalization view economic crisis as a major global challenge, while 45 per cent of those who think globalization constitutes an opportunity do.

When it comes to crime and terrorism, we also find virtually no differences based on globalization fears. Figure 22 shows that a little over 40 per cent of those who fear globalization versus those who think it constitutes an opportunity, think crime and terrorism are major challenges.

Concluding Remarks

Two possible explanations feature most prominently in the discourse about the origin of the populist vote. Some stress that progressive values have taken hold of the political mainstream and that talk about marriage for all, ethnic diversity and equal rights has gone too far for some citizens. These citizens turn to populist parties to restore order. Others emphasize the importance of globalization and its asymmetric economic consequences in the debate. In this study we put both explanations to the test, the results are unambiguous: In Europe, the main force behind the populist revolt are fears of globalization.

In contrast to the United States, where studies have shown a strong connection between a traditional authoritarian worldview and the support for the Tea Party or the Republican President-elect Donald Trump, in Europe values do not seem crucial for understanding why people turn toward populist parties. Certainly, there are as many Europeans with a traditional authoritarian worldview as there are people with a progressive liberal worldview. Here traditionalism, or also coined as authoritarianism in the political psychology literature, captures people’s desire for order and stability over flexibility and change. Traditionalists prefer strong leaders that preserve the status quo and impose order in a world they feel is under threat. 50 per cent of Europeans favour stability over flexibility, while 50 per cent favour flexibility over stability. Interestingly, this distribution is found almost equally in all social, political and national groups.

At first sight, people’s attitudes towards globalization do not differ much either. 45 per cent of Europeans feel that globalization is a threat whereas 55 per cent see it as an opportunity. But when we examine who is fearful or hopeful about globalization, and what they want politically, a stark contrast comes to the fore. The lower the level of education, the lower the income, and the older people are the more likely they are to see globalization as a threat. Moreover, those who feel close to populist parties are mainly motivated by fear of globalization. This effect is particularly evident when it comes to right wing populist parties, but it is also present for left wing populist parties. In Germany, 78 per cent of supporters of the right wing Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) fear globalization. In France, 76 per cent of Front National (FN) voters fear globalization. In Austria, 69 per cent of Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) supporters fear globalization. Economic anxiety also plays its part in the right wing success story, but to a lesser degree. Traditional values trail behind in third place.

Globalization of course is a multifaceted process. In the public discourse, it often represents fears about greedy bankers, migrants who use social services, or robots who make factory jobs obsolete. Our findings indicate that people who view globalization as a threat most strongly fear migration. They are more likely to see migration as a major challenge in the future, they are less likely to be in touch with foreigners in their daily lives, and more often express anti-foreigner sentiments. They also are more sceptical about the European Union and politics in general.

It seems fair to say that addressing these fears constitutes the key challenge for mainstream parties on the left and right. Only by addressing these fears could voters be won back from their populist challengers. Parties all over Europe seem to be realizing the need to adapt. Two different strategies seem to have emerged. Let’s call them the May and Merkel method. The May method consists of shifting political rhetoric. In her widely noted speech at the party convention in Birmingham in October 2016, May made statements that broke with the existing line of the Conservative Party. Here a few examples:

“It wasn’t the wealthy who made the biggest sacrifices after the financial crash, but ordinary, working class families. And if you’re one of those people who lost their job, who stayed in work but on reduced hours, took a pay cut as household bills rocketed, or someone who finds themselves out of work or on lower wages because of low-skilled immigration, life simply doesn’t seem fair. (…)

But if you believe you’re a citizen of the world, you’re a citizen of nowhere. You don’t understand what the very word ‘citizenship’ means. (…)

Because if you’re well off and comfortable, Britain is a different country and these concerns are not your concerns. It’s easy to dismiss them — easy to say that all you want from government is for it to get out of the way. But a change has got to come. It’s time to remember the good that government can do.”

Whether this change in rhetoric will be matched by a change in policy remains to be seen. Her shift in rhetoric is astounding because our findings suggest that Theresa May did not really speak to the Tory voter. The Tory voter today does not fear globalization nor does s/he feel economically anxious. Yet, the UKIP voter does, as does the Labour supporter albeit to a lesser degree. A change in rhetoric might be a risky move. We know from experiences in other countries and research that changes in rhetoric might foster changes in the political culture that may lead a life of their own. Playing with fears and resentments may be a powerful political tool, but it is prone to backfire. Recent history in neighbouring European countries teaches us that right wing populists hardly ever conquer government offices, and if they do only for a short time. Their true power lies in pushing the parties in government as far to the extremes as possible, dragging all the political field along.

The Merkel method on the other hand favours policy changes over changes in rhetoric. Political observers rightly point out that her shift in policies concerning the refugees has been significant since early 2016. The EU-Turkey deal has reduced the numbers of refugees arriving at the Greek coast. Also it has become more difficult for those who do arrive to reunite with their families. Family fathers for example who took up the peril counting on a generous program for family reunification see their hopes shuttered. The legal standards for asylum seekers may not have been lowered, but the conditions under which to live once asylum is granted have become tougher. Also, it has become harder to qualify as an asylum seeker. The current German government has significantly enlarged the number of countries classified as “sichere Drittstaaten”, which means that their nationals have almost no chance to even apply for asylum. They can be sent back without further enquiry if they cannot prove that they are under serious threat. These changes in policy need to be understood against the backdrop of a changing political environment. The year 2016 was marked by a fall in popularity of chancellor Merkel, by strong opposition to her politics from within her own political block and by the rise of the AfD, the right wing challenger party. It is part of the political conventional wisdom in Germany, that the conservative party union CDU/CSU has always seen it as their duty to secure the right wing fringes of politics in order to prevent any right wing populist to take the political stage ever again. The recipe to do so was: “Pursue your industry friendly economic policy but always keep a keen eye on social policy. Do not let the drift widen too much. Also, be friendly to asylum seekers. But be firm on migration.” The general impression is that Merkel broke that tradition with her refugee friendly policy and rhetoric in fall 2015. Now they are trying to put the genie back in the bottle. To do so, they make it less attractive to ask for asylum but they do not touch the right of asylum as such neither in action nor in rhetoric.

Yet this method brings with it the risk that the political effects that establish themselves are not the ones that were expected. Especially in the time of seemingly unlimited communications there is the need for pointed communication that can break through the flood of other messages and calm those that are concerned. Similar to the “your deposits are safe” speech that the German Chancellor along with the then finance minister Peer Steinbrück gave early in the financial crisis. The message then: “we will deal with this, everything is under control.” Such a gesture has yet to happen and as such the strange sentiment that “nothing has happened, politics is overwhelmed” seems to stick around. This impression is supported by the fierce infighting between the conservative party alliance (CDU and CSU) of the past few months. A reconciliation partnered with a concentrated communication directive that exudes “we are in control of the situation” would probably greatly harm the development of the AfD.

It is politically easier to turn the clock back on migration than it is to turn it back on economic issues. Governments who wish to tackle distribution issues or regulate technological advancement would face not only pressure from industries, but also a toxic combination of high social budgets, low public income, and an unfavourable demographic trend, which in turn, allow little room for manoeuvre.

Nevertheless it will be necessary to reconsider distribution of globalization gains in industrialised countries and develop compensatory and supportive measures for those who suffer most from negative effects. Education and training is key. Research shows that the higher the level of education the less likely people fall for populists claims.

Our data also shows that those with a low level of education and income tend to fear globalization the most. The same group of people is most vulnerable to the change that has occurred and will occur. Managing the risks that these people are exposed to will be key to appease the political situation in European countries.

References

Feldman, Stanley, and Karen Stenner (1997), ‘Perceived threat and authoritarianism’, Political Psychology, 18(4), p. 741–770.

Feldman, Stanley (2003), ‘Enforcing social conformity: A theory of authoritarianism’, Political Psychology, 24(1), p. 41–74.

Hetherington, Marc J., and Jonathan D. Weiler (2009), ‘Authoritarianism and polarization in American politics’, Cambridge University Press.

Inglehart, Ronald F., and Pippa Norris (2016), ‘Trump, Brexit, and the Rise of Populism: Economic Have-Nots and Cultural Backlash’, HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series, p. 16–026.

Rodrik, Dani (2011), ‘The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy’, Cambridge University Press.

Method

This report presents an overview of a study conducted by Dalia Research in August 2016 on public opinion across 28 EU Member States. The sample of n=14.993 was drawn across all 28 EU Member States, taking into account current population distributions with regard to age (14–65 years), gender and region/country. In order to obtain census representative results, the data were weighted based upon the most recent Eurostat statistics. The target weighting variables were age, gender, level of education (as defined by ISCED (2011) levels 0–2, 3–4, and 5–8), and degree of urbanization (rural and urban). An iterative algorithm was used to identify the optimal combination of weighting variables based on the sample composition within each country. An estimation of the overall design effect based on the distribution of weights was calculated at 1.54 at the global level. Calculated for a random sample of this size and considering the design-effect, the margin of error would be +/-1.1 per cent at a confidence level of 95 per cent.