As the May vote for the European Parliament (EP) nears, immigration is likely to be widely debated on the campaign trail. After all, the issue was at the heart of the 2016 referendum on Brexit, as well as a number of more recent national elections. Also, since 2015 large numbers of migrants, notably Syrians, have arrived at the EU’s southern border. This has caused tensions between member states with Italy blaming its northern neighbours for lack of solidarity. Eastern and central European governments refuse to welcome asylum seekers and Schengen internal borders were re-established in countries including France and Sweden. These are all signs of “Europe’s crisis” and the EU’s inability to agree upon common policy solutions.

Since 2015, the EU has deployed ever more means to interdict arrivals, such as the FRONTEX agency military operations on the EU’s southern borders. With targeted funds for border management, it has also enlisted transit and origin countries to prevent migrants from reaching EU territory: for example, €6 billion for the EU-Turkey agreement and the €4 billion of EU emergency funds for Africa. Even a media-savvy EU citizen would not know about these navy operations or transfers of funds.

The EP has been united in pushing forward reform of the Common European Asylum Policy, but the institution has been bypassed or the Council of Ministers has blocked negotiations. Again, only “EU nerds” follow these developments. As in many other policy domains, there is a paradox: political leaders say there is a crisis, yet little is communicated about EU responses. In brief, the citizens voting on May 2019 are told by political parties and the media that immigration is a key issue -- but they know little about EU policy.

What do EU citizens think about immigration?[1] There are quite a few surveys that allow for cross-national studies on immigration and, to some extent, longitudinal analyses that help identify the sociodemographic characteristics of persons holding a particular opinion. In many polls, it is unclear what respondents understand by “immigrants” or “immigration”. For instance, who do they have in mind when a Gallup poll asked: “Should immigration in this country be kept at its present level, increased or decreased?” We have to take for granted that people have different mental maps. So perhaps one issue is precisely how people perceive this phenomenon and what they know about it.

In a recent post on this blog, Claes de Vrees underlined that media coverage will be crucial during the EP campaign. As we know, misinformation spreads far more quickly than verified news stories.[2] Rumours about immigration are no exception as shown recently when both far right parties and social media contended that the UN Global Pact on Migration would create a “right to immigrate” and hundreds of millions Africans would move to Europe, which led the Belgian government to fall in December 2018. [3]

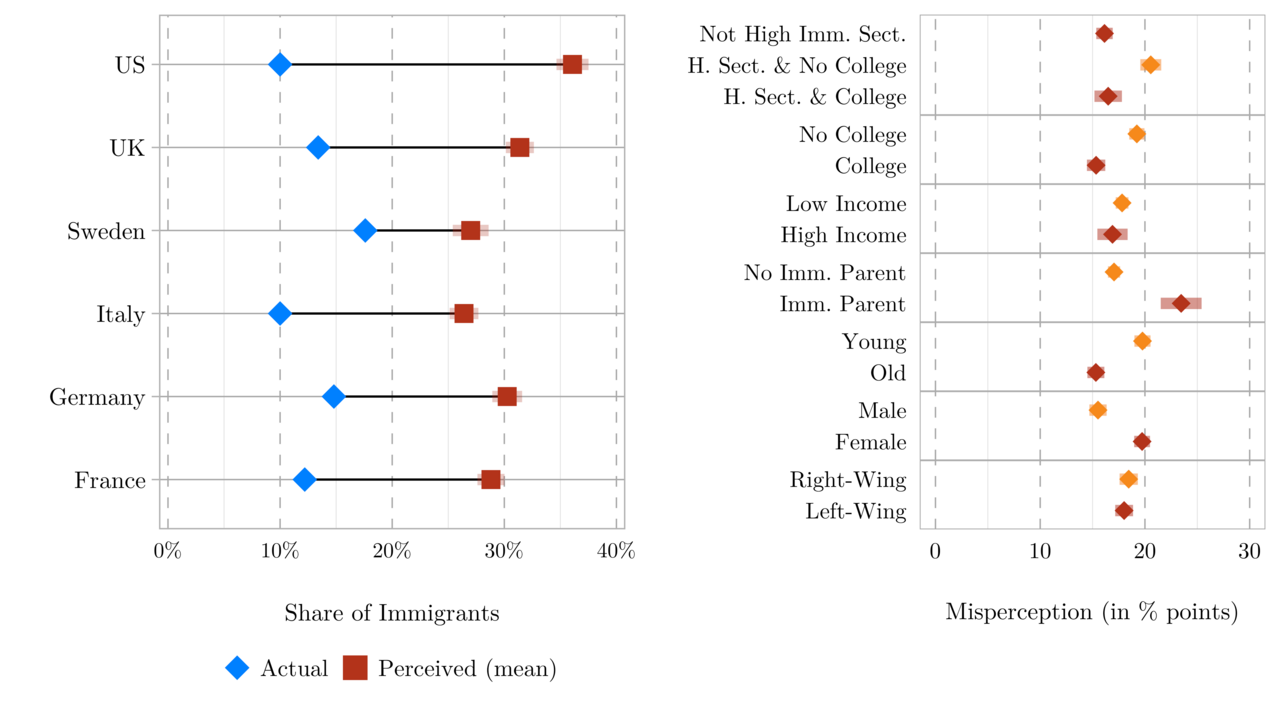

One reason this will be a challenge is that we have robust data on the high level of misperceptions that European citizens have about immigrants. We have known for a long time that negative attitudes towards migrants are based on a perceived group threat that doesn’t correspond to the size of the foreign population and depends in part on their economic position of their group vis à vis others.[4] Misperceptions about migration are widely spread. Based on a survey on a representative sample of around 22,500 respondents from the U.S. and five European countries (France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, U.K.), Alberto Alesina, Armando Miano and Stefanie Stantcheva found that, in all cases, all respondents “greatly overestimate the total number of immigrants, think immigrants are culturally and religiously more distant from them, and are economically weaker – less educated, more unemployed, poorer, and more reliant on government transfers – than is the case.”[5]

Another aspect of opinion on immigration relevant to the EP election is polarization: publics are divided and tend to embrace extremes, which the 2014 European Social Survey[6] revealed. Compared to 2002, results show that within-country divisions are on the rise: an increased proportion felt that no migrants from non-EU poor countries should come, yet more persons felt that precisely such migrats should be allowed entry: there are fewer people with no opinion or who feel that the situation should stay the same.[7] Parties outside the mainstream right and left usually do well in EP elections and also those with strong views on immigration and the EU, such as the Greens and the far right. These surveys give them no incentive to tone down their stances.

Opinions are thus polarized, based on misperceptions and a lack of knowledge of migrants and migration as a social phenomenon. According to scholars of populism such as Tim Bale and Sheri Berman, mainstream parties that have tried to capture the anti-immigrant vote or ignore it in unsuccessful ways are in part responsible for this situation. This is the year that they should stop, at the very least, to contributing to misinformation on immigration.

Immigration: perceived vs. actual numbers

Source: Alberto Alesina, Armando Miano, and Stefanie Stantcheva, “Immigration and Redistribution,” NBER Working Paper 24733. June 2018.

Another aspect of opinion on immigration relevant to the EP election is polarization: publics are divided and tend to embrace extremes, which the 2014 European Social Survey[6] revealed. Compared to 2002, results show that within-country divisions are on the rise: an increased proportion felt that no migrants from non-EU poor countries should come, yet more persons felt that precisely such migrats should be allowed entry: there are fewer people with no opinion or who feel that the situation should stay the same.[7] Parties outside the mainstream right and left usually do well in EP elections and also those with strong views on immigration and the EU, such as the Greens and the far right. These surveys give them no incentive to tone down their stances.

Opinions are thus polarized, based on misperceptions and a lack of knowledge of migrants and migration as a social phenomenon. According to scholars of populism such as Tim Bale and Sheri Berman, mainstream parties that have tried to capture the anti-immigrant vote or ignore it in unsuccessful ways are in part responsible for this situation. This is the year that they should stop, at the very least, to contributing to misinformation on immigration.

[1] Caveat: EP elections have a very low turnout, EU “free movers” vote very little, citizens with anti-migrant opinions are among the socioeconomic categories that also are likely to abstain from voting. Issue salience varies so data on EU opinions is not a predictor for the vote.

[2] Soroush Vosoughi, Deb Roy, Sinan Aral, “The spread of true and false news online,” Science 09 March 2018: 1146-1151.

[3] Reactions on social media to the picture of Aylan Kurdi a young boy dead on a Turkish beach in September 2015 shows the predominance of emotional and conspirationist posts. Mette Mortensen, and Hans-Jörg Trenz (eds), Global moral spectatorship in the age of social media. London: Routledge, 2016.

[4] See the seminal multi-level analysis of EU-12 population data and Eubarometer data: Lincoln Quillian, “Prejudice as a Response to Perceived Group Threat: Population Composition and Anti-Immigrant and Racial Prejudice in Europe,” American Sociological Review 60(4): 586-611.

[5] Alberto Alesina, Armando Miano, and Stefanie Stantcheva, “Immigration and Redistribution,” NBER Working Paper 24733. June 2018 (revised July 2018), p. 1.

[6] Anthony Heath and Lindsay Richards, Attitudes towards Immigration and their Antecedents Topline Results from Round 7 of the European Social Survey, November 2016. URL: www.europeansocialsurvey.org/docs/findings/ESS7_toplines_issue_7_immigration.pdf

[7] The socioeconomic characteristics that are relevant (education, age and income in that order) are also significant for predicting support or lack thereof for the EU.