Executive Summary

Last year we published the report Fear Not Values: Public opinion and the populist vote in Europe in which we presented survey evidence suggesting that supporters of populist parties differ from supporters of mainstream parties in one important respect: they fear globalization.

Here we follow up on these findings and explore in depth people’s knowledge and feelings about globalization and how these are linked to their views about the future of the European Project. We present evidence based on a survey conducted in July 2017 in which we asked over 10,000 EU citizens in every member state about their globalization fears and their opinions about future European cooperation. We present two sets of evidence; one is based on a sample capturing public opinion in the EU27, and the other amplifies the picture by focusing more in-depth on respondents from the five largest member states in terms of population, France, Germany, Italy, Poland and Spain. Since our report focuses on future European cooperation post-Brexit, we focus on the EU27 only and have excluded Great Britain.

- A considerable number of Europeans think globalization is a threat (44 per cent EU-wide). But when probed about their personal experiences with globalization these have overall been more often good than bad (66 per cent of Europeans consider that globalization has been good or more good than bad personally). The supporters of populist parties are an exception: they are both fearful of globalization and have had bad personal experiences with it. (63 per cent of AfD supporters consider globalization a threat while 56 per cent say it has been bad or more bad than good for them personally; 81 per cent of FN supporters see a general threat while 60 per cent see a personal disadvantage.)

- Europeans share a common understanding of what they think the globalization process means: they associate it with trade (increased movement of products for 19 per cent and money for 17 per cent) and migration (increased movement of people for 17 per cent). This result is quite stable in a wide variety of subgroups be they national, socio-economic, political.

- While those who are optimistic about globalization also welcome more European cooperation (64 per cent), those who fear it hold much more heterogeneous views (45 per cent of them are in favor of more political and economic integration, but 41 per cent want less of it). Almost half of those who fear globalization see European cooperation as part of the solution for addressing these fears. Generally speaking, the threat camp is politically more heterogeneous than the opportunity camp. This pattern holds true in all member states although in France those frightened by globalization tend to favor less integration (53 per cent), while only 34 per cent wish for more. In Spain and Italy, the fear camp on the other hand wishes for more integration (68 per cent and 56 per cent more respectively, 26 per cent and 38 per cent less).

- Populist left-wing party supporters think globalization is a threat, but want more European cooperation. In fact, in some areas, such as acceptance of migrants and protecting the rights of EU migrants, they wish to go further than the average EU27 citizen. For populist right-wing party supporters, the EU is seen as part of the problem and fuels their globalization fears. They wish to see less European cooperation in future.

- Despite these differences, the vast majority of respondents from the EU27 agree in one key respect: they want the EU to focus its future efforts on the fight against terrorism and the management of migration. Economic issues have lost importance in the minds of Europeans. This result is pretty constant across a wide variety of subgroups - national, socio-economic, and/or political.

Introduction

In November 2016 we published the report Fear Not Values: Public opinion and the populist vote in Europe [1] in which we presented survey evidence suggesting that supporters of populist parties differ from supporters of mainstream parties in one important respect: they fear globalization. Populist party [2] supporters are more anxious about their economic position and view globalization as a threat. What’s more, they retain a deep scepticism towards the ruling elite. What they, especially voters favoring the far right, are most concerned about is migration. Interestingly, however, they admit having little or no direct contact with migrants in their everyday lives. Fears about globalization and what the process might bring in the future seems a key concern for populist party supporters. Figure 1.1 and 1.2 summarize some of the key findings of our previous report.

While many commentators expected such globalization fears to shift a series of electoral contests in a more populist direction, the outcomes of the Dutch, French and German elections did not directly echo the electoral success of populist messages that had paved the way for Brexit and the election of US President Donald Trump. Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte fought off the challenge of the populist right-wing political entrepreneur Geert Wilders, Emmanuel Macron beat the far-right presidential candidate Marine Le Pen in France, and German Chancellor Angela Merkel was re-elected for a fourth term, even though the Alternative for Germany made considerable electoral gains. These recent election results together with persistent signs of economic recovery led Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker to spell out an optimistic view for Europe’s future in his 2017 State of the Union address. He argued that “the wind is back in Europe’s sails. Let us make the most of the momentum” by using this “window of opportunity.”[3]

While the outcome of the Brexit vote and the US presidential elections may have made many observers of European politics too gloomy, the recent election outcomes may have swung them towards over-optimism. Some commentators suggest that the populist tide has turned.[4] In this report, we wish to urge caution. Observers of European politics should not lull themselves into the belief that the recent election outcomes somehow suggest that people’s grievances and discontent with the mainstream are a thing of the past. While a window of opportunity to shape Europe’s future post-Brexit might exist, national and European elites should tread this territory carefully. It cannot simply be politics as usual.

In this report we explore people’s fears about globalization and how these are linked to their views about the future of the European Project. We present evidence based on a survey conducted in July 2017 in which we asked over 10,000 EU citizens about their perception of globalization and their opinions about future European cooperation. We present two sets of evidence: one based on a sample capturing public opinion in the EU27, and the other completing the picture by focusing more in-depth on respondents from the five largest member states in terms of population, France, Germany, Italy, Poland and Spain. Since our report focuses on future European cooperation post-Brexit, we focus on the EU27 only and have excluded Great Britain. Specifically, we seek to answer four questions:

- How do people evaluate the process of globalization, and what does it mean to them?

- Are people who are fearful of globalization also skeptical about political and economic cooperation within the EU?

- What do people who are fearful of globalization want from the EU?

- How do opinions about globalization and political and economic cooperation?

- What do people who are fearful of globalization want from the EU?

- How do opinions about globalization and political and economic cooperation within the EU differ among supporters of mainstream versus supporters of populist left- and right-wing political parties?

There are five main takeaways from our data:

- A substantial proportion of Europeans think globalization is a threat, but when probed about their personal experiences with it they report that these have overall been more good than bad. The supporters of populist parties are the exception here. They are both fearful of globalization and have had bad personal experiences with it.

- Europeans share a common understanding of what they think the globalization process means: they associate globalization with trade (increased movement of products and money) and migration (increased movement of people).

- While optimists about globalization also welcome more European cooperation, those who are more fearful hold much more heterogeneous views. For some citizens who are fearful of globalization, European cooperation is seen as part of the solution for addressing these fears.

- Populist left-wing party supporters think globalization is a threat, but want more European cooperation. In fact, in some areas, such as acceptance of migrants and protecting the rights of EU migrants, they wish to go further than the average EU27 citizen. For populist right-wing party supporters, the EU is seen as part of the problem and fuels their globalization fears. They wish to see less European cooperation in future.

- Despite these differences, the vast majority of respondents from the EU27 agree in one key respect: they want the EU to focus its future efforts on the fight against terrorism and the management of migration.

Our report consists of four parts. In the first, we explore people’s fears about globalization. What does globalization mean, do people view it as a threat, and how do they evaluate its consequences for them personally? Here we explore differences across countries and party supporters. In the second part, we examine what those who are fearful of globalization think about European integration compared to those who are optimistic. Should European cooperation go further or should it come to a halt? Again, we touch on differences across countries and party supporters. The third part explores what people want from the EU in future. What should the EU’s future policy priorities be? Here we explore differences between those who fear globalization and those who do not as well as across countries and party supporters. In the fourth and final part, we draw some conclusions and outline some of the challenges and constraints that elites might face when shaping European cooperation in the coming years.

[1] https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/de/publikationen/publikation/did/fear-not-values/.

[2] Note that many different definitions of populism exist in the literature (see Mudde and Kaltwasser 2013 or Guiso et al. 2017). In most definitions the mobilization of anti-elitist views is key.

[3]Globalization and the EU: Threat or opportunity? For the full transcript of the speech, see http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-17-3165_en.htm.

[4] See for example https://www.ft.com/content/b0f45f12-e7c8-11e6-967b-c88452263daf, https://www.forbes.com/sites/lbsbusinessstrategyreview/2017/06/05/french-lessons-how-emmanuel-macron-is-turning-the-tide-on-populism/#238f61c115d4, or http://en.rfi.fr/france/20170508-macron-win-may-show-populist-tide-turning.

What do people think about globalization?

In Focus

Getting a clear sense of how people evaluate globalization is not an easy task. This is mainly due to the fact that no established tradition exists. In this report, we rely on people’s responses to a series of different survey questions designed to tap into what globalization means to them, and how they evaluate the process. In order to get a sense of what ‘globalization’ means to people we rely on the following survey question:

- The word “globalization” is often used today to describe a world that is increasingly interconnected. If you had to choose from the list below, which best describes what the word mean to you?

- The increasing movement of products

- The increasing movement of ideas

- The increasing movement of money

- The increasing movement of jobs

- The increasing movement of people

- The increasing connectedness of culture

- The increasing connectedness of technology[1]

- Please pick 3 in order of importance.

Figure 2 shows the percentage of people who associate ‘globalization’ with the increased movement of products, ideas, money, jobs, people or the growing connectedness of culture or technology respectively within the EU27. Across the EU27 more people associate it with the increasing movement of products than with anything else: 19 per cent of respondents. The second equal most important association with ‘globalization’ is the movement of money (17 per cent) and that of people (17 per cent). Only 10 per cent of respondents associate it with the increased movement of jobs.

Figure 3 explores differences among the five most populous EU member states. In all five countries examined, we find that ‘globalization’ is most often associated with the increasing movement of products, money and people. In most of these countries people associate ‘globalization’ with the movement of goods, with the exception of Poland and Italy where ‘globalization’ is equally strongly associated with the movement of people.

As mentioned in the introduction, in our previous report Fear Not Values: Public opinion and the populist vote in Europe, we have shown that supporters of populist parties are particularly worried about globalization. Hence, we next examine if supporters of populist and mainstream parties or those who are not close to any party differ when it comes to what they think globalization is all about. Here we rely on more in-depth surveys conducted in France, Germany, Italy, Poland and Spain in which we asked respondents which political party they felt closest to. Figures 4.1, 4.2, 4.3, 4.4 and 4.5 display the meanings of globalization among party supporters in these five countries.

The numbers suggests that interesting variations exist across different party supporters when it comes to meanings of ‘globalization’. For example, supporters of the right-wing Les Républicains (LR) in France, Forza D’Italia (FI) in Italy or the Law and Justice (PiS) party in Poland associate the word globalization mostly with the increased movement of people. The same holds true for supporters of the Social Democratic party (PSOE) in Spain or the Left party (La France Insoumise [FI]) in France. Moreover, supporters of Liberal parties in Germany and Spain (FDP and Ciudadanos or C’s) are most likely to think that the word globalization refers to the increased movement of technology or ideas respectively. On the whole, however, party supporters and non-partisans mainly associate the word with the movement of money and products. Taken together, the results presented in figures 2-4 so far suggest that most respondents in the EU27 associate ‘globalization’ with both economic interconnectedness as in a focus on products and money (trade) or increased movement of people (migration).

Next, we examine how people evaluate globalization. We do so by relying on respondents’ answers to two survey questions. One taps into the extent to which people think that globalization constitutes a threat or opportunity, while the second asks respondents to evaluate how they feel affected by the process as a person.

- Do you think that globalization is an opportunity or a threat? Please select one.

- Globalization is often associated with a global economy that produces cheaper consumer goods (fashion, electronics etc), cheaper services (mobile communications, flights etc) and cheaper labour. For you personally, has globalization been:

- bad,

- more bad than good,

- more good than bad,

- good.

Figure 5 displays the proportion of people who feel that globalization constitutes a threat rather than an opportunity. Within the EU27 most people are optimistic about the globalization process, with 56 per cent viewing it as an opportunity. That said, however, 44 per cent are fearful, seeing it as a threat. The figure also shows that differences exist among the five largest member states. While a majority of German, Italian and Spanish respondents view globalization as an opportunity, 51 and 53 per cent of French and Polish respondents respectively think it constitutes a threat.

Do we find differences between populist and mainstream party supporters when it comes to fears about globalization? Figures 6.1, 6.2, 6.3, 6.4 and 6.5 suggest that the answer is yes. They show the proportion of respondents who think that globalization constitutes a threat or opportunity among party supporters and non-partisans in the five most populous member states.

These figures show that the proportion of those stating that globalization is a threat is most pronounced among supporters of populist right-wing parties. For example, 81 per cent of National Front (FN) supporters in France think it a threat, as do 63 per cent of Alternative for Germany (AfD), 60 per cent of Law and Justice (PiS) supporters in Poland, and 56 per cent of Lega Nord (LN) supporters in Italy. Globalization fears are slightly less pronounced among populist left-wing party supporters. While a majority of Podemos supporters in Spain for example thinks globalization is an opportunity, 52 and 51 per cent of supporters of the Left party (La France Insoumise [FI]) in France and in Germany (Linke) respectively think it is a threat. Party supporters of mainstream parties on average think that globalization constitutes an opportunity. Support is most pronounced among supporters of Emmanuel Macron’s party in France (LaREM), the Social Democratic party in Italy (PD) and the Popular Party (PP) in Spain, all at over 80 per cent.

The findings presented in figures 5 and 6.1–6.5 suggest that large numbers feel threatened by globalization, especially among those who support populist right-wing parties. Now, we examine how people feel about the personal impact of globalization upon them. Respondents could give clearly positive or negative responses (globalization has been bad/good for me personally) or more nuanced ones (globalization has been more bad than good /more good than bad for me personally). Figure 7 shows that within the EU27 as well as across the five largest member states, the largest proportion of respondents is mildly positively disposed towards globalization and thinks that on average it has been more good than bad for them personally: 52 per cent of respondents in the EU27. The majority of French, German, Polish and Spanish respondents think the same. In Italy, however, views are much more divided: 42 per cent think that globalization has been more good than bad for them personally, while 38 per cent think it has been more bad than good. While considerable numbers of Europeans think globalization is a threat, when they are probed about their personal experiences they report that these have overall been more good than bad. The supporters of populist parties are the exception here. Most are both fearful of globalization and report having had bad personal experiences with it.

Figures 8.1, 8.2, 8.3, 8.4 and 8.5 inspect differences among party supporters in the five largest member states. Interestingly, the pattern between populist right- or leftwing party supporters and mainstream party supporters is much less pronounced than was the case for globalization fears. While a clear majority of supporters of the populist right think that globalization constitutes a threat, not all of them feel that the process has been bad for them personally. The largest proportion of Alternative for Germany (AfD) and National Front (FN) supporters state that globalization has been more bad than good for them personally (47 per cent) while 43 per cent of Lega Nord (LN) supporters do. The largest proportion (48 percent) of Italian party supporters for whom the personal consequences of globalization have been more bad than good identifies with the Five Star Movement (MVCS). On the left, 46 per cent of party supporters of the left-wing party La France Insoumise (FI) think globalization has been more bad than good, as do 38 per cent of Podemos (Podemos) supporters. The majority of mainstream party supporters view the personal consequences of globalization as more good than bad.

Overall, the results thus far suggest that the movements of money, products and people are the commonest associations that people make with ‘globalization’. This in turn suggests that people’s understanding of globalization dovetails with the academic debate about the roots of the current backlash against it. This highlights both economic reasons and worries about migration (see Funke et al. 2016 and Norris and Inglehart 2016 for example). Interpretations are very similar across countries, but do differ across party supporters. Although the majority of Europeans are on average more optimistic than pessimistic about globalization, albeit mildly so, a substantial part of Europe’s population is worried about it. These fears are most pronounced among populist right-wing party supporters, less so among populist left-wing party supporters.

Supporters of mainstream parties view globalization more as an opportunity than threat, and feel that the process on average has had more positive than negative consequences for them personally.

[1] The order of the answer categories were randomized.

Are people who fear globalization also sceptical about EU integration?

Now we examine what those who believe globalization to be a threat versus those who view it as an opportunity think about the EU. In figure 9, we pit the support for further political and economic integration of those respondents who are fearful of globalization against the views of the relative optimists. We distinguish respondents according to their answers to the survey question that asked them if they think globalization constitutes a threat or opportunity. Then, we examine whether those who think globalization is a threat versus an opportunity want more, less or the same level of political and economic integration in Europe. Figure 9 suggests that the relationship between people’s views about globalization and their opinions about more political and economic integration in Europe is not that straightforward. While 64 per cent of respondents who view globalization as an opportunity also wish to see more political and economic integration, those who view it as a threat are much more divided: 45 per cent of those who are fearful of globalization want more integration, while 14 per cent want to keep the status quo and 41 per cent want less integration.

Figure 10 presents similar information to that shown in figure 9, but now broken down for the five largest member states. Interesting national patterns seem to emerge. Among French and German respondents who think that globalization is a threat, the largest proportion also wants less political and economic integration within Europe at 53 and 44 per cent respectively. This is not, however, the case for Italian, Polish and Spanish respondents. They always want to see more political and economic integration in Europe regardless of their stances on globalization. Support for more integration is unsurprisingly still more pronounced among those who think globalization is an opportunity compared to those who are skeptical about it.

How do populist versus mainstream party supporters view further political and economic integration in Europe? We know that above all supporters of populist left- and right-wing parties are wary of globalization but does this also translate into less support for European integration?

Figures 11.1, 11.2, 11.3, 11.4 and 11.5 point to some interesting results. A clear majority (64 percent) of National Front (FN) party supporters in France wish to see less political and economic integration followed by 59 per cent of Alternative for Germany (AfD) party supporters and in Poland 54 per cent of Kukiz’15 party supporters (K’15). Both party supporters and those who do not support any party in Italy and Spain want more integration. This is also the case for most supporters of mainstream parties in Germany, France and Poland. Interestingly, supporters of populist left-wing parties wish to see more integration in Europe. 62 and 47 per cent of party supporters of the Left party in Germany (Linke) and France (La France Insoumise [FI]) respectively wish to see more integration, a view shared by as much as 75 per cent of Podemos voters.

The findings presented in figures 9-11 suggest that globalization fears do not automatically translate into a more skeptical view about European integration. While those who think globalization constitutes an opportunity are also strongly back the prospect of further integration, those who see it as a threat are much more divided. Further examination of the results suggests that this is likely due to a left-right split on integration. For supporters of populist left-wing parties more Europe seems to be part of the answer to addressing their globalization fears, while for supporters of populist right parties the EU is part of the problem. These results lend support to the notion that the Left and its supporters may speak up against the EU but ultimately they wish to see it reformed, whereas many populist right-wing parties simply wish to leave the EU altogether (de Vries 2018).

What kind of European cooperation do people who fear globalization want in the future?

We have seen that globalization fears do not necessarily translate into more opposition towards European integration but now we wish to examine what those who are fearful of globalization and those who are more uncertain want from the EU in future. Here we focus on two aspects. We explore people’s views about

- the tasks the EU should focus on, and

- the kind of European cooperation respondents think their country should join in.

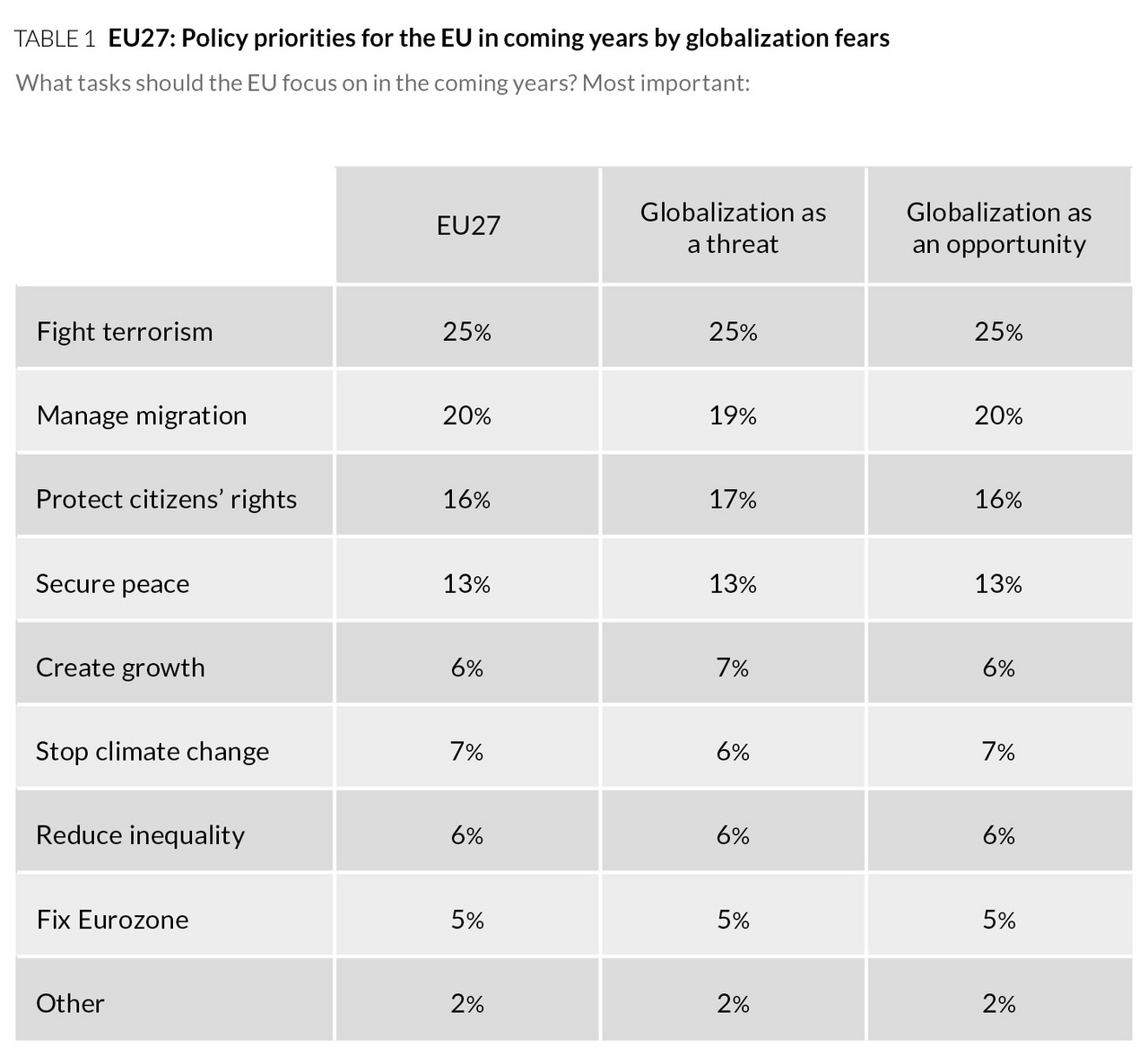

We begin with the first. What tasks do people want the EU to focus on in years to come? And how do the preferences of those who fear globalization versus those who do not differ on this topic? Table 1 gives the survey evidence on the first question:

- Fight terrorism

- Manage migration

- Protect citizens’ rights

- Secure peace

- Create growth

- Stop climate change

- Reduce inequality

- Fix Eurozone

- Other

It provides an overview of the proportion of respondents who think that a particular task should be the EU’s top priority in years to come. It also divides this information according to people’s globalization fears. Overall, the largest number of EU27 nationals think that the main task ahead is the fight against terrorism at 25 per cent, followed by managing migration at 20 percent, and protecting citizens’ rights at 16 per cent. Interestingly, this closer look shows up modest differences based on people’s globalization fears. Both sets of respondents think that the EU should focus on the same three key issues. Interestingly, most EU27 citizens do not view economic issues, such as growth, inequality and fixing the Eurozone, as the most important policy priorities in years to come. Fixing the Eurozone is indeed seen overall as the least important future task for the EU, with reducing inequality only slightly more so.

Do we find differences between countries? They do but figure 12 shows that the overall top three priorities - fight against terrorism, management of migration and protecting citizens’ rights - remain pretty much the same. Most of the public thinks that the main task for the EU to focus on is the fight against terrorism. This is a top concern for as many as 27 and 29 per cent of Italian and Polish respondents while for others it is securing peace. For example, 17 per cent of Polish and 15 per cent of Italian respondents who think globalization constitutes an opportunity think the EU should focus mainly on securing peace. Again, only very few think that fixing the Eurozone should be the EU’s main task in years to come. Overall, these findings suggest that peace and security issues related to terrorism are uppermost in the minds of many Europeans regardless of how they evaluate the process of globalization.

What do the different party supporters think the EU’s priorities should be in future? Figures 13.1, 13.2, 13.3, 13.4 and 13.5 suggest they mainly agree the top priority should be the fight against terrorism. The management of migration is on average the second most important policy priority. For supporters of the Alternative for Germany (AfD), the Liberal party in Germany (FDP), the National Front (FN) and Socialist party (PS) in France and of Kukiz’15 (K’15) in Poland the management of migration is even seen as the top policy priority.

Secondly, we examine the type of European cooperation people wish to see in future. We use four survey questions to tap into people’s preferences about the kind of European cooperation they think their country should contribute to in years to come. These include:

- To what extent do you think that [your country] should provide financial aid to another EU Member State facing severe economic problems?

- Answers from 1 ‘should not allow them in’ to 10 ‘should allow them in’.

- To what extent do you think [your country] should allow people to come and live here who are fleeing from political or religious persecution in line with EU quotas?

- Answers from 1 ‘should not allow them in’ to 10 ‘should allow them in’.

- To what extent do you think that [your country] should try to limit the rights of EU citizens to work and live here?

- Answers from 1 ‘should try to limit rights’ to 10 ‘should not try to limit rights’.

Table 2 provides an EU27 overview of views. The second column summarizes the views of the average EU27 respondent, while the third and fourth columns divides views on European cooperation between those who view globalization as a threat and those who view it as an opportunity. Higher answer categories reflect more support for European cooperation. Overall, people’s support for it is mildly positive. Respondents overall wish their country to contribute slightly more to EU policy initiatives in future. Although such support is not overwhelming, responses are close to 6 on a rising scale from 1 to 10. The least popular area of European cooperation is providing financial assistance to struggling member states at 5.3, while the most popular is the protection of EU migrant rights at 5.9 – though these differences in support are slight. Respondents who view globalization as an opportunity are more positively disposed towards European cooperation than the average EU27 citizen, while those who view it as a threat are on average more skeptical.

On a scale from 1 –10, my country should: Interestingly, both those who view globalization as an opportunity and/or a threat think that their country should respect the rights of EU member states to work and live in their country (6.4 and 5.4 respectively). Yet, while those who view globalization positively think their country should respect the rights of both EU migrants and refugees, pessimists about globalization are wary of accepting refugees in accordance with EU quotas (6.2 versus 4.8 respectively). Differences between those who fear globalization versus those who do not can also be found in views about establishing a European army. Those who think that globalization is an opportunity are of the view that their country should help more compared to those who fear globalization (6.2 versus 5.2). The final interesting thing to note in Table 2 is that support for financial assistance of a struggling member state finds the least support of all aspects of European cooperation regardless of respondents’ views about globalization (4.6 for those who see globalization as a threat and 5.7 for those who view it as an opportunity).

Figure 14 presents the same information as Table 2, but now divides it by the five largest EU27 member states. Although we find differences in the extent of support for European cooperation across countries, the pattern found in Table 2 based on globalization fears persists. The figure shows that overall those who fear globalization are least supportive of their country cooperating at the EU level, while those for whom it constitutes an opportunity wish to see more joint action.

Yet, the aspects of European cooperation that are least supported by those who fear globalization vary per country. In Poland refugee support is least popular among these, in Spain it is contributing to a European army, while in France, Germany and Italy providing financial support for struggling member states seems to be the biggest stumbling block. Among optimists about globalization, support for a European army is most popular in France, Italy and Poland, while in Spain it is support for the rights of EU migrants and in Germany the acceptance of refugees.

Figures 15.1, 15.2, 15.3, 15.4 and 15.5 display the support for European cooperation across different groups of party supporters in the five largest countries. The first thing to note is that among supporters of the populist right, European cooperation is eyed very skeptically, especially when it concerns providing financial assistance to struggling member states or the acceptance of refugees in line with EU quota. For example, supporters of the Alternative for Germany (AfD), National Front (FN), Forza D’Italia (FI), Lega Nord (LN) and/or Law and Justice (PiS) all provide a score below 5. Interestingly, the protection of the rights of EU migrants commands greater support among populist right-wing party supporters. In fact, only those of the National Front (FN) in France and Forza D’Italia (FI) in Italy give it a score below 5. Among populist left-wing party supporters, those of the Left party in Germany (Linke) or Podemos (Podemos) in Spain are quite skeptical of more military cooperation.

While security concerns should be high on the EU’s agenda according to them, the establishment of an European army is not perceived as the way forward to dealing with such concerns. Interestingly, support for helping to set up a European army is highest among party supporters in Poland. Party supporters of the German Left Party (Linke) and Spanish Podemos (Podemos) are also less positive about providing financial aid. Providing financial aid to member states in need is also least popular among mainstream party supporters, who are otherwise quite keen on more European cooperation in future.

The results in this section suggest that clear differences in people’s support for cooperation exist among those who fear globalization versus those who do not. We also find differences between those who support mainstream parties and those who support populist parties, especially on the right. Cooperation at the EU level in concert with other member states is least popular among those who view globalization as a threat and support populist parties on the right.

These respondents have overall little faith in European cooperation. Supporters of populist left-wing parties, however, do favor more European cooperation in future even though they share the same skepticism towards globalization as populist right-wing supporters. In fact, supporters of the populist left are often more supportive of European cooperation than the average European citizen. The clear exception to this is the creation of a European army that finds little backing.

When it comes to EU policy priorities in years to come we find fewer differences between the opinions of those who fear globalization and those who do not, or between populist and mainstream party supporters. Most respondents view the fight against terrorism and the management of migration as the key tasks ahead. Interestingly, economic policy focused on creating growth, fighting inequality or fixing the Eurozone are not perceived as top policy priorities. These results suggest that although differences between those who fear globalization and those who do not and between supporters of populist and mainstream parties exist, these groups share some political views. They want the EU to help in the fight against terrorism and to help provide security.

Although they differ on how much European cooperation they think is preferable, this is primarily due to the dissenting views of supporters of populist right-wing parties rather than on supporters of the populist left. That said, supporters of populist right-wing parties do share some views held by other groups. Especially when it comes to what the policy priorities of the EU should be in years to come: the fight against terrorism, management of migration and protection of citizens’ rights.

These policy priorities could provide useful starting points for policy makers. It would allow them to focus on the issues that bind rather than divide Europeans. Finding ways to deal with these challenges will be difficult and different groups might disagree about how best to tackle them, but they are now the most salient for almost every European citizen.

Concluding Remarks

The data summarized in this report conveys five keys messages about people’s fears and preferences for European integration.

- Europeans are split when it comes to their views about globalization. While significant numbers view globalization as a threat, when asked about their personal experiences with it they are on average positive. The pattern among supporters of populist parties is different. They report being both fearful of globalization and asserting that they have been badly affected personally.

- When it comes to the meanings that Europeans attach to the globalization process, we find many commonalities. The majority associates globalization with trade (increased movement of products and money) and migration (increased movement of people).

- We do not find a clear-cut relationship between people’s views about globalization and European integration. While optimists about globalization also welcome more European integration, those who fear it hold widely different views. Some of them support further integration. Some of them reject it.

- There seems to be an important difference between those who support populist left- and populist right-wing parties. While both sets think globalization is a threat, populist left supporters want more European cooperation and populist right ones do not.

- Despite these important differences, we find that the majority of Europeans do agree on two key issues: they want the EU to focus its future efforts both on the fight against terrorism and the management of migration.

What do these results mean for policy makers? In public discourse, globalization is often discussed in a variety of ways, for example as facilitating the rise of greedy bankers, migrants who abuse social services, or robots that make factory jobs obsolete. But also as producing cheap and convenient consumer goods and services. Our findings indicate that ordinary Europeans think of globalization in terms of increased movement of products and money (trade) and people (migration). This makes globalization hit home as the European integration process is keenly associated with the single market for goods and services and the free movement of people. Yet, people’s views about trade and 25 levels of migration do not automatically translate into people’s preferences for future European cooperation, especially among populist left party supporters. While much of the current discourse is directed by outward-looking people who embrace globalization and European integration and by those holding more parochial views that reject globalization and European integration, we have identified a third group: those who fear globalization but see the EU as a solution to the problem. This group supports populist left-wing parties and wishes to see more European cooperation, especially when it comes to financial assistance for struggling member states and acceptance of EU migrants, compared to the average European. These results suggest that while there is a small segment of the population that fears all forms of international cooperation and are more likely to support the populist right, the majority thinks that the EU could provide a vehicle to deal with problems associated with globalization. The findings might provide EU and national officials with ample impetus to shape the future of the EU post-Brexit.

Moreover, our results show that there is somewhat of a disconnect between people’s personal experiences with globalization and their perceived fears. While they report to have had more good than bad personal experiences, they do seem to fear what the process might bring in future. It seems fair to say that addressing these fears constitutes the key challenge for mainstream parties of left and right in decades to come. Only by doing so can voters be “won back” from their populist challengers.

Political leaders and parties all over Europe seem to be realizing the need to adapt. Rightly so. Our figures show once more that considerable numbers feel insecure about their ability to cope with the future. They feel threatened by how the world is evolving and what this evolution will mean for them and – more importantly – for their children. These fears are not necessarily economic in nature, according to our data, but touch upon security, migration and the protection of citizens’ rights. They also touch upon status issues and worries about losing one’s place in the world. The relation between place and space, between stability and change, seems to be out of kilter for significant numbers of people.

Restoring self-confidence might be a promising answer to the general feeling that made “take back control” a success. “Give back confidence” rather than “take back control”. It goes without saying that political action cannot hope to control the entire future. However, a smart policy mix can certainly increase people’s confidence in their ability to deal with uncertainty and foster societal resilience. This is a task for political leaders with a love of the long haul.

Left-wing politicans and thinkers may be well-advised to note that economic and inequality issues rank at the bottom of people’s priorities at the moment. Even those who fear globalization define it in economic terms but still put security and migration on the top of their to-do list.

Right-wing politicans and thinkers on the other hand would be ill-advised to assume that the wish to “feel safe” translates into the will to “seclude oneself”. 64 percent of these who embrace globalization as well as 45 per cent of those who fear it support integrated policy solutions at EU level. So far, we have not been able to produce any evidence for the notion that “people generally see the nation state as a safe haven”.

Successful measures cannot exclusively be based on securing economic growth or reducing immigration and this means that right-wing as well as leftwing politicians should be wary of their analytical reflexes. And they cannot be exclusively short term-ist. So they have to be wary of their political reflexes as well. Making people feel safe in an increasingly interconnected world will require new thinking on both sides of the political spectrum.

Alexander van der Bellen and Emmanuel Macron have brought proof that political campaigns can be won with a straightforward, openly pro-European liberal and inclusive worldview. In our European societies, there clearly is a desire for leadership and a sense of direction that can be put into simple words. Yet, ideas alone will not be enough, actions must indeed follow. In its early days, the European Union and its political leaders did a great job in connecting people, member states, markets. Today, they will need to find ways to make people feel safer and securer in these connections. This will be the key challenge for policy makers at the EU and national level for years to come.

References

de Vries, Catherine E. (2018) Euroscepticism and the Future of European Integration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Guiso, Luigi, Helios Herrera, Massimo Morelli and Tomasso Sonno (2017). Demand and Supply of Populism (No. 1703). Einaudi Institute for Economics and Finance (EIEF). Funke, Manuel,

Moritz Schularick, and Christoph Trebesch. 2016. ‘Going to extremes: Politics after financial crises, 1870–2014.’ European Economic Review 88: 227-260.

Mudde, Cas and Cristobal Rivora Kaltwasser (2013) Populism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Inglehart, Ronald, and Norris, Pippa (2016) ‘Trump, Brexit, and the Rise of Populism: Economic Have-Nots and Cultural Backlash.’ HKS Working Paper No. RWP16-026, Harvard University.

Method

This report presents an overview of a study conducted by Dalia Research in July 2017 on public opinion across 28 EU Member States. The sample of n=10.755 was drawn across all 28 EU Member States, taking into account current population distributions with regard to age (14-65 years), gender and region/country. In order to obtain census representative results, the data were weighted based upon the most recent Eurostat statistics. The target weighting variables were age, gender, level of education (as defined by ISCED (2011) levels 0-2, 3-4, and 5-8), and degree of urbanization (rural and urban). An iterative algorithm was used to identify the optimal combination of weighting variables based on sample composition within each country. An estimation of the overall design effect based on the distribution of weights was calculated at 1.46 at the global level. Calculated for a sample of this size and considering the design-effect, the margin of error would be +/-1.1 % at a confidence level of 95 %.