Executive Summary

The Eurozone crisis has proven to be a stress test for the European Union. While recovery may be on its way, the recession has left a mark on public opinion. Feelings of discontent and anger over Brussels’ response to economic downturn and the influx of refugees seem to have caused public support for the European project to plummet to an all-time low.

This, at least, is the popular perception portrayed in media reports and commentary. But is it really the case that euroscepticism has become the norm in 2015?

This report suggests that caution is in order. Our research demonstrates that public support for the EU is ambivalent, and that knowledge about the EU is quite high, in fact higher than was documented prior to the crisis. Yet to know the European institutions and its politicians does not mean to love them. While the majority of citizens support their country’s membership of the Union and, within the eurozone, membership of the euro, they are not satisfied with policy direction in the EU. What is more, while a large majority favours further political and economic integration, the same respondents say that they espouse negative views about the EU when talking to friends. This seems to suggest that they are conflicted. Put simply, people support the idea of a united Europe, but are increasingly weary about its current direction.

Interestingly, we do not find that the nation state is seen as the alternative; quite the contrary. Europe’s citizens may be dissatisfied about the current state of affairs in Brussels, but they are equally unhappy with the situation in their national capitals. The only clear exception to this pattern is Great Britain. The study relies on survey data and an embedded experiment carried out in July 2015 that covers public opinion in the EU28 as well as an in-depth look into opinion in the six largest member states.

What Stands Out About EU Citizens’ European Preferences?

- Support for membership is high throughout the Union (71 %). It is lowest in Great Britain (59 %) where, nevertheless, the majority of voters — in July 2015 — would have supported for EU membership in a referendum.

- The majority of people in the Eurozone support the Euro (63 %), and support for the Euro is equally high in southern member states, even though these populations were hardest hit by the Eurozone crisis. That said, citizens in non-Eurozone countries strongly oppose the Euro (85 %), and support for the Euro is lowest in Great Britain (14 %).

- On average, people in the EU favour more political and economic integration in the future (59 %). But this support is slightly higher in countries that are part of the Eurozone (64 %). It is especially high in the southern member states (71 %). The fact that southern member states are generally more supportive of integration is interesting, as they have experienced the adverse effects of the Eurozone crisis most severely, and have had to suffer controversial austerity policies as a result.

- Contrary to findings in the past, citizens in Europe today, and especially those in the Eurozone, are much more knowledgeable about the EU. 68 % of EU citizens and 74 % of citizens in the Eurozone display high knowledge European affairs. Europeans are also more familiar with the leading figures in the EU. Even though national leaders receive the highest recognition rates (Merkel 82 %, Cameron 74 %, Hollande 62 %), their European counterparts score surprisingly highly. More Europeans have heard of Jean-Claude Juncker and Martin Schulz (both 40 %), Donald Tusk (34 %) and Mario Draghi (34 %) than of Matteo Renzi (32 %) or Mariano Rajoy (23 %). Again, Britain is the exception with more people having low (52 %) rather than high knowledge (48 %), and with significantly fewer people familiar with key European actors.

- While support for the European project (measured by support for membership and within the Eurozone support of the Euro) is high, policy support is low. People are on average dissatisfied with the direction in which the EU is moving (72 %), more so in the South (81 %), and especially in Italy (89 %). That said, people are equally dissatisfied about policy direction in their own country, less so in Great Britain, Poland and Germany.

- People see the opening of borders and economic growth as the EU’s biggest achievements, while they view peace and security and the fostering of economic growth as Europe’s biggest policy needs.

- When asked whether they would speak positively or negatively about the EU to friends, people on average said they were equally likely to do either (53 % positive, 47 % negative). But people in non-Eurozone countries are more optimistic. This difference is driven primarily by the strong optimism of the citizens in the East. The Danish, British and Swedish are more negative.

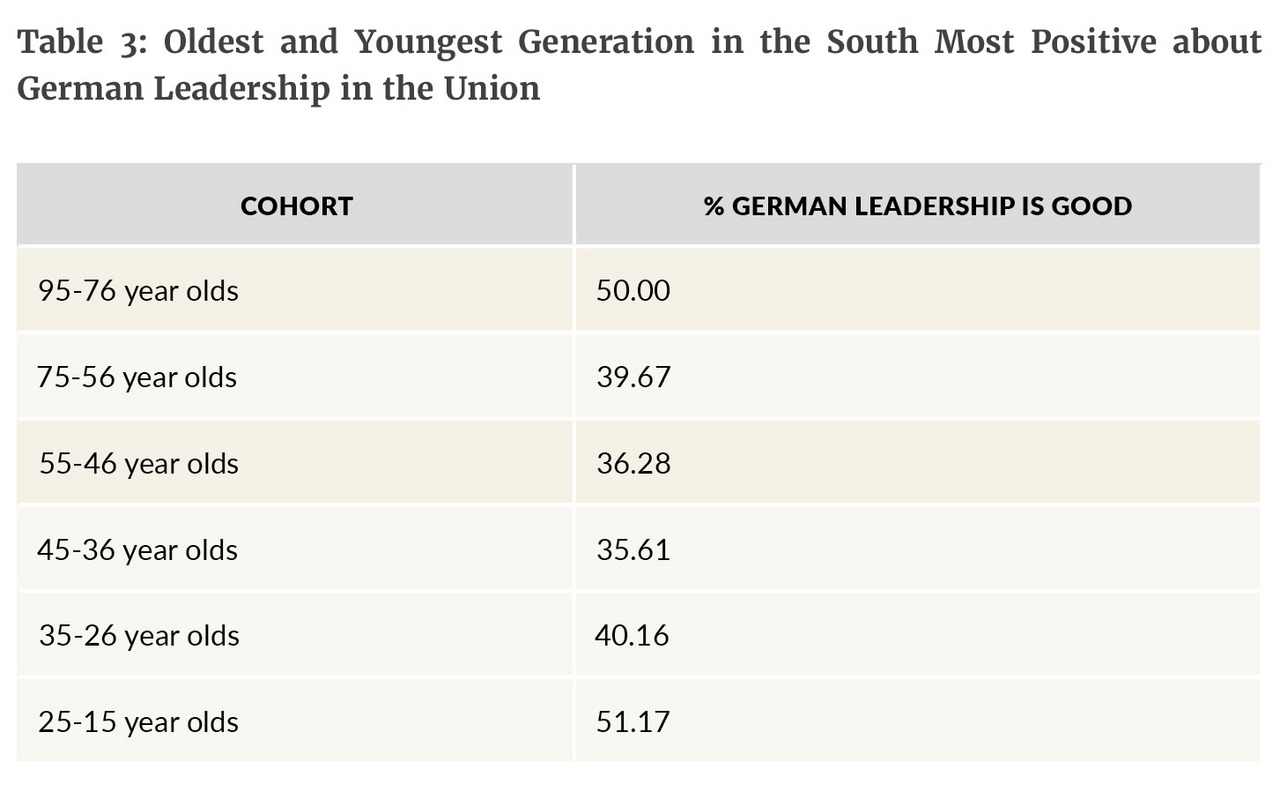

- Europeans are on average positive about German leadership in the Union (55 %), although Germany’s role in the South is evaluated quite negatively (60 %). Interestingly, the results suggest that the youngest generation of 15 to 25-year-olds in the South hold the most positive views about German leadership (51 %).

What Stands Out About Preferences for EU Reform?

- On average, EU citizens prefer an EU that is not too costly (they don’t mind paying up to € 35 per capita a year). They like the EU’s current size. It should be designed predominantly to safeguard peace and security as well as promote economic growth. And they would like to have a say in the Union more often through referenda.

- EU citizens as a whole strongly oppose the idea of a directly elected EU President taking decisions, even citizens who clearly favour more political and economic integration. People are on average largely indifferent about national governments or the European Parliament being the key decision-makers. They are only slightly less enthusiastic about the European Commission taking decisions compared to the European Parliament.

- Important cross-national differences in EU reform preferences exist. For example, the Spaniards and Poles, currently net recipients of the EU budget, are willing to pay more for the EU in the future while Britons, French, Germans and Italians — all net contributors — are not. Interestingly, the French are equally enthusiastic about the prospect of decisions being taken by a directly elected President rather than the European Parliament, while the British clearly prefer national governments being in control, or decisions being made through referenda. Finally, we find differences based on policy preferences: EU citizens in the South and East care significantly about economic growth, while citizens in the North favour a Union dealing primarily with peace and security. The latter view the regulation of immigration as of equal importance to that of growth.

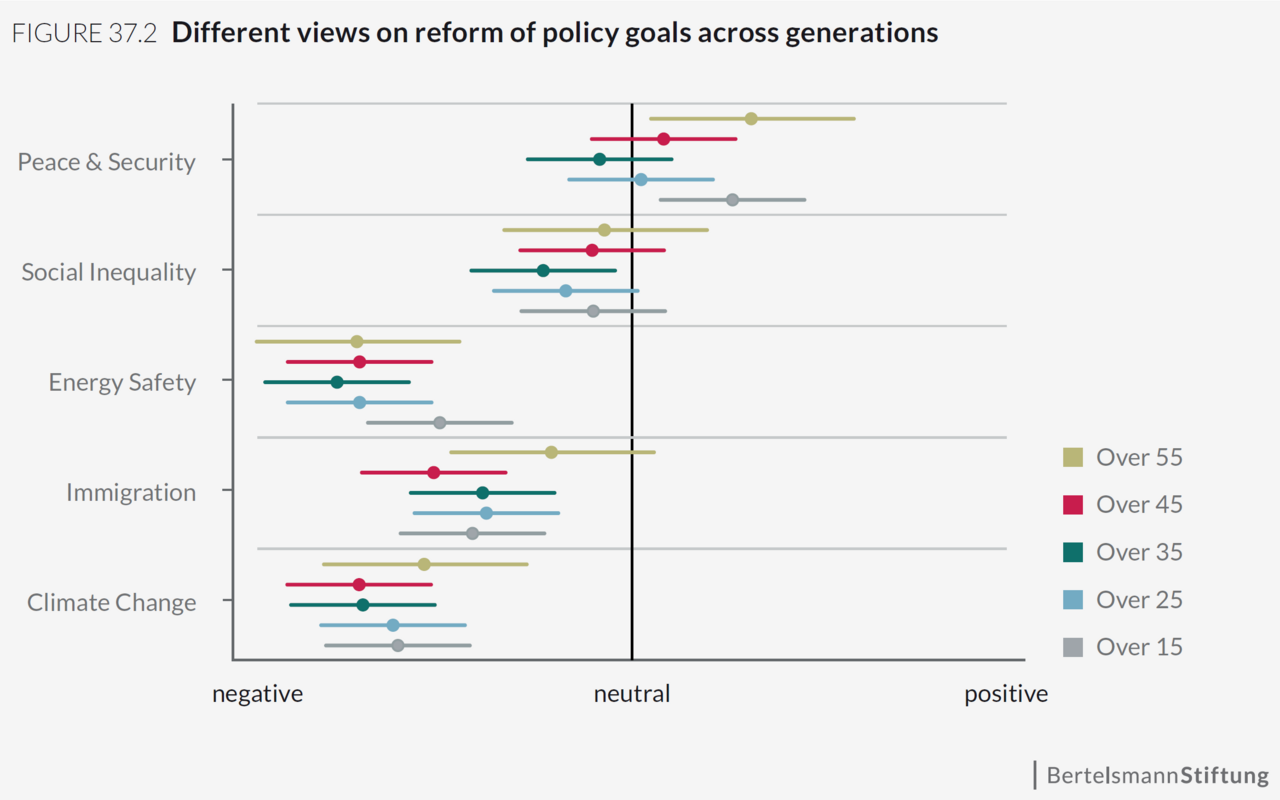

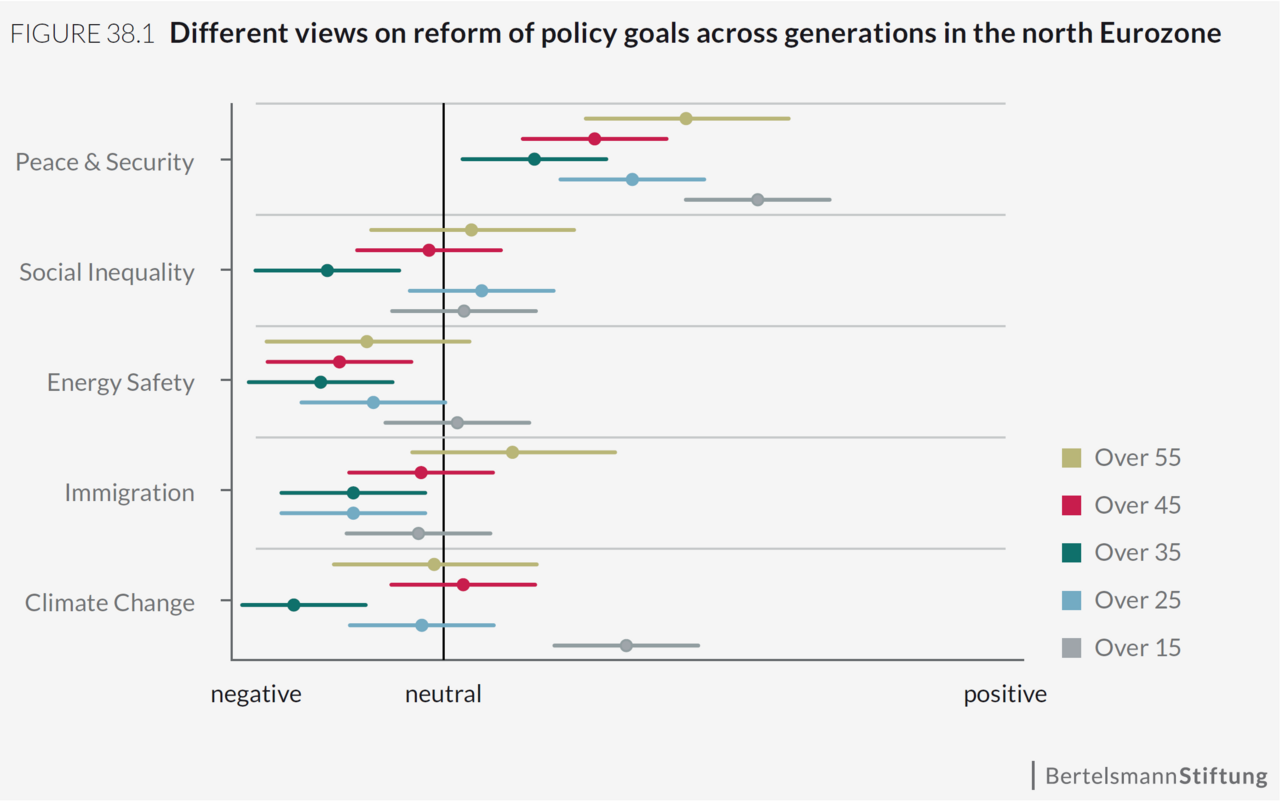

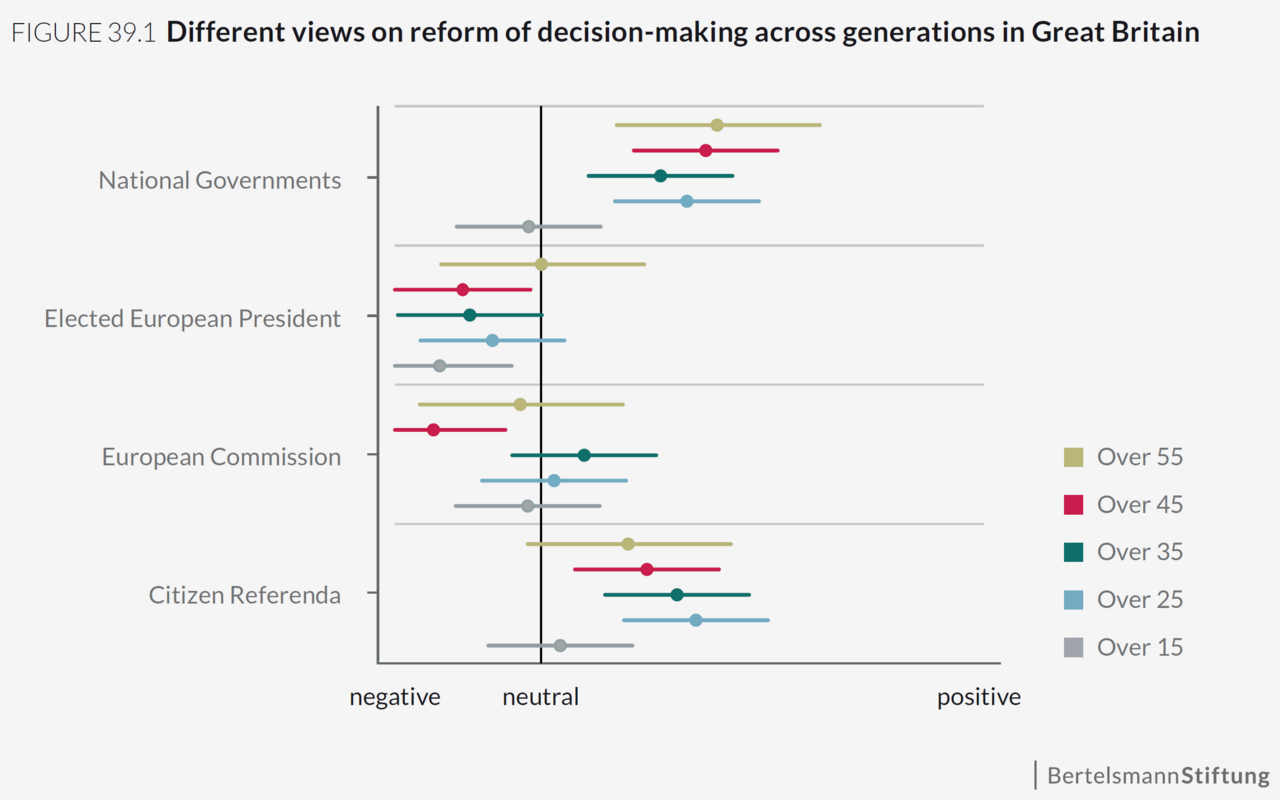

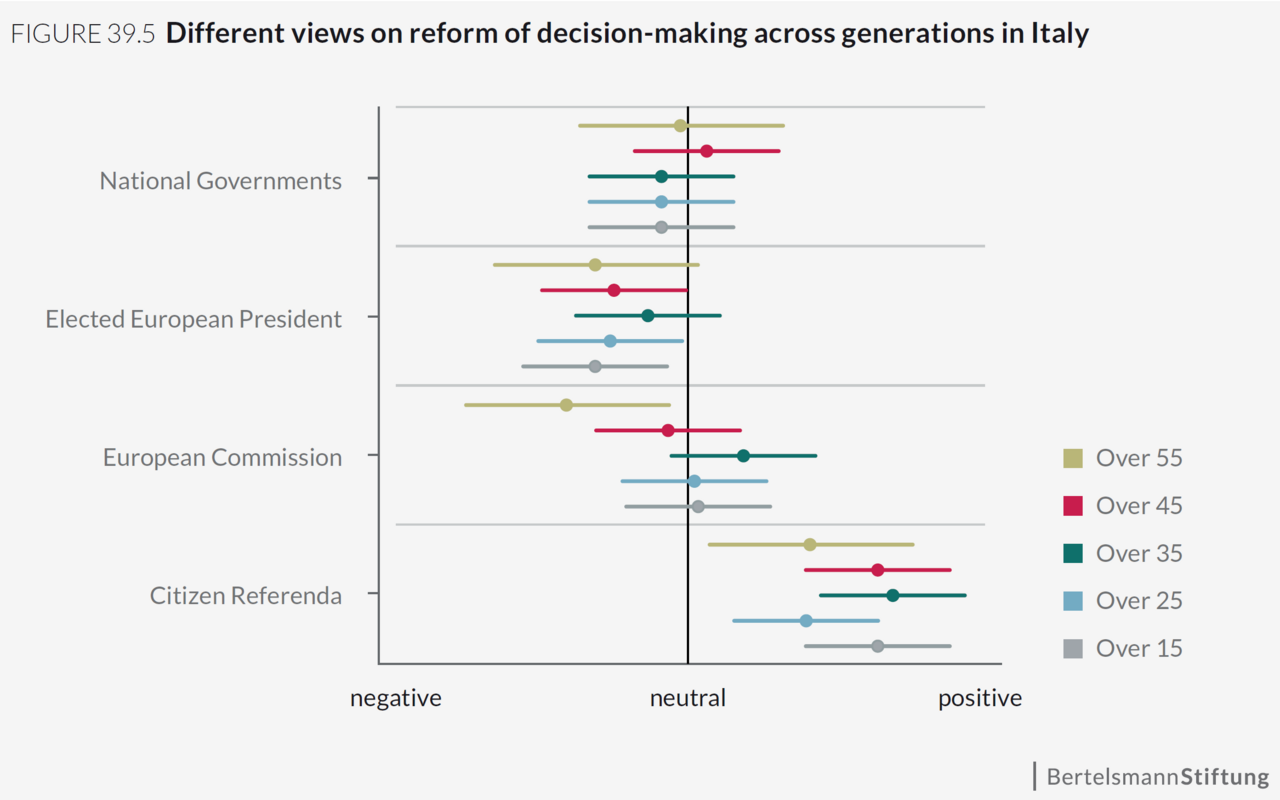

- Although we find no differences based on gender, EU reform preferences do differ based on age. Generations primarily disagree about who should take decisions in the EU and which policy goals the EU should focus on. In France, Italy, and Spain, for example, younger generations favour decision-making through referenda rather than the European Parliament, while in Germany older generations do. When it comes to policy preferences, we find that both the oldest and youngest generations in the EU favour an EU that safeguards peace and security over one that promotes growth.

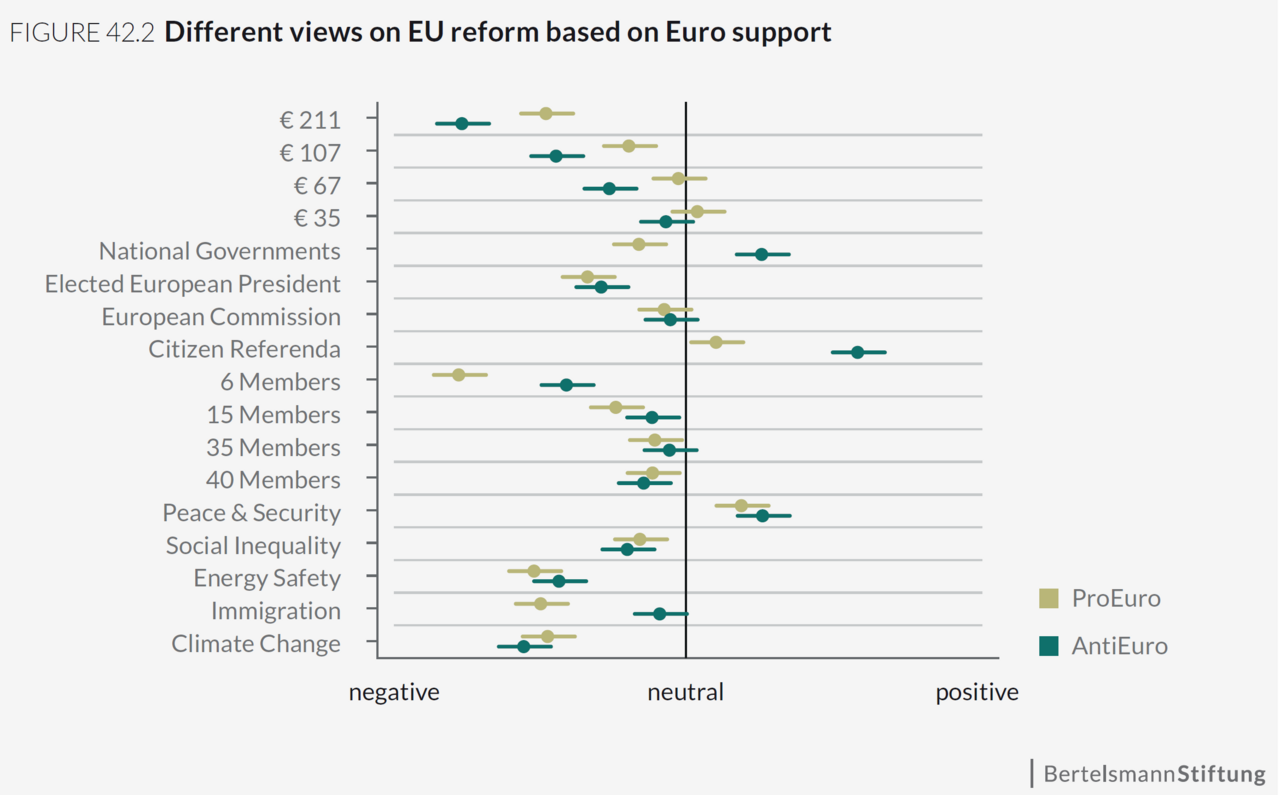

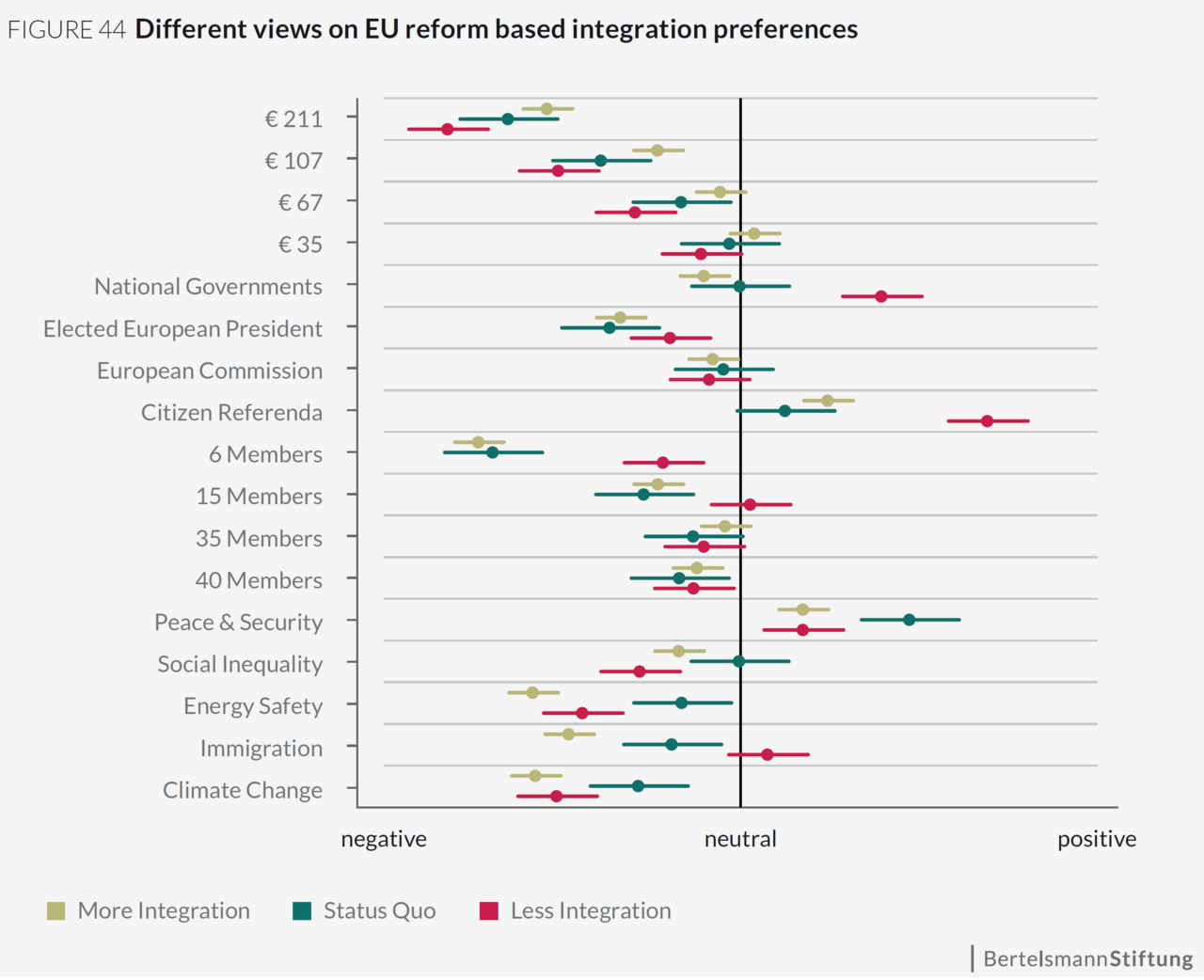

- When it comes to how EU preferences relate to support for EU reform, we find no differences based on the level of EU knowledge. We do, however, find clear differences based on overall level of scepticism about the EU. Regardless of whether people are sceptical about their country’s membership in the Union, the Euro, further political and economic integration or overall policy direction, sceptics differ primarily in their views about who should to take decisions in the Union. In contrast to supporters, sceptics are much more opposed to a Union in which European actors make policy. The type of EU that reform sceptics most want to see is a move towards more national control, either by means of citizen referenda in which national publics decide or through national governments.

- Alongside more intergovernmental decision-making, sceptics also value an EU that regulates immigration more, with some ascribing this greater priority than the promotion of economic growth.

- There are, of course, people who are highly supportive of the European Union and its politics. They are much less opposed to European institutions taking decisions for example.

What does this mean for the future of the Union and attempts to reform it?

We maintain that three things are important in this respect. People do support the idea of a united Europe, but are increasingly weary about its current execution. They are largely dissatisfied with many of its current policies, and are keeping a close eye on what is being done. Also, they are much more informed about Europe. Finally, people seem to care deeply about who governs them.

The Eurozone crisis has left a mark on public opinion. We find that contrary to past findings, citizens in Europe today, and especially those in the Eurozone, are much more knowledgeable about the EU. This improved knowledge does not necessarily lead to more approval. This is an important finding for those who seek to increase support for European integration merely via better communication. Our data reveal a (much) more nuanced picture.

While support for the Union is high, policy support is not. Hence, a more attentive citizenry makes it even more important for the EU to perform not only in terms of outcomes, but also in terms of procedures. More than ever, political leaders need to defend what they think is the best way forward for European politics. With the political culture of the EU being far from transparent, political leaders must find a way to argue openly about policy measures without being perceived as divided, nationalistic and incapable of taking decisions.

In any representative system, the procedural aspect is particularly important as individuals rarely get everything they want in terms of outcomes. What counts then is the belief that institutions provide a fair articulation of individual interests. One reform that most EU citizens agree on in this context is the implementation of referenda. At the same time, they oppose the handover of power to a directly elected President. They clearly prefer a diffusion of power over the concentration in Brussels. Implementing an element of direct democracy in the institutional setting of the EU might be a fruitful way to reassure citizens that they have some control over “what happens in Brussels”.

Overall, these results convey a message of hope for European officials and political actors in the member states. Europeans have not deserted the European project. They generally support the EU, the Euro, and even further political and economic integration. As they pay close attention to what is happening at the European level, people today know more than ever before about European politics.

High levels of political knowledge and awareness have consequences. People now pay attention to European politics but they are not satisfied with what they see. European political decision-making has clearly given its people an inside look into how difficult it is to craft policies to address the looming societal challenges in all 28 member states. Thus, while system support is high, policy support is not. If elites fail to address discontent over policy outcomes, worries about how decisions are made and goodwill may fade. If people feel that their voices are not heard in Brussels, they may turn against the project altogether. Setting aside these concerns may seem tactically beneficial to national governments in the short term, but the long-term consequences may threaten the very existence of the Union.

The Union Needs Reform, But Will the European Public Support It?

In Focus

The Eurozone and refugee crises have pushed reform of the EU to the forefront of the political agenda. How can an union of 28 states with a population of over half a billion be reformed to best address future crises and challenges? Finding an answer is extremely difficult, not only because actual reform proposals range from fully fledged political union to a partial repatriation of powers to nation states, but also because we lack data about support among the national populations for reform. Ever since the ‘no votes’ in the 2005 referenda on the Constitutional Treaty, leaders in Brussels and national capitals have been facing a new political realty. The EU is a highly divisive topic among national populations (de Vries, 2007; Kriesi, et al., 2008; Hobolt 2009). Experts are divided, too. Some, such as former Commission economist Paul De Grauwe and Nobel laureate Paul Krugman call for the creation of a political union that would aid the Euro in withstanding economic shocks, and secure financial stability in the long run. Others, like Council President Donald Tusk, warn that further pooling ofsovereignty at the EU level might provoke a serious backlash by national publics and eurosceptic political entrepreneurs.

Indeed, the question of what kind of EU reform is needed and feasible is high on the political agenda. On October 7th this year, the German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, and the French President, Francois Hollande, gave a joint speech at the European Parliament in Strasburg. They underlined that in their opinion the only way for Europe to take on the many challenges it is facing was to stand united be it the Euro crisis, the refugee crisis, the wars in Ukraine and Syria or the fight against the global warming. Therefore, they argued, further integration will be needed to improve the functionality of EU bodies that have been particularly tested and displayed their weaknesses over recent years. Namely the economic and monetary union, the Schengen area, and the external policy of the European Union. Meanwhile the European Commission put forward its vision for closer economic and monetary Union with the 5-President report in June 2015. It also presented an action plan to address the refugee crisis in September of the same year. So further reform seems inevitable. However, it is only if political leaders in Brussels and across European capitals provide a vision that can be shared by a majority of Europe’s 500-million-strong population, can political and economic reform be sustainable. If EU and national leaders move swiftly to further pool policy and institutional competencies without the backing of the EU public, this will most likely backfire.

Both pundits and scholars argue that political elites in the past have been so eager to pursue integration that they have lost track of the concerns and desires of citizens. Elites have also failed to persuade citizens of the wisdom of their policies. Instead, many argue, elites have moved ahead with European integration despite insufficient public support. This became painfully evident in recent electoral contests in Brussels and throughout Europe’s national capitals when accusations that political elites were out touch, though perhaps politically motivated, demonstrated the importance of understanding public preferences for reform. What kind of reform do national publics support?

While studies about support for European integration are abundant (see Hobolt 2012, Hobolt and de Vries 2015 for overviews), we know virtually nothing about EU citizens’ opinion on possible reforms. This is worrisome given that a decade ago, attempts to reform the Union through the Constitutional Convention and the Constitutional Treaty failed dramatically to garner support among national publics. Against this backdrop, it is imperative to provide a comprehensive understanding of public support for possible reform of the

Union. This report presents the findings of a detailed empirical analysis that does exactly that. Building on and extending current work on public support for

European integration, we examined the trade-offs between different aspects of integration. Specifically, we focused on four dimensions of support for EU reform:

- The functional dimension:

What type of European integration do EU citizens want? - The communal dimension:

With whom do EU citizens want this integration? - The utilitarian dimension:

How much are EU citizens willing to pay for this integration? - The institutional dimension:

How do EU citizens want the European Union to be governed?

These questions capture the key dimensions of support that have been identified by experts, and represent some of the most important trade-offs that citizens face. However they have not until now been systematically examined in the context of possible reform of the Union, or in an experimental setting that would allow us to capture their causal impact. The functional dimension relates to the policy that the EU should be promoting. Studies that compare the preferences of elites and ordinary citizens for the policy content of integration are relatively rare, but those that exist show that while elites favour integration in policy areas like trade and finance, citizens would like EU policy-making to concentrate on social policy and employment (Hooghe 2003, Müller et al. 2012). The communal aspect of European integration refers to the political community of the Union. From existing work we know that the degree to which citizens identify with fellow EU citizens affects the way they evaluate the integration process (McLaren 2002, Hooghe and Marks 2005). The utilitarian dimension signifies the costs that citizens are willing to pay for closer cooperation in Europe and follows from the cost-benefit approach to EU support (Gabel 1998). Finally, the institutional dimension relates to the way decisions are taken in the EU. Following work that suggests that the democratic deficit affects people’s views of European integration (Rohrschneider 2002), decision-making procedures in the union should be related to support for EU reform. These four dimensions are at the core of our data collection.

Our Method: A Conjoint Experiment Embedded in a Survey

This study provides the first in-depth examination of public support for diverse EU reform proposals across member states. Specifically, we utilize a novel data collection approach, namely experimental conjoint analysis that originates from marketing and psychology research and was recently adapted to suit questions related to political science. (Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto 2014). It maps out reform proposals that vary in terms of their functional, communal, utilitarian and institutional characteristics — and that have the most support among European citizens. We explore how these characteristics affect public support for EU reform by varying the features of each reform proposal. In other words, the study provides respondents with different combinations of values of the functional, communal, utilitarian and institutional dimensions. Conjoint experiments, which were developed in psychology and marketing, consist of respondents ranking or rating two or more hypothetical choices, in this case reform proposals for the EU. These hypothetical choices have multiple attributes, that is to say they vary on different dimensions. These dimensions are defined by the researcher on the basis of the scholarly literature, and in our case refer to the functional, communal, utilitarian and institutional dimensions outlined above. The objective of the conjoint experimental design is to estimate the influence of each attribute, for example the number of member states in the Union (communal dimension) or the costs of integration per person per year (utilitarian dimension) on the choices and ratings of the respondents. In order to make sure that alternative explanations are addressed, the political scientist Jens Hainmueller and several colleagues (Hainmueller, et al. 2014) have proposed a conjoint method using fully randomized designs.

Why is a conjoint experimental design most appropriate for examining public support for EU reform? Traditional survey research — upon which our current knowledge of support for European integration is based, including our own work — makes it difficult to trace complex and multidimensional preferences. In addition, it suffers from well-known causal inference problems. Put differently, it is difficult to make any causal claims about the effects of different dimensions on choice using the data that is available, given that we do not know in which direction the causal arrow flows. Finally, do opinions reflect real behaviour? Validation studies have shown that conjoint experiments perform remarkably well in predicting real-world behaviour (Hainmueller, et al., 2015). Hence, a conjoint experiment helps us maximize the external validity of our findings. When it comes to multidimensional preferences, a fully randomized conjoint experiment, in which survey respondents compare different sets of two possible proposals for EU reform and choose between them, allows us to assess the influence of different features of the proposed reform on how respondents evaluate a given proposal relative to another. One of the advantages of using a fully randomized design — that is randomizing the exact values on the different dimensions that feature on a reform proposal — is that the causal effect of the features of reform proposals on public support are non-parametrically identified. This means that it is not necessary to rely on assumptions about the functional form that maps reform proposal features on support (see Hainmueller, et al., 2014).

The randomization also ensures that the treatment groups are comparable with observable and unobservable confounding factors, that is to say with respect to alternative explanations. For example, respondents might interpret some of the information provided differently, which could affect the extent to which their support for an EU reform proposal depended on its specific design features. However, because of the randomization applied to a large sample, any potentially confounding variables will be distributed uniformly across treatment groups. Therefore, these groups will remain comparable, which means the estimates of how different reform features affect public support for EU integration remain valid even in the presence of differences in respondents’ subjective interpretations and beliefs.

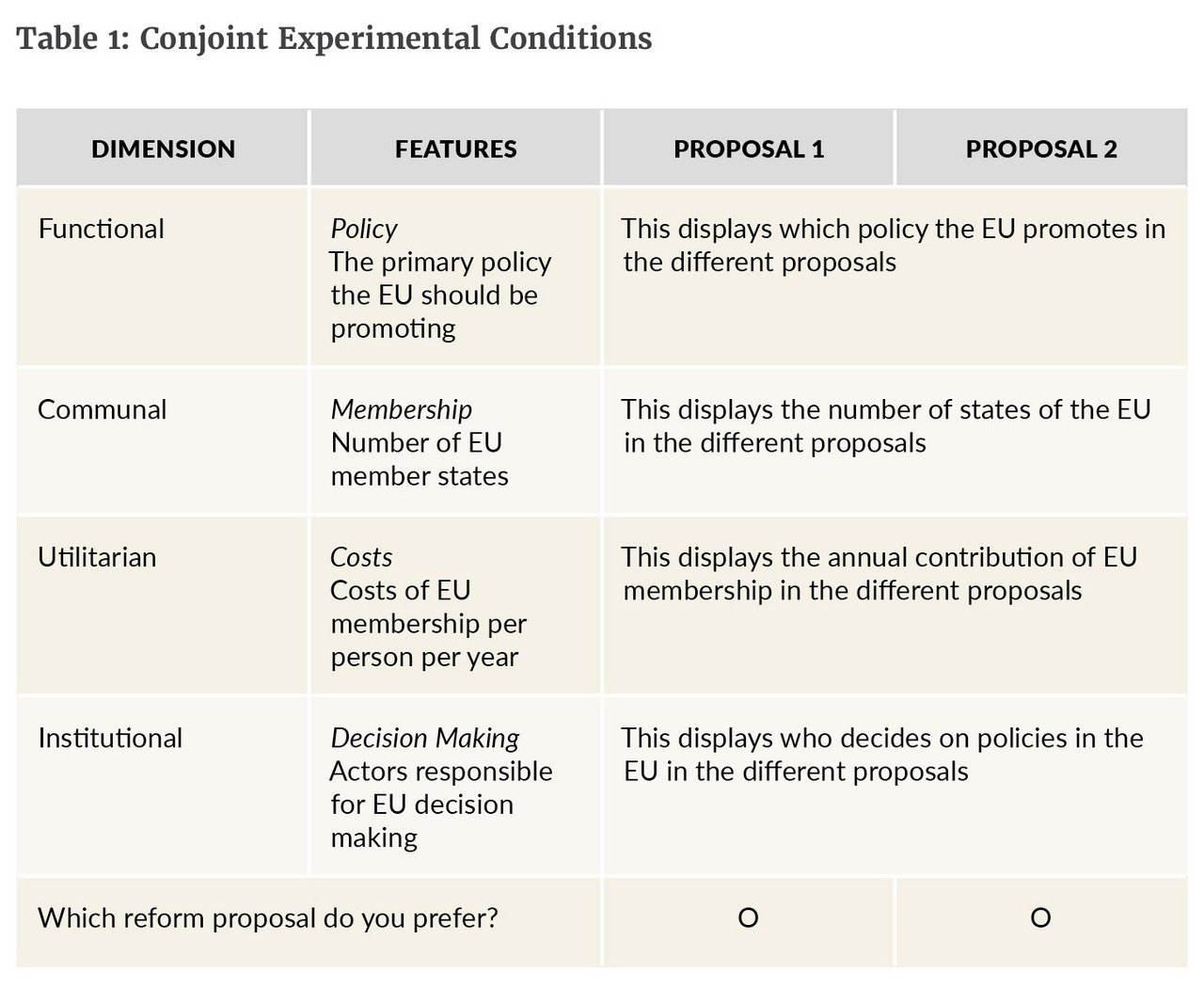

Table 1 provides an overview of the conjoint experimental design that was used. In the survey, respondents were shown two hypothetical EU reform proposals and asked to choose between them. Each respondent was randomly assigned four of these binary comparisons of EU reform proposals. Respondents were presented with a paragraph briefly explaining the task they were about to complete.

Subsequently, respondents were presented with four binary comparisons of different reform proposals. For each of the four binary comparisons respondents were shown a table (see Table 1) displaying two reform proposals. The order in which the features of the different dimensions was displayed to respondents was randomized, which circumvented the possibility that the order in which respondents received the information would affect the likelihood of them supporting particular reform proposals over others. After each table, respondents were asked which proposal they preferred. In addition, they were asked to rate each proposal by answering how likely it was that they would vote for either proposal in a referendum, ranging from not very likely to very likely. Overall, each binary comparison was comprised of two questions: a choice for one proposal and a rating of each proposal, and each respondent faced four binary comparisons.

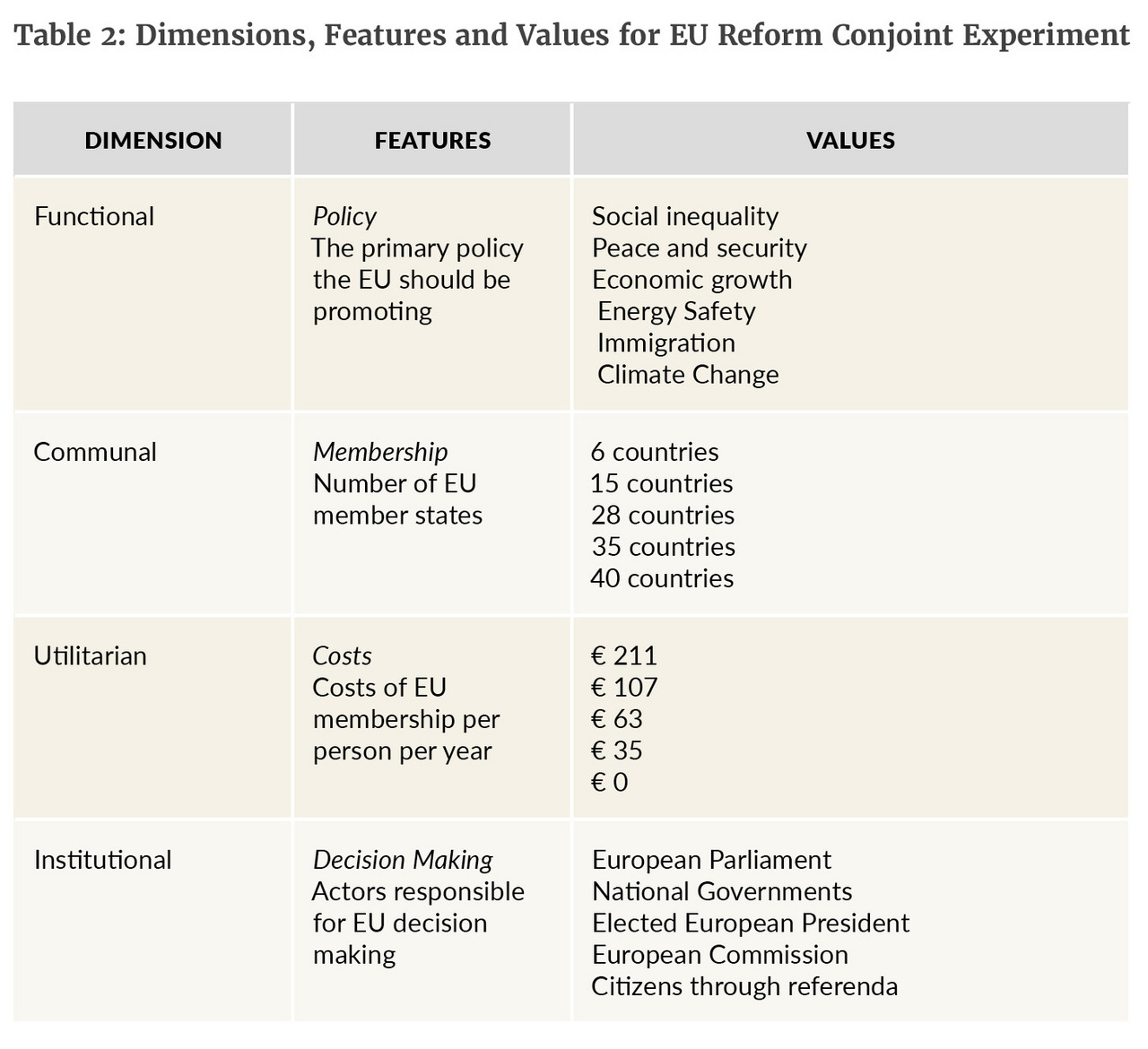

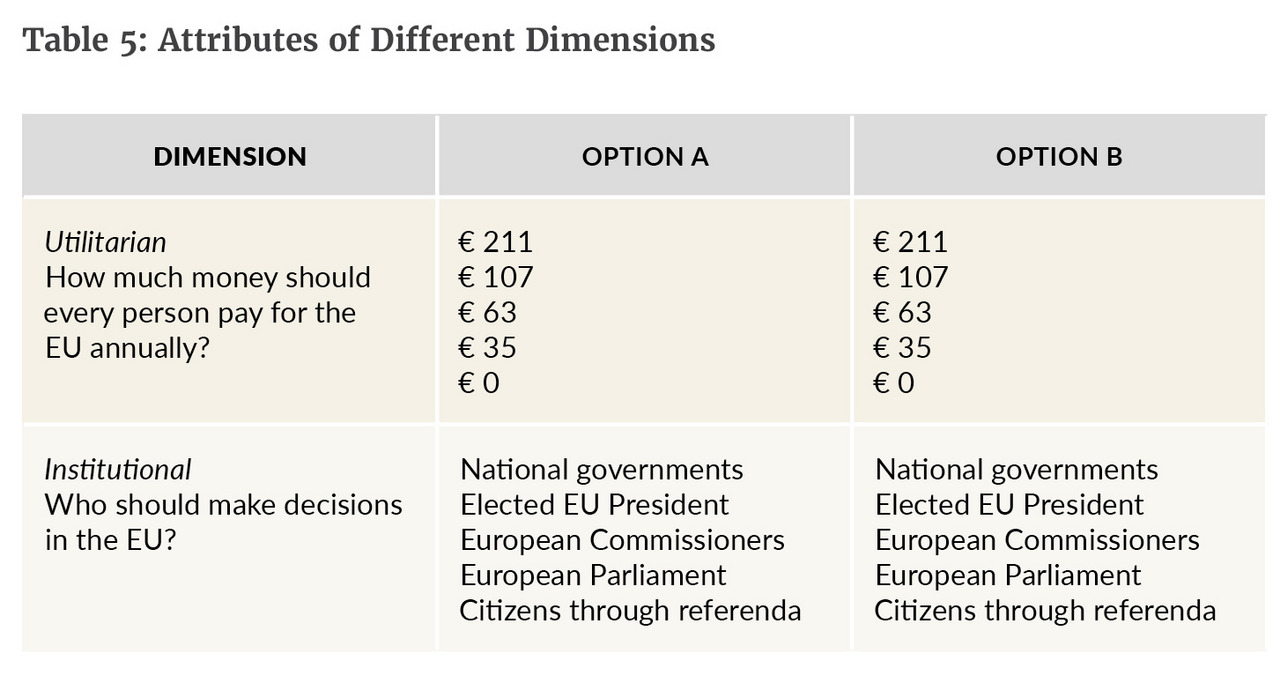

Table 2 shows the dimensions, features, and values used in the conjoint experiment. For each reform proposal presented to the respondent, the values for each dimension were assigned randomly. The choice of policy areas draws predominantly on work by Müller et al. (2012). In terms of the primary policies that the EU should promote, we added classical ‘European’ ones like peace and security as well as economic growth, but also inequality reduction and immigration, which have become salient in current debates on the context of the refugee crisis in the Mediterranean and the Eurozone crisis. In order to operationalize the communal aspect of European integration, the number of member states in the Union was included. This reflects debates about and studies of future enlargements and EU bailouts that suggest that regional divides are pertinent (Dixon and Fullerton 2014, Bechtel, et al. 2014). To explore the degree to which people are willing to sacrifice income for further integration, the annual net contribution per person per year was added (Anderson and Reichert 1995, Gabel 1998). The cost values are based on the 2009/2011 net contributions to the EU budget ranging from highest in Denmark (€ 211 per person per year) to lowest in Lithuania (€ 0 per person per year) which were publicly available. Finally, based on the discussion on the democratic deficit and governance in the EU (Scharpf 1999, Rohrschneider 2002, Føllesdal and Hix 2006), a feature that inquires into who decides on policy in the EU is added. This relates to the type of policy-making in the EU and ranges from technocratic governance (decision-making by the European Commission) to direct democracy (decision-making through popular referenda).

Alongside the conjoint survey experiment, we also fielded a questionnaire inquiring into attitudes and knowledge of the EU and their national systems. This allowed us to capture the general mood of respondents, put it in a national perspective, and determine how support for different reform proposals might also vary across different respondents. The public opinion data collection was carried out by Dalia Research GmbH using mobile phone applications. The fieldwork was conducted in July 2015 based on a representative sample of citizens from all 28 member states as well as representative samples from the six EU member states with the largest populations: France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain and the UK.

Our Findings: What Type of Union Do People Want?

Short Summary

The presentation of the results is divided into two parts. Part I presents an overview of the overall ‘European mood’ of European citizens in different regions and in the six largest member states in July 2015. It aims to place this in the context of people’s views about their national systems. The findings show that:

- Contrary to growing media reports and common opinion, Europe’s citizens can by no means be classified as euroceptics, but rather have ambivalent attitudes towards Europe (see also de Vries and Steenbergen 2013).

- While the majority of people, even in the bailout-battered South, support their country’s membership of the Union and in the Eurozone, they are not satisfied with the EU’s current policy direction.

- Moreover, we find that while a large majority favours further political and economic integration in Europe, Europeans would be equally likely to express negative views about the EU when talking to friends. This seems to suggest that while people support the idea of a united Europe, they are increasingly weary about its current governance.

- The only part of the Union that is perhaps best classified as eurosceptic is Great Britain.

- Finally, our results indicate that even if Europe’s citizens are dissatisfied with the current state of affairs in Brussels, they are equally unhappy with the situation in their national capitals.

Part II presents an overview of the findings based on our conjoint experiment. Against the backdrop of our main finding — that the majority of European citizens supports membership and further integration, yet is dissatisfied about the current state of affairs — it is pertinent to explore what kind of Union people would support in the future. We explored how costs, different decision-making institutions, the number of member states, and the policy goals pursued affect support for EU reform proposals.

We find that:

- Two changes to the current status quo are particularly popular among EU citizens: The use of referenda as a means of decision-making in the EU, and a Union that focuses on peace and security issues. In addition, people are indifferent about raising the average contribution to € 35 in the EU compared to the current level of € 0 per capita, but would not like to pay much more than that. They are strongly opposed to the notion of an elected European President taking decisions. Of all of the European actors, they prefer the European Parliament taking decisions. In terms of size, they favour the status quo of 28 member states. Finally, alongside to security and peace, people prefer an EU promoting economic growth rather than other policy goals such as securing energy safety, combatting climate change and regulating immigration.

- Key regional and individual level differences exist. They relate mainly to people’s views about who ought to make decisions in the Union and what the EU’s core policies should be. For example, in the case of how decisions are made in the EU, the French are largely indifferent about EU decision-making via a directly elected President or the European Parliament, most likely because they have a President at home. Yet the British and overall more eurosceptic citizens in other member states prefer a Union in which decision-making takes place via national governments or referenda, not through European institutions like the European Parliament or Commission.

- Finally, we find that EU reform preferences differ based on age. Generations disagree fundamentally on who should take decisions in the EU and which policy goals the EU should focus on. In France, Italy and Spain, for example, younger generations favour decision-making via referenda rather than the European Parliament, while in Germany it is older generations that do. When it comes to policy preferences, we find that both the oldest and youngest generations favour an EU that safeguards peace and security over one that promotes growth.

What Is the Mood in Europe on Europe?

Part I

Let us first explore whether European citizens have a modicum of knowledge about the EU that would then allow us to delve deeper into their attitudes towards different aspects of the EU, such as EU membership, the Euro and preferences for further political and economic integration. It is well established that voters differ with regard to their cognitive capacities and knowledge about politics (Converse 1964, Zaller 1992, Delli Carpini and Keeter 1996). In the literature on public support for European integration, a debate exists about citizens’ ability to form “real” opinions about the European integration process. It has been traditionally argued that European integration is one of the most complex political issues that European publics face, and that much of the day-to-day debate involves highly technical questions that citizens may find difficult to grasp (see for example Anderson 1998). The EU for much of its history was presented to citizens as a matter of foreign policy, about which citizens tended to have little knowledge (Holsti 1992, Karp, Banducci and Bowler 2003, de Vries et al. 2011). This was long supported by survey evidence. For example, results from the European Election Study in 1999 suggest that more than three quarters of European citizens did not feel sufficiently informed about the politics of the EU. Yet by 2014, the survey found that over 65 percent of European citizens were able to answer at least one of two “EU knowledge questions” concerning membership of Switzerland in the Union and a procedural aspect of European Parliament elections. Our survey results underscore this finding, and suggest that by 2015 people have in fact become quite knowledgeable about the EU and know some of the key EU officials like Commission President Juncker, for example.

Figure 1 displays the percentage of people who were able to correctly answer at least one of two factual knowledge questions about the EU. The first question asks whether Switzerland was a member of the EU, and the second question asks whether all member states have the same number of representatives in the European Parliament. A clear majority — 68 percent of people — answered at least one of these questions correctly. This is considerable and suggests that knowledge about EU affairs by 2015 is quite high. This slightly higher level of knowledge than reported in the European Election Surveys of the late 1990s or early 2000s is perhaps a by-product of the Eurozone crisis that has brought EU affairs to the forefront of political debate and media coverage.

To explore whether the Eurozone crisis did indeed increase the salience of EU affairs in the minds of ordinary people and made them pay closer attention and become informed, we explore differences between the Eurozone and non-Eurozone countries. If the Eurozone crisis at least partially contributed to information being more readily available, we ought to find that knowledge about the EU is higher in countries that are part of the Eurozone and thus more affected by the crisis compared to non-Eurozone countries. Figure 2 below suggests that this is the case: When evaluated by answering at least one of the two factual knowledge questions correctly, 74 percent of citizens in the Eurozone did so compared to just 56 percent in non-Eurozone countries.

The inspection of regional differences in figure 3 confirms this further. In the North non-Eurozone region, including Denmark, Great Britain and Sweden, we find an equal amount of people who have low compared to high levels of knowledge. In the East, where the Baltic states, Slovakia, and Slovenia have joined the Euro, but other countries like Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland for example have not, the gap between high and low EU knowledge is narrower than in the North Eurozone. This seems to indicate that knowledge about the EU is higher in regions that have the Euro and thus were most affected by the crisis, either as creditors or debtors.

Figure 4 to the right plots the proportion of people with high and low knowledge about the EU in the six largest member states. Again, knowledge is highest in countries that have adopted the Euro: France, Germany, Italy and Spain; and lower in the non-Eurozone countries: Great Britain and Poland. Interestingly, in one country, Great Britain, the proportion of people displaying low knowledge about the EU at 52 percent actually exceeds that of high knowledge (48 percent), although this gap is small. This low level of knowledge about the EU suggests that politicians and journalists have significant room for influencing public opinion in the upcoming Brexit referendum.

Our finding that knowledge about the EU is fairly high, yet not equally distributed across the Union, is further confirmed when we inspect name recognition of key EU officials and compare those to national heads of state. Providing this national yardstick is important and it puts our findings in a comparative context. Perhaps people are indeed quite informed about the EU in 2015, but still much less so compared to their national systems. We explore this possibility by focusing on two questions in our survey where we ask respondents whether they have heard of the following sets of names:

- Angela Merkel, François Hollande, David Cameron, Barack Obama, Ewa Kopacz, Mariano Rajoy, Matteo Renzi, Alexis Tsipras.

- Martin Schulz, Jean-Claude Juncker, Mario Draghi, Jeroen Dijsselbloem, Donald Tusk.

Figures 5.1 and 5.2 provide an overview of the name recognition of national heads of state and EU officials across all 28 member states. Not surprisingly, nearly all people recognize the names of the US President Barack Obama and German Chancellor Merkel, and a considerable amount of people have heard of the British Prime Minister David Cameron and the French President François Hollande. The national heads of state of Southern and East European countries, specifically Spain, Italy, Greece, and Poland, are far less known — with the exception of Greece’s Alexis Tsipras. Given that in the time frame of investigation, (July 2015), the Greek bailout talks were in full force, the name recognition of

Tsipras should not come as a surprise. It is perhaps surprising to see that a considerable share of people know the European Parliament President Martin Schulz, Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker, the ECB President Mario Draghi and the Council President Donald Tusk. In fact, more people know these top EU officials than the current Spanish or Italian Prime Minister or Polish Prime Minister. This seems to confirm our previous findings that in July 2015 knowledge about the EU and its officials is in fact quite high.

Do we again find that knowledge about the EU is higher in the Eurozone compared to the non-Eurozone? Figures 6.1 and 6.2 present the same information about name recognition of national and European leaders as presented above, but they seperate the results for countries within and outside the Eurozone. For name recognition of national leaders Obama and Merkel, we find little difference between the Eurozone and non-Eurozone member states. But for EU officials we find more variation. Except for Council President Tusk, people in the Eurozone are more likely to recoginise the names of top EU officials compared to those outside. Interestingly, this holds especially true for Draghi and Dijsselbloem. While in the Eurozone 44 and 20 percent of people recognize their names, these shares are much lower in the non-Eurozone, namely 13 and 6 percent respectively.

When we compare the name recognition of top EU officials across regions, striking differences emerge that suggest that the Eurozone crisis starkly increased knowledge about EU affairs. Name recognition is by far the lowest in the North non-Eurozone member states, followed by the East. Do note that most people in the East have heard of Council President Donald Tusk. Given that he was the Prime Minister of Poland, this might not be entirely surprising. Also interesting is the fact that name recoginition of Mario Draghi is enormous in the South: 69 percent have heard of the ECB President. In fact, as many southerners have heard of Draghi as have of French President Hollande. In the North non-Eurozone and East name recognition of Draghi is lowest.

Finally, figure 7 shows the proportion of people who have heard of top EU officials in Great Britain. British citizens not only hold the lowest level of factual knowledge about the EU, but they are also least aware of who its top officials are. Less than a third of British citizens have heard of the leaders of Europe’s legislative and executive institutions, Commission President Juncker, European Parliament President Schulz and Council President Tusk. Even fewer British citizens have heard of ECB President Draghi or the chair of the Eurogroup Dijsselbloem, at 9 and 4 percent respectively. Given that Great Britain is not part of the Eurozone, less knowledge about the latter two figures might not be surprising, yet the low levels of name recognition of other EU leaders underlines our previous result that knowledge about EU affairs is very low among British citizens.

Membership and Support for the Euro

After we have established that on average people are quite knowledgeable about the EU, we delve deeper into their EU preferences. When examining support for political systems, political scientists often make a distinction between two different modes of political support: diffuse and specific (Easton 1965). Whereas diffuse support refers to the evaluation of the regime, broadly defined as the system of government and the constitutional arrangements underlying it, specific support relates more to policy, that is the binding collective decisions and actions taken by political actors operating in the broader system of government (see Norris 1999). In the context of European integration, scholars have distinguished between regime support and policy support (Hobolt and de Vries 2015). Regime support signifies support for the constitutional settlement of the EU, as laid down in the various treaties, including support for membership of this Union. Policy support refers to support for the content of collective decisions and actions taken by EU actors.

Regime support is crucial to any system since it allows systems to retain legitimacy even when people become disillusioned with the performance of specific governments and policies (see Norris 1999). In established democracies, regime support is often taken for granted; yet in the context of the EU it is still fragile. Unlike most established nation states, the EU is characterized by a hybrid multi-level political system (Hooghe and Marks 2001). Moreover, there exists uncertainty about the scope of its competences, its demos, and its external boundaries. Moreover, the aims of the Union are contested by politicians and populations in many member states. This presents a considerable challenge to the European project (Mair 2007, De Wilde and Trenz 2012). At the same time, far-reaching economic and political integration in Europe means that the EU is increasingly dependent on public support as it lacks long-lasting loyalty to its goals and institutions like that found at the national level. Since the actions of all elites will occasionally fail to meet public expectations i.e., policy support in the EU will be variable, the Union needs a buffer against short-term policy failures through some degree of regime support (Scharpf 1999). Consequently, an examination of regime support in the EU is of vital importance.

Figure 8 provides an overview of the proportion of people that support their country’s membership of the Union. Specifically, we asked respondents the following question: “Imagine there is a referendum and you could decide whether your country stays as a member of the European Union. How would you vote? 1) I would vote for my country to leave the European Union, 2) I would vote for my country to stay in the European Union.” The findings in figure 8 suggest that on average broad-based support for EU membership exists throughout the 28 member states. Almost three-quarters of those surveyed (71 percent) would vote for their country to remain a member of the Union if a referendum about membership were held today.

Interestingly, support for membership does not vary much inside and outside the Eurozone. Figure 9 shows that while support for membership in the Eurozone is at 72 percent, outside the Eurozone 69 percent of people would vote for their country to stay in the Union. We do find that support for membership is at its lowest level in the North Eurozone region (Denmark, Great Britain, Sweden). Although 62 percent of people in these countries would vote to remain a member of the Union, 38 percent would vote against it, which is roughly 10 percent more than in the other regions (see figure 10).

If we inspect support for membership in the Union in the six largest member states, see figure 11, we find that overall support for membership consists of well over two thirds of the population in France, Germany, Poland and Spain, but is considerably lower in Great Britain and Italy. In these countries, the majority of the population would vote for their country to remain a member, but 41 and 38 percent respectively say that they would support an exit. The British findings are of course especially interesting given the prospect of a membership referendum in 2016 or 2017. Our findings confirm those of British polls conducted by YouGov and MORI that suggest that at the present time, a small majority of Britons would favour membership over exit.

Overall, these findings suggest that regime support as measured through membership preferences remains high even given the recent turbulence caused by the Eurozone crisis. But what about support for the Euro? Is it more fragile? It is important to remember that support for the Euro can be perceived as a form of regime support only in the Eurozone as these countries have opted for the common currency as a sign of the European project. For non-Eurozone members support for the Euro might rather constitute a form of policy support and therefore could be more fickle. Figures 12.1 and 12.2 show the distribution of answers to the following question: “Ok, now imagine there is referendum on the Euro as a currency. Do you want your country to have the Euro as a currency? 1) Yes, I would vote for the Euro as a currency, 2) No, I would vote against the Euro as a currency” for the EU28 and Eurozone versus non-Eurozone members respectively.

While figure 12.1 indicates that in the EU as a whole the share of people who would vote for the Euro in a referendum is about the same size as the one voting against the Euro, the findings presented in figure 12.2 show that this figure, masks great variation between Eurozone and non-Eurozone members. While in the Eurozone countries a majority would vote to keep the Euro as their currency, in the non-Eurozone countries a clear majority of 74 percent would vote against introducing the Euro. If we delve even further into possible regional differences in Euro support (see figure 13), we find that the opposition to the Euro is the greatest in Denmark, Great Britain and Sweden i.e., the North Non-Eurozone, followed by the East. Moreover, it is interesting to note that the support for the Euro in the South that was adversely affected by the Eurozone crisis is equal to support among the creditor countries in the North Eurozone.

Finally, figure 14 presents the average support for the Euro in the six largest member states in terms of population size. As expected, support for the Euro is lowest in Great Britain, only 14 percent of British citizens would vote for the Euro in a referendum. Quite unexpectedly perhaps, it is the highest in Spain, a country that was hit hard in the Eurozone crisis and has experienced austerity measures since then. However both support for membership and the Euro remain extremely high in Spain. Support for the Euro reaches the 60 percent mark in both France and Germany, yet compared to support for membership the Euro seems more contested in these countries. In Italy we find that there is only a slight majority that supports the Euro, namely 56 percent. This mirrors the slightly weaker support for membership compared to France, Germany, Poland and Spain found in figure 11.

On the whole, these findings suggest that regime support as measured through membership preferences and Euro preferences in the Eurozone is considerable. Italy shows the lowest support although a majority of Italians support their country’s membership in the Union and the Euro. In the non-Eurozone support for membership, with the slight exception of Great Britain, is high while support for the introduction of the Euro is low. Given the problems surrounding the Eurozone crisis and the Greek bailouts, this may not come as a surprise. Overall, regime support in the Union is substantial. This is important for the EU in order for it to weather past and current policy challenges, such as those concerning the Euro and the large influx of refugees from Africa and the Middle East.

Support for Further Political and Economic Integration in Europe

Average support for further political and economic integration in Europe is also high among Europe’s citizens. In our survey we solicited integration preferences using the following question:

“If you had to choose, which of the following statements best describes your overall attitude towards European integration?

- We need more political and economic integration across Europe

- Things should remain as they are today

- We need less political and economic integration across Europe.”

Figure 15 below shows the distribution of responses for our representative sample of all 28 EU member states.

The findings show that 59 percent of people prefer more political and economic integration in Europe, while only 24 percent prefer less and 16 percent wish the status quo to remain as it is. This suggests that not only do a majority of people prefer their country to remain in the EU, they also wish to see further integration. This picture might change when we consider regional and country differences as displayed in figures 16 through 18. Figure 16 shows that support for more political and economic integration is, with 64 percent, 14 percent higher in Eurozone countries compared to non-Eurozone countries.

The findings presented in figure 17 suggest that while support for further integration is far more pronounced in the Southern region, where 71 percent of people favour more political and economic integration, it is lowest in the North non-Eurozone region, where only 41 percent do. Support for further integration in the East and North Eurozone is almost identical with a slight majority, at 58 and 53 percent respectively, favouring more integration.

Finally, figure 18 indicates that only in Great Britain do we find an equal share of people favouring more versus less integration (both 39 percent). More than three quarters of Italians and Spaniards favour more integration. In Germany, France and Poland also a slight majority favour the same 56 percent. Put together, these findings indicate that on average people in the Union favour more political and economic integration in the future, but that this support is slightly higher in countries that are part of the Eurozone and especially in southern member states. The fact that southern member states are on average more supportive of integration is interesting as they have experienced adverse effects of the Eurozone crisis and had to implement controversial austerity packages as a result. As in the case of membership and the Euro, support for further integration is at its lowest level in Great Britain where only slightly more than a third of people favour more integration.

The Biggest Policy Achievements and Policy Needs in Europe

So far, we have reviewed people’s regime preferences and paid little attention to support for policies. Even though we found that people are quite knowledgeable about the EU, we cannot realistically expect them to have clear opinions about detailed policy proposals or outcomes. Rather we ask respondents about their views on the EU’s biggest policy achievements to date and the policy areas that need more attention. In order to facilitate responses, we provided them with a list of options:

Biggest policy achievements:

- Opening borders across Europe

- Establishing a common currency

- Creating a common agriculture policy

- Facilitating trade across Europe

- Securing peace and cooperation

- Supporting reform in Eastern Europe

- Fighting climate change

- Protecting consumers’ rights

- Creating jobs

- Protecting human and social rights

Policy Areas Needing More Attention:

- Harmonizing taxes across Europe

- Securing borders

- Reforming immigration policies

- Helping poor countries

- Strengthening consumer protection laws

- Fighting climate change

- Supporting economic growth

- Investing in infrastructure

- Reducing inequality

- Secure peace and security

Figures 19.1 and 19.2 present an overview of responses to both sets of questions. Within the EU28 people feel that both the opening of borders and the facilitation of intra-EU trade are Europe’s biggest achievements (46 and 45 percent each), followed by securing peace and cooperation (40 percent) and establishing the common currency, creating jobs and protecting human and social rights (37 percent). By far the most important policy priorities in the eyes of EU citizens are securing peace and security (61 percent) and supporting economic growth (54) in Europe.

Next to these policy priorities, people also view the reduction of social inequality (47 percent) and the reform of immigration policies (42 percent) of key importance. Figures 20.1 and 20.2 show the distribution of perceptions of the EU’s biggest achievements and most pressing policy priorities for Eurozone members and non-Eurozone members respectively. In terms of policy priorities we find few differences between people who reside in the Eurozone compared with those who reside outside. Differences regarding perceptions of the EU’s biggest achievements are also small, but we do find that while the opening of borders is perceived as Europe’s biggest achievement in the non-Eurozone, more intra-EU trade takes place within the Eurozone countries.

Finally, when we inspect regional differences in figures 21.1 and 21.2, we also find less disagreement between people’s views on the most pressing policy priorities compared to people’s perceptionof the EU’s biggest achievements. Across the North, South and East, people view peace and security as well as economic growth as the Union’s top priorities. When it comes to Europe’s biggest achievements in the North Eurozone, the opening of borders and the facilitation of intra-EU trade, and creating jobs were high on people’s lists, while in the North non-Eurozone human rights was considered a key achievement of the EU, much more so than opening borders. People in the South mentioned creating jobs, and peace and human rights, while in the East we find a pattern similar to the North Eurozone: people mention opening borders and trade first when thinking about the EU’s biggest achievements.

Overall, peace and security feature as the most important policy priorities in the EU, while the facilitation of trade and the opening of borders were mentioned frequently as Europe’s biggest achievements. Considerable regional variation exists.

Views on the Direction in which the EU and its Nation States are Heading

So far, we have established EU citizens’ regime and policy preferences without any reference to the national level. Now we delve deeper into popular evaluations of policy by comparing opinions about the policy direction in which they view the EU and their country moving. Recall that we suggested that research predicts that the likelihood of specific outcomes is sketchy at best (Zaller 1992, Delli Carpini and Keeter 1996). As a consequence then, political scientists often rely on general evaluations of the state of the country and /or the economy (see Kinder and Kiewit 1984, Anderson and Guillory 1997 for example). Following these insights, we tap into policy preferences by comparing and contrasting questions on people’s evaluations about the policy direction in which their country or the EU is moving. Figure 22 to the right provides a comparison between the proportions of people stating that the EU is moving in the right versus the wrong direction policy wise, and the proportions when people are asked to evaluate the policy direction in their home country. The results indicate that in the EU28, people see policies in the EU moving in the wrong direction (72 percent), but that they are equally sceptical about policies in their own countries (68 percent).

Interestingly, if we split these results for Eurozone versus non-Eurozone countries (Figure 23), we find that, within the Eurozone, people are on average more sceptical about the EU or their country’s policy direction compared to those outside the Eurozone. People within the Eurozone are 14 and 11 percent more sceptical about the policy direction of the EU and their country respectively compared to those outside.

In terms of regional differences as presented in Figure 24, we find that people in the South are most sceptical about the direction in which things are moving in the EU and in their respective countries, while people in the East are least sceptical about policy direction in the EU, and less so than about the policy direction in their own country. With the exeption of the East, people are slightly more sceptical about policy direction of the EU compared to their own country, although in the South these differences are almost negligible.

If we delve a bit further into the variation between countries by focusing on differences within the six largest member states (Figure 25), we find that Italians are most sceptical about both policy direction in the EU and their country, while Poles are least sceptical. In most countries, except for Germany and Great Britain, people are equally sceptical about policy direction in the EU compared to their own country. Only in Germany and Great Britain do we find that the difference between both evaluations is statically significant (p <.05). Germans are on average 9 percent and the British 12 percent more sceptical about policy direction in which the EU is moving compared to their own country, although the majority of them are on average more sceptical than optimistic about policy direction in their country.

These findings suggest that while we previously found that regime support is quite high in the EU, policy support is not. The majority of people in the 28 member states are weary of the EU’s policy direction. At the same time, they are also sceptical about the policy direction of their own country. People in the South, and especially Italians, are deeply sceptical about the direction things are moving in their country and the EU, while Germans and British display more scepticism towards the EU than the policies in their own country, albeit that still a majority of them feel that things are moving in the wrong direction in their own country.

How to Talk to Friends about the Union

Scepticism about the way things are progressing in the EU is also reflected in responses to the question: “Imagine you talk with a friend or colleague about the European Union. Would your conversation be 1) very positive, 2) positive, 3) negative, or 4) very negative.” Figures 28 to 31 display the number of people either responding positively (1 or 2) or negatively (3 or 4) in the EU28, the Eurozone versus non-Eurozone, across regions, and in the six largest member states respectively.

These figures indicate that on average people in the EU28 would be equally likely to talk positively about the EU to friends as they would be to talk negatively (figure 26). We find very little difference between Eurozone versus non-Eurozone countries, although people outside the Eurozone would be slightly more positive (56 versus 51 %). (Figure 27).

When we inspect the differences between regions, it becomes clear that the slightly more positive tone when talking to friends in non-Eurozone countries is primarily driven by responses from the East (figure 28). People within the North non-Eurozone would on average be more negative about the EU than positive (53 versus 47 %). We find a similar pattern in the South where people would more likely talk negatively than positively about the EU to friends, although the difference here is quite small. Finally, if we inspect differences across the six largest member states we find that the British, French and Italians are the least positive about the EU to friends, while the Poles are the most positive (figure 29).

All in all, these findings suggest that in our survey subjects are on average equally likely to talk positively or negatively about the EU to friends. In the East, especially in Poland, they would be the most positive by far, while British, French and Italians would speak least positively about the EU to friends.

German Leadership in the Union

A final attitude that we will consider before turning to our conjoint experiment is a respondent’s view about Germany’s role in the Union. Specifically, we asked respondents to consider the following: “Germany is often seen as taking a leadership role in the European Union. Do you think this is 1) very good, 2) good, 3) bad”. The figures to the right present the share of people either responding that they approve of Germany’s leadership in the Union (1 and 2) or they do not (3). Figure 30 provides this information for the EU as a whole. We find that the majority of people approve of Germany’s leadership in the Union, albeit the difference with disapproval, 55 versus 45 percent respectively, is rather small.

Interestingly, figure 31 demonstrates that approval of German leadership is, at 59 versus 53 percent, higher in the non-Eurozone compared to the Eurozone countries.

Comparing approval across the different regions (figure 32) suggests that it is the lowest in the southern member states and highest in the North Eurozone. Considering that Germany is the biggest creditor country and thus largely defends the creditor positions of the North Eurozone in the Euro Group against the positions of debtor countries in the South, these differences should not come as a surprise. Interestingly, when we look further into this by exploring differences across generations in the South (see Table 3), we find that approval in the South is actually highest amongst the youngest age cohort between 15 and 25, which is unexpected.

Finally, figure 33 explores differences in approval of German leadership in the six largest member states, and we find that Italians and Spaniards are most sceptical at 71 and 61 percent respectively, followed by the British at 52 percent. Approval of German leadership, however, is high in France and Poland as well as in Germany of course. These findings suggest that German leadership is quite contested in the South, which might be the result of the Eurozone crisis and austerity requirements proposed in Brussels largely under German leadership. The finding that approval among the youngest age cohort between 15 and 25 iss, at roughly 60 percent, the highest among all cohorts in the South suggests that these attitudes might change in the future.

What Kind of Europe Do Europeans Want?

Part II

Part I of the analysis demonstrates that citizens are largely conflicted about Europe. While on the one hand they support membership and further integration, on the other they are dissatisfied with overall policy direction in the Union, and not particularly enthusiastic about it when they talk to friends. While past research often implicitly assumed support for European integration to reflect fixed attitudes — either you are pro- or anti-EU — our findings echo recent contributions that suggest that it might also be useful to think of EU attitudes as inherently variable, namely reflecting differential degrees of ambivalence (de Vries 2013, de Vries and Steenbergen 2013). For example, EU citizens may like the idea of European integration in the abstract as secure peaceful state cooperation, but at the same time they may not have much appreciation for the actual policies that the EU pursues. Or they may like the majority of policies coming from Brussels, but object to the political process that yields them. Although many journalists, politicians and pundits often argue that the public is increasingly sceptical of further steps towards integration, based on the findings presented here we ought to qualify this claim. Public opinion towards Europe is best described as ambivalent, and thus we know from previous research malleable (Zaller 1992). We seem to be witnessing a process of growing uncertainty about the future of the integration process, especially when it comes to which policies are pursued.

Given that public opinion towards European integration is multifaceted we need to carefully craft survey instruments that allow us to understand which kinds of European integration and which types of reform Europeans actually want. The multi-dimensional and complex nature of public support for European

integration should thus receive much more scholarly and popular attention. In the following pages we provide the first in-depth examination of public support for different EU reform proposals across member states. Building on and extending existing work on public support for European integration that we outlined before, we have examined the trade-offs people make between different aspects of integration. Specifically, we focused on four dimensions of European integration:

- The functional dimension:

What type of European integration do EU citizens want? - The communal dimension:

With whom do EU citizens want this integration? - The utilitarian dimension:

How much are EU citizens willing to pay for this integration? - The institutional dimension:

How do EU citizens want this integration be governed?

These different dimensions capture the most important trade-offs that citizens face and are thus at the core of our data collection.

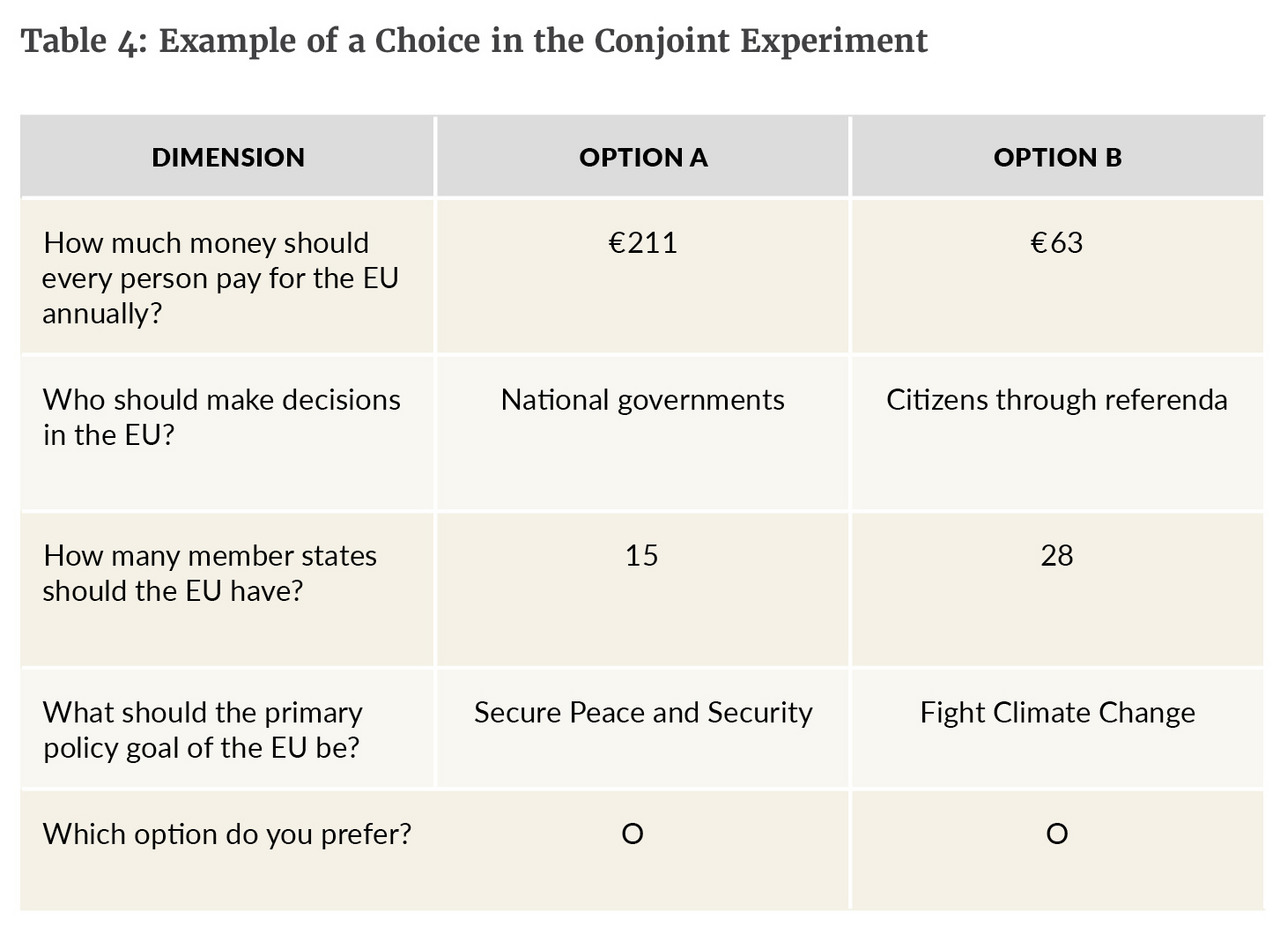

A Note on Understanding the Conjoint Experiment Results

In the conjoint experiments used here, we ask respondents to rank and rate five sets of two hypothetical choices, in this case reform proposals for the EU. These hypothetical choices have multiple attributes, that is to say they vary on four different dimensions of European integration outlined above. The goal here is to estimate the influence of each attribute of these dimensions (based on a linear probability or ordinary regression model) on the choices and ratings of the respondents for a given reform proposal. In order to make sure that alternative explanations are taken care of, we the use conjoint method based on a fully randomized design. So what does this mean exactly? Each respondent sees five sets of two different reform proposals that differ on the attributes of the functional, communal, utilitarian and institutional dimensions, and after each individual comparison, they are asked two questions: first, which proposal (A or B) do you prefer; and second, how would you rank each of the proposal. The ranking question was formulated as follows: “Please also evaluate each option individually. How likely is it that you would support ‘Option A’ / ‘Option B’ in a referendum? 1) very likely, 2) likely, 3) not likely, or 4) not very likely”. Table 4 below provides an example of one set of reform proposals that respondents were asked to choose between and rank.

The order in which the attributes of the different dimensions was presented was fully randomized. This allows us to assess the influence of different features of the reform proposals, costs or number of member states for example, on how respondents evaluate a given proposal relative to another. One of the advantages of randomizing the exact values for the different dimensions that feature on a reform proposal is that it is not necessary to rely on any assumptions about the functional form that maps reform proposal features on support (see Hainmueller, et al., 2014). Also, randomization ensures that the treatment groups are comparable with respect to alternative explanations, such as the way in which they interpret some of the information provided differently. The attributes of the different dimensions of the reform proposal are listed in Table 5 below.

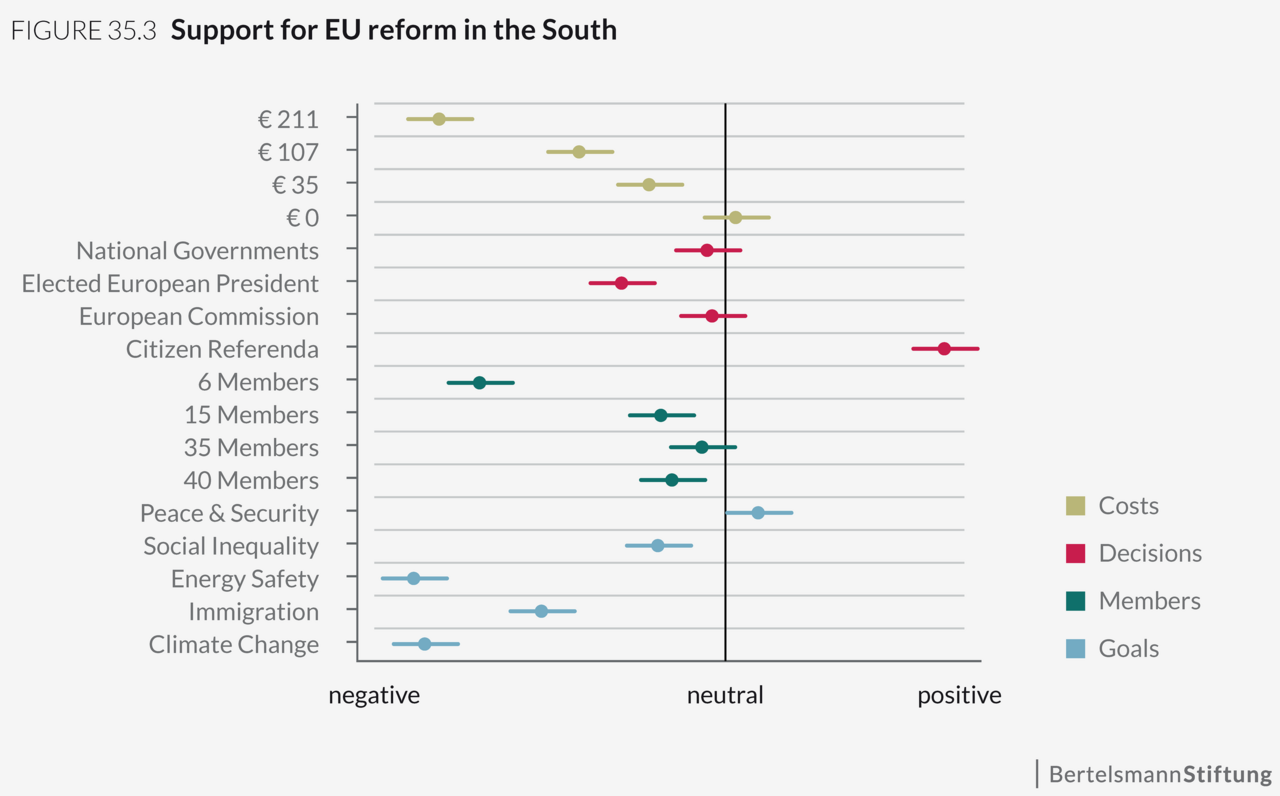

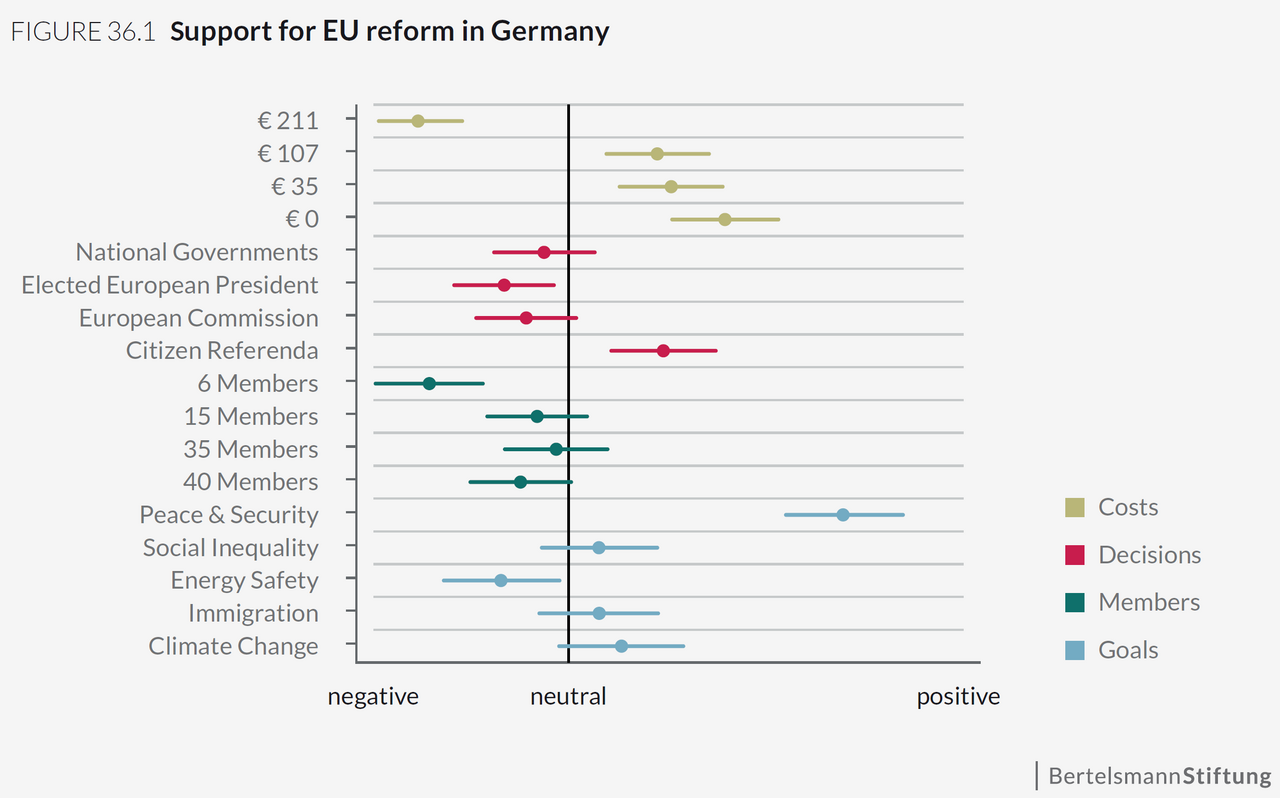

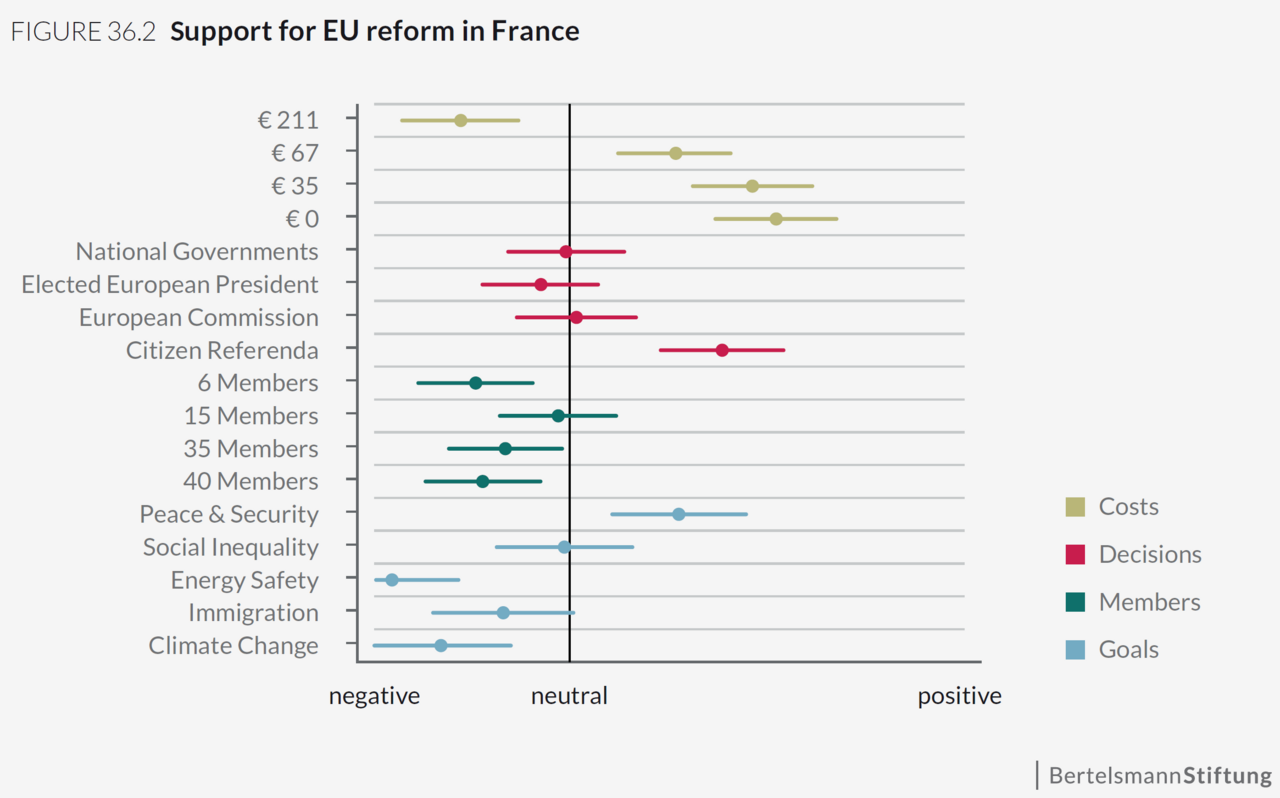

Interpreting conjoint results is less straightforward than the survey results presented in Part I, but really not difficult. As one can see in Figure 35, which presents the conjoint results for the EU28, the y-axis lists all the different features of each of the four dimensions: the utilitarian, institutional, communal and functional dimension. On the x-axis, the size of the effect of each attribute, for example 15 member states or a €35 annual contribution, on the choice for one of the two reform options is presented. If the effect of an attribute is large and positive then this attribute makes people prefer an EU reform proposal more, whereas if the size of the effect is large and negative it indicates that this attribute of the proposal makes people prefer an EU reform proposal less. Note that the sizes of the effects are always presented with reference to the current EU i.e., the status quo. That is to say, we present the effect of the different annual costs with reference to the average annual cost per capita (for the EU28 this is €0); the effect of different decision-making bodies with reference to the European Parliament making decisions; the effect of a different number of member states with reference to the current number of 28; and finally, the effect of different policy goals with reference to the promotion of economic growth. The thing that is important to take away from the graph is that if the size of the effect for a particular attribute, designated by the dot (the line around it provides the 95% confidence interval around the estimated coefficient), takes on a value greater than 0, people wish to see a change in the EU away from the status quo. When the size of the effect is smaller than 0, people prefer the status quo over the proposed reform.

If dots for an attribute are on the red line in the figures, this shows that people are indifferent about this reform and the status quo, while dots to the right of the red line indicate a preference for change away from the status quo, and dots to the left of the red line indicate a preference for the status quo rather than the proposed reform.

Support for EU Reform Proposals

Let us inspect support for EU reform in the EU as a whole (figure 34).

The results show that people desire two changes to the current status quo: namely that decisions are taken by referenda rather than by the European Parliament, and that the EU focus is primarily on peace and security issues rather than economic growth. People are indifferent about raising the average contribution to €35 in the EU compared to the current level of €0, and about national governments or the European Parliament making decisions. In terms of reforms that people oppose, we find that in terms of costs people do not want to contribute much more to the EU annual budget than €35 per capita per year. When it comes to decision-making, people are strongly opposed to the notion of an elected European President or the Commission taking decisions. They prefer the European Parliament doing so. In terms of membership, they strongly oppose a smaller Union, but interestingly are slightly less opposed to an EU with more member states, although they display a slight preference for the EU in its current size. Finally, people prefer an EU promoting economic growth over other policy goals such as securing energy safety, combating climate change or regulating immigration.

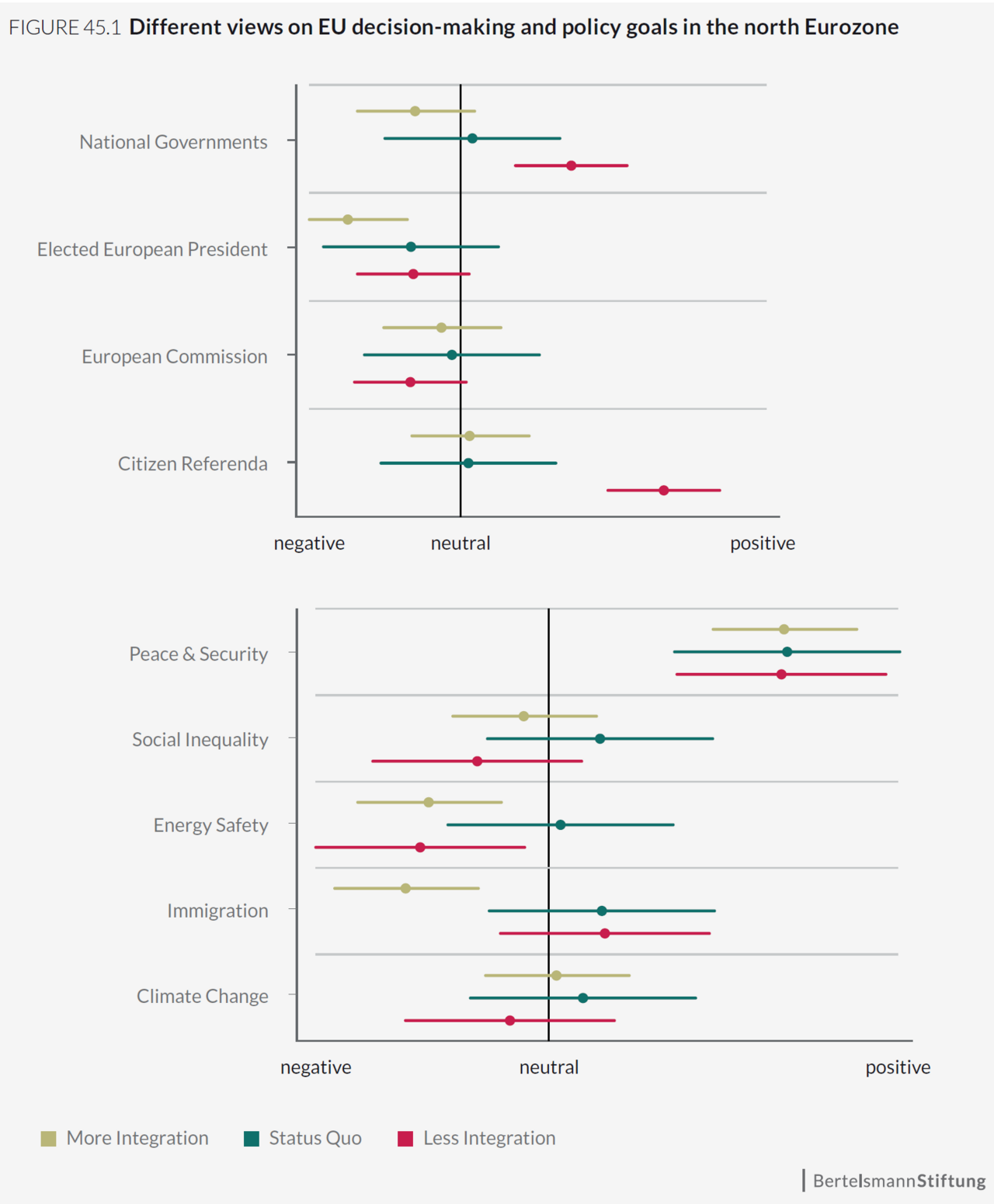

Overall, figure 34 provides us with a first peak into Europeans’ EU reform preferences and shows that making decisions by referenda and making the EU focus more on peace and security are important reform considerations for the average citizen. However, these results for the EU as a whole may mask important cross-national variation. Figures 35.1, 35.2, 35.3 and 35.4 present the same results, but split by region. The interpretation of these graphs is identical to that of figure 34 except for the fact that the reference point for the status quo when it comes to costs i.e., the annual per capita contribution to the EU budget, varies by region. For the North Eurozone (figure 35.1), the status quo is € 67, for the North Non-Eurozone € 107, for the South € 35, and finally for the East the average contribution per capita is € 0.

Figure 35.1 shows that citizens residing in the North Eurozone favour a Union that is slightly cheaper in terms of annual contribution per capita, even though the effects for € 0 and € 35 compared to the current level of € 67 are rather small. They clearly oppose an increase in the annual contribution to a level of € 107 or € 211. In terms of decision-making, they are indifferent about decisions being made by national governments or the Commission compared to the European Parliament, while they favour citizen referenda. As in the EU as a whole, citizens in the North Eurozone are far from enthusiastic about the notion of an elected European President making decisions. In fact, they clearly oppose it. In terms of membership, they clearly oppose a small EU of only six member states, while they are only slightly negatively inclined to an EU that comprises 15, 35 or 40 member states compared to the current 28. In terms of the policy goals that the EU should pursue, they strongly favour peace and security over economic growth even more so than was the case for the EU28, but an EU that focuses on social inequality, immigration and climate change is equally preferable to one that promotes economic growth. Citizens in the North Eurozone do prefer an EU that focuses on economic growth over one whose primary concern is energy safety.

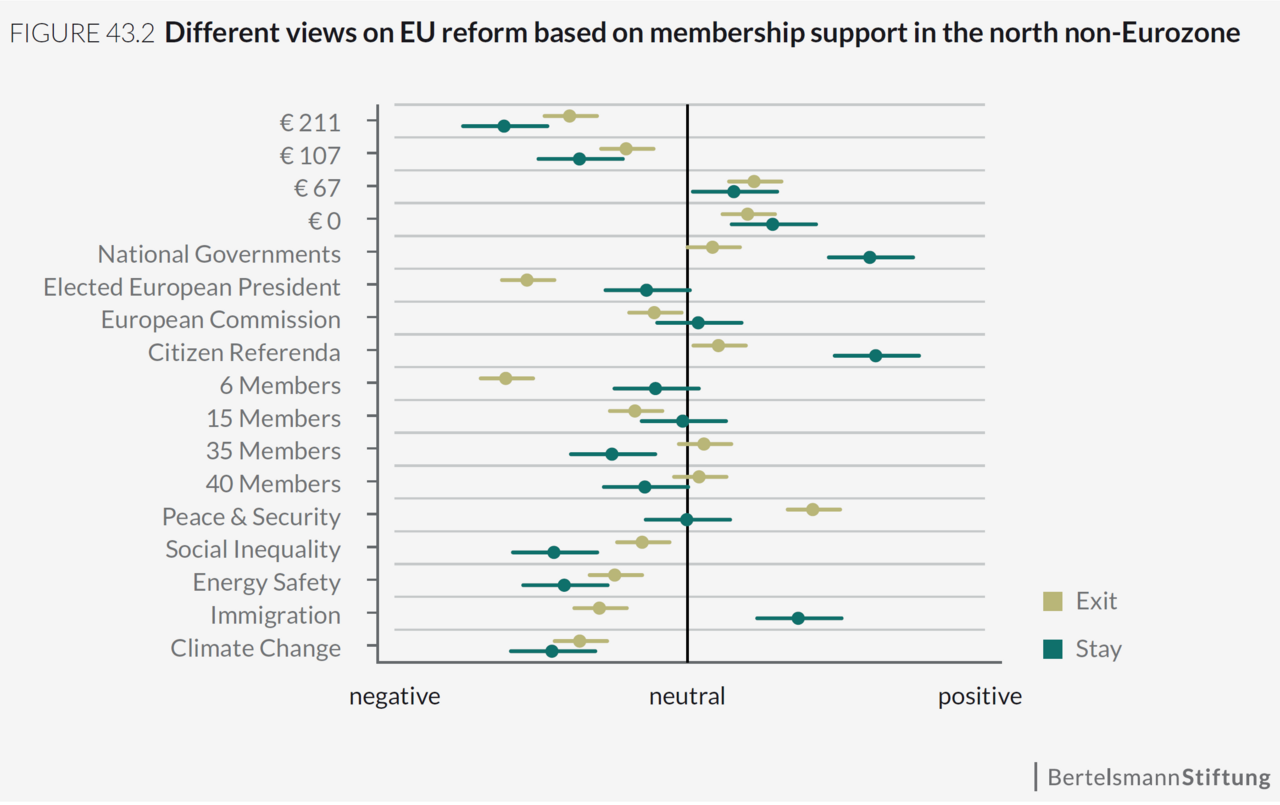

Turning to citizens in the North non-Eurozone (figure 35.2), the British, Danes and Swedes display similar reform preferences compared to their counterparts in the North Eurozone, expect for their decision-making and policy preferences. Contrary to citizens in the North Eurozone, British, Danes and Swedes are much more in favour of decisions taken either through citizen referenda or by national governments. They seem wearier of EU institutions making decisions, especially were it to be an elected European President. In terms of policy goals that the EU should pursue, peace and security are highest on their agenda, followed by economic growth and immigration (on the latter points, the British, Danes and Swedes are indifferent.) Contrary to the North Eurozone citizens, however, they would be less in favour of an EU focusing on social inequality and climate change.

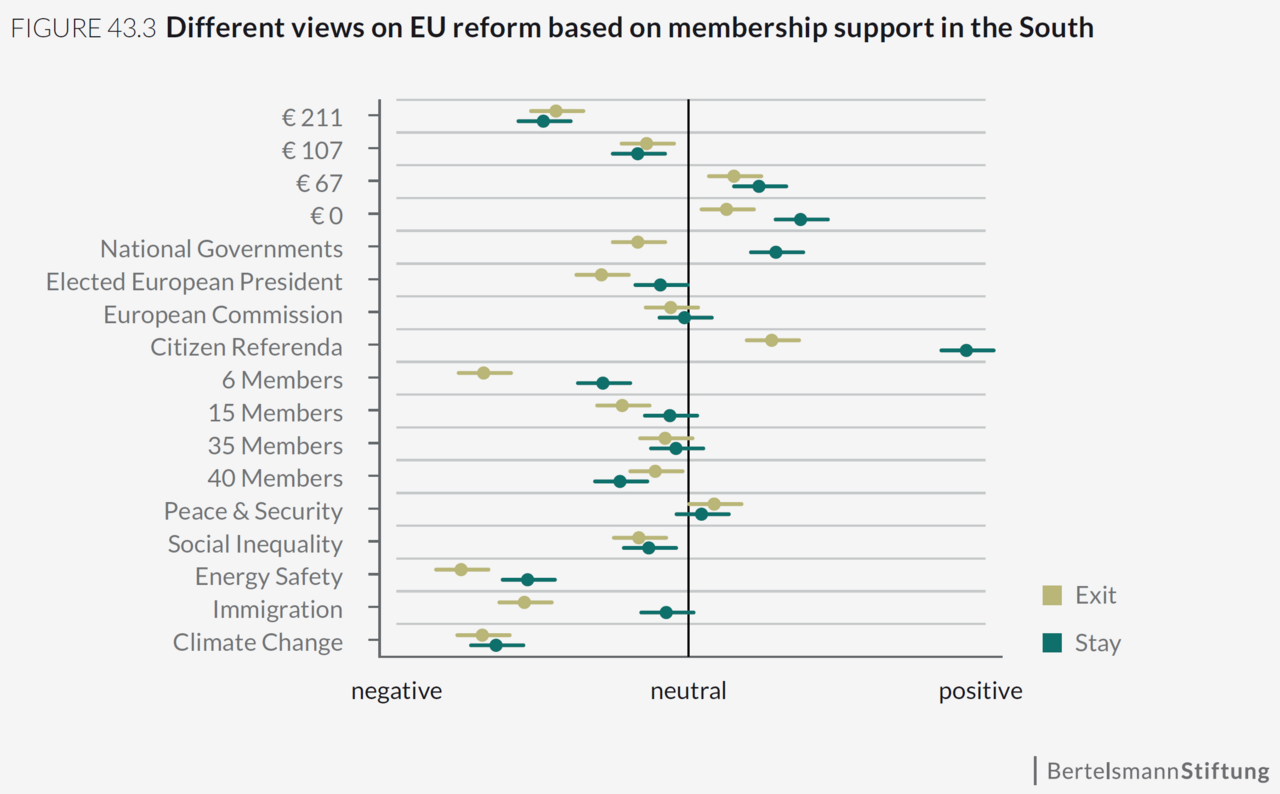

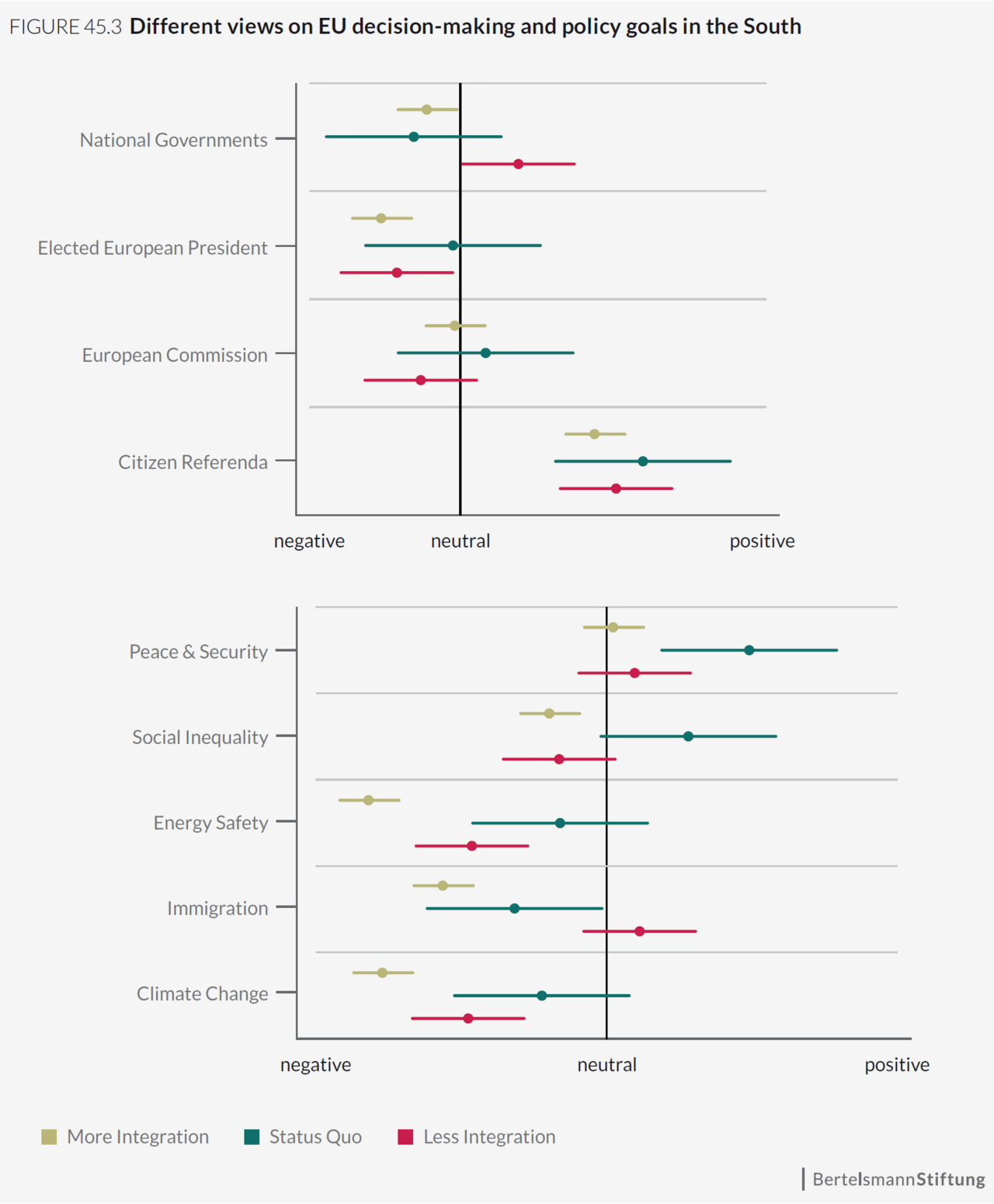

In the South (figure 35.3), we find that citizens’ strongest preference for change relates to citizen referenda; these are much preferred over decision-making by the European Parliament. Like citizens in the North, they prefer an EU that is cheaper, and oppose a smaller versus a larger EU in terms of member states. When it comes to policy preferences, they differ from the North in that they are indifferent about an EU that focuses on economic growth or one that prioritizes peace and security. Given that the South was hit hard by the Eurozone crisis, a strong preference for an EU that promotes growth should not come as a surprise.

The final region we consider is the East and these results feature in figure 35.4. People in the East display even more differences from the North than we found for the South. Interestingly, they are willing to do more for the EU than they currently do, paying even up to € 107 a year. This pattern deviates from all other regions where citizens are not willing to pay more. Citizens in the East, like those in the North Non-Eurozone, are weary of EU institutions taking decisions, especially a directly elected President. They favour citizen referenda but are indifferent about national government vis-à-vis the European Parliament. They strongly oppose the idea of a smaller EU, and are indifferent about an EU with 28 versus 35 or 40 member states. Finally, like the South, Central- and East- European citizens are most supportive of an EU that deals with economic growth or peace and security, these policy goals are much more preferred to policies like combating climate change or regulating immigration.

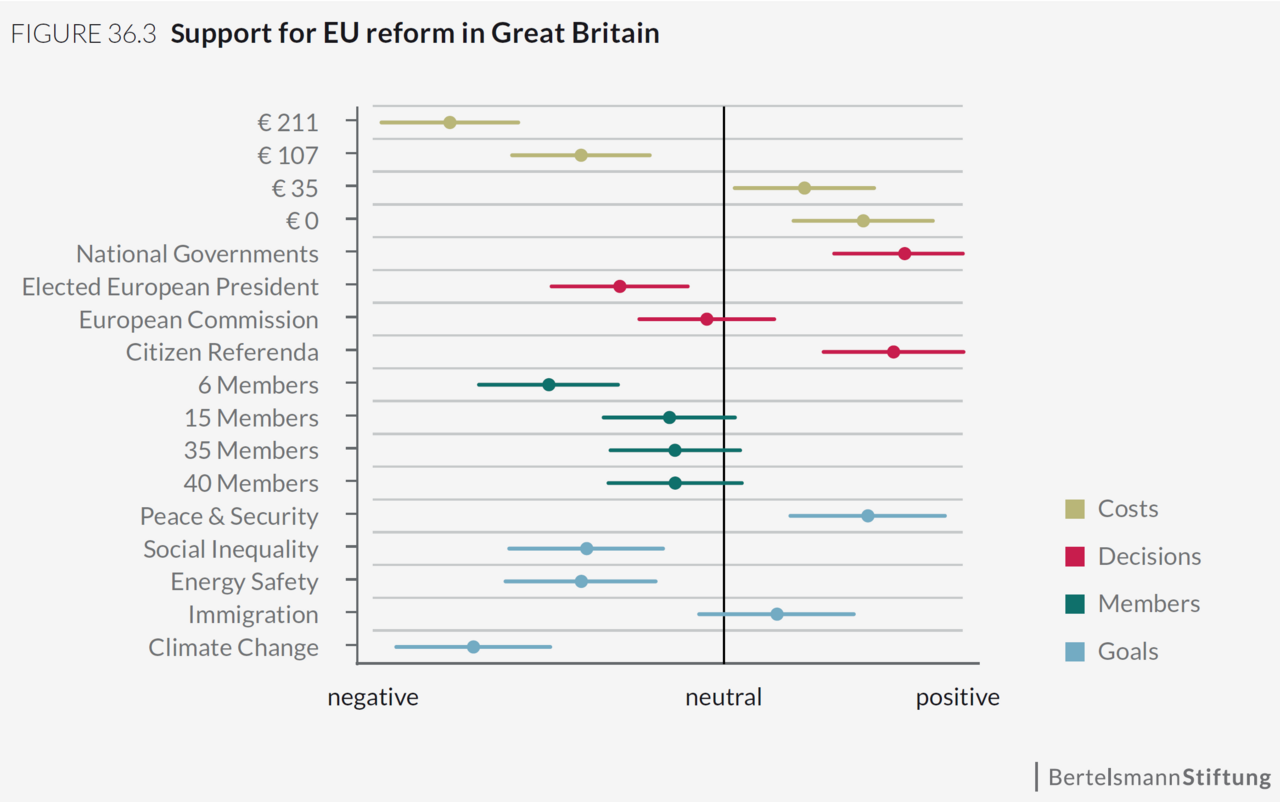

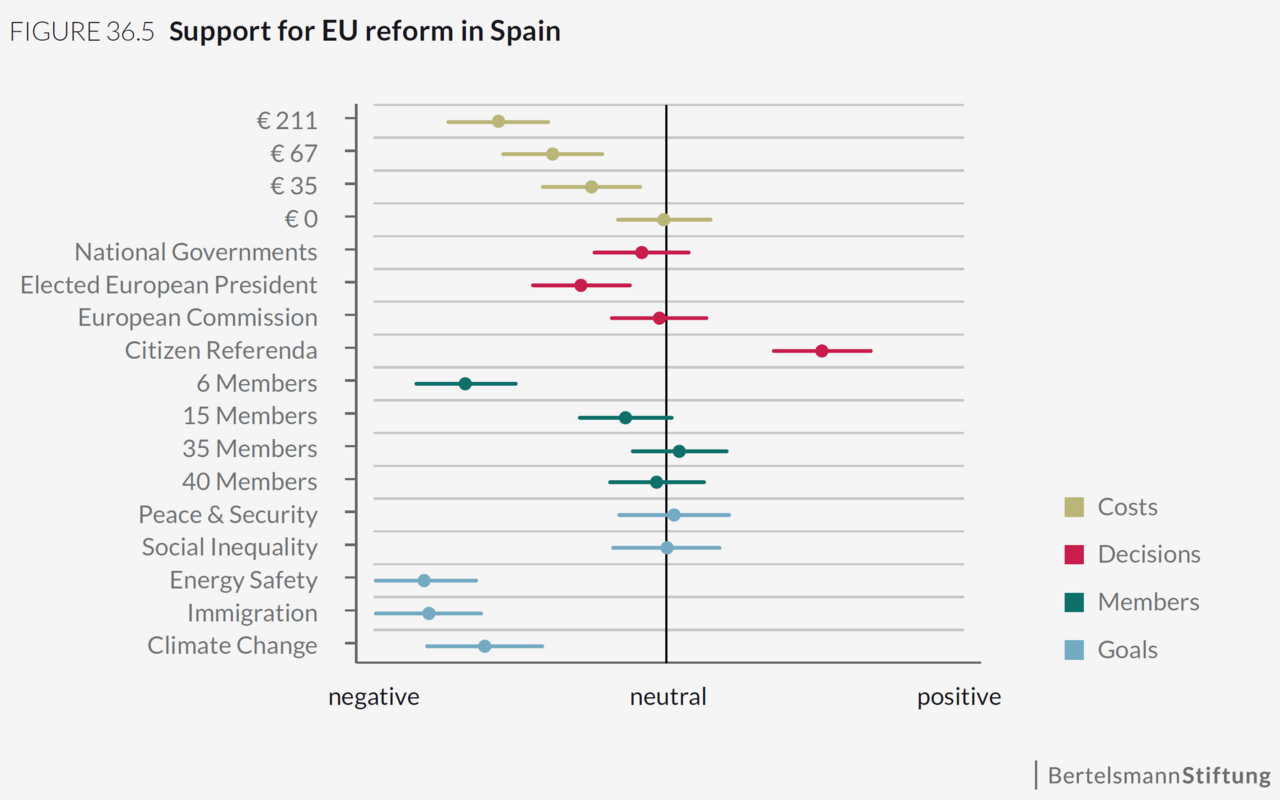

How are EU reform preferences distributed across the six big member states? Figures 36.1, 36.2, 36.3, 36.4, 36.5 and 36.6 show the results of the conjoint experiment in Germany, France, Great Britain, Italy, Spain and Poland, respectively.

In Germany (figure 36.1), we find that people prefer an EU that is cheaper, and are equally favourable about the prospect of an EU that would have 15, 35 or 40 member states compared to 28. Germans most strongly differ from the EU as a whole in terms of their decision-making or policy preferences. They support decision-making through referenda compared to the European Parliament, but are equally happy with an EU in which decisions are made by national governments or the Commission. Interestingly, they also seem much less opposed to the idea of a directly elected EU President compared to citizens in the EU as a whole. In terms of policy, German citizens strongly favour peace and security as the EU’s main policy goal. Peace and security is preferred over economic growth, but except for slight opposition to energy safety, Germans are indifferent between other goals, such as immigration, climate change or social inequality.

French opinion resemble the Germans’ in many respects. But more than the Germans, the French are indifferent about the European Parliament making decisions or a directly elected EU President (figure 36.2). This might reflect their national experience with an elected President. Like the Germans, however, the French do favour decisions being made via citizen referenda, but are indifferent about national governments or an EU institution taking decisions. The French favour the current number of member states over a smaller or larger EU. In terms of policies, they differ slightly from the Germans in that they favour an EU that addresses social inequality, immigration and economic growth to an equal extent.

The British hold different opinions about EU reform compared to the Germans and French (figure 36.3). They differ mostly in terms of decision-making preferences as they clearly favour decisions being made by national governments or via EU referenda rather than by the European Parliament. These effects are quite substantial. This British preference for decision-making by national governments is clearly different from the overall EU pattern. In terms of preferred policy goals, they are, like the Germans, in favour of peace and security, followed by immigration and economic growth.

Figure 36.4 shows the results for the Italian representative sample. The Italians like the British, Germans and French favour a cheaper EU compared to their current contribution of € 107 per capita, and want an EU that comprises more than six member states. They, like the citizens in the EU as a whole, favour citizen referenda, and oppose a directly elected EU President. Contrary to the British, Germans and French, however, Italian citizens are strongly in favour of an EU that promotes economic growth, slightly more so than peace and security and immigration.

The results for Spain, which are displayed in figure 36.5, show that like the Italians, Spanish citizens strongly favour citizen referenda over EU decisions being made by the European Parliament. They also favour a bigger EU with at least six member states. Like the Italians, they support an EU reform proposal more when it is focused on promoting economic growth, yet contrary to the Italians they favour growth equally to social inequality and peace and security. Interestingly, in terms of annual costs, Spaniards seem to be willing to pay a bit more for the EU than they currently do. They are equally supportive of a reform proposal that would mean paying € 35 compared to their current € 0 (they are a net recipient).