Britain’s recent departure from the EU showcases what can happen when dissatisfaction with the EU and its perceived lack of democracy reaches an extreme. Our latest poll of the 27 member states of the European Union plus the UK paints a more positive picture of the health of European democracy. The survey, conducted by eupinions for the Oxford University Europe’s Stories research project in December 2020, suggests that there is strong support for the European Parliament, with four out of five Europeans believing that it is important to have a supranational parliament. We also show that most Europeans believe that EU membership has brought them personal benefits, particularly in the form of freedom of movement. This reflects strong support for freedom of movement found in previous polls, including a 2018 Eurobarometer poll which showed four in five Europeans to be supportive of free movement in the EU.

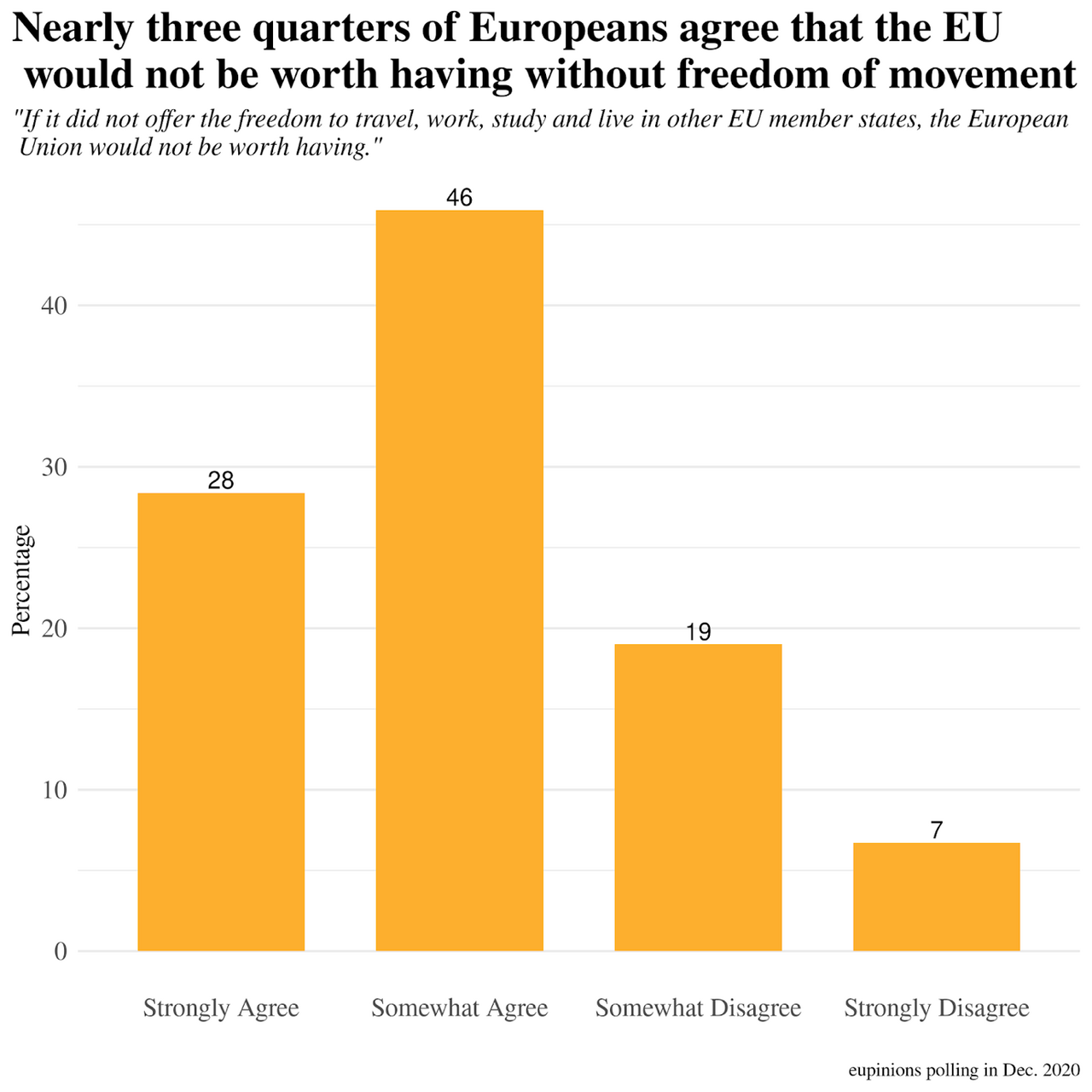

Our most striking finding goes beyond confirming the popularity of freedom of movement in Europe, asking respondents whether the EU would be worth having without freedom of movement. The responses show that freedom of movement is so important to Europeans that nearly three quarters (74%) of respondents say that the EU ‘would not be worth having’ without it.

Concerning the central democratic institution of the Union that provides this benefit, our poll reveals substantial support for the European Parliament’s existence. But we also find that most Europeans believe the existence of the Parliament to be of secondary importance, compared with the importance of the actual policy outcomes that are delivered. Additionally, our respondents are slightly more likely to think of national leaders, like Merkel and Macron, when prompted by the term ‘European leaders’, rather than the institutional heads of the EU like Ursula von der Leyen. And only one in five respondents (21%) correctly identified the person who gives the EU’s State of the Union - that is, the President of the European Commission.

In sum, our respondents appear more concerned about what political scientists term ‘performance legitimacy’ (legitimacy deriving from the policy outputs of an institution) rather than ‘procedural legitimacy’ (legitimacy deriving from the political process by which they are reached). We think that there may be an important lesson here for the planned Conference on the Future of Europe. Europeans are much more interested in what the EU does for them, what it actually delivers, than in how exactly it does it - and least of all in the intricacies of institutional reform.

What are the most important things the EU has done for you?

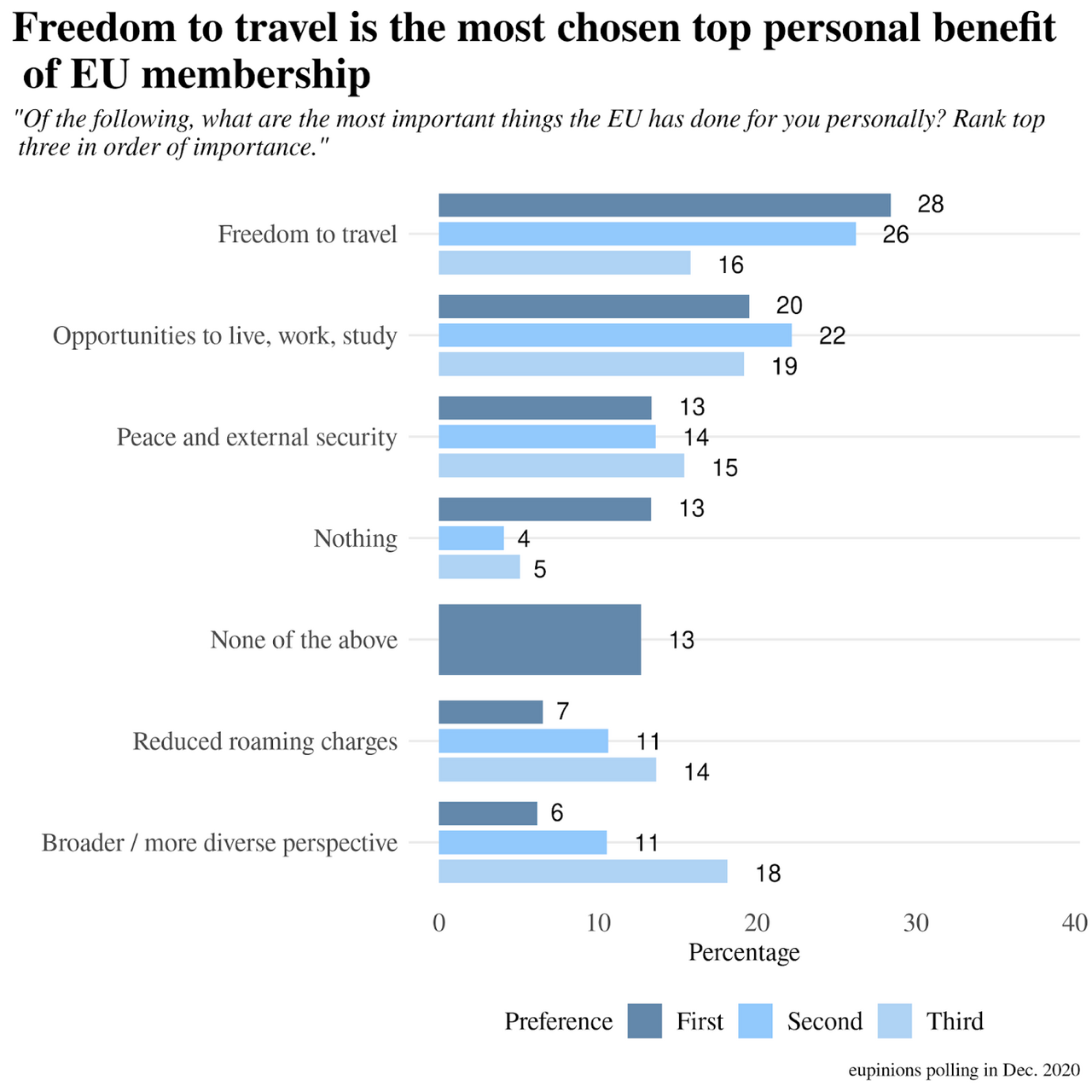

Our first question asked respondents to rank the top three most important things the EU had done for them personally from a set of options. The results show that freedom of movement is the single most important benefit of the EU for respondents in our survey. Freedom to travel was the most selected option as the first choice (28%) and as a second choice (26%), and was followed by opportunities to live, work and study in Europe (20% first choice, 22% second choice). The next most popular response was peace and external security, which was the first choice among just 13% of those taking our survey. The benefits of ‘broader perspectives’ and reduced mobile roaming charges were the least popular of our options, both selected by less than a tenth of respondents as their first choice and both receiving fewer first choice responses than ‘the EU has done nothing for me personally’.

The answers to our ranking question may also reflect a moderate level of Euroscepticism felt within our sample, with 13% of respondents reporting as their first choice that the EU had done nothing for them personally. The same proportion also selected ‘none of the above’.

Figure 1

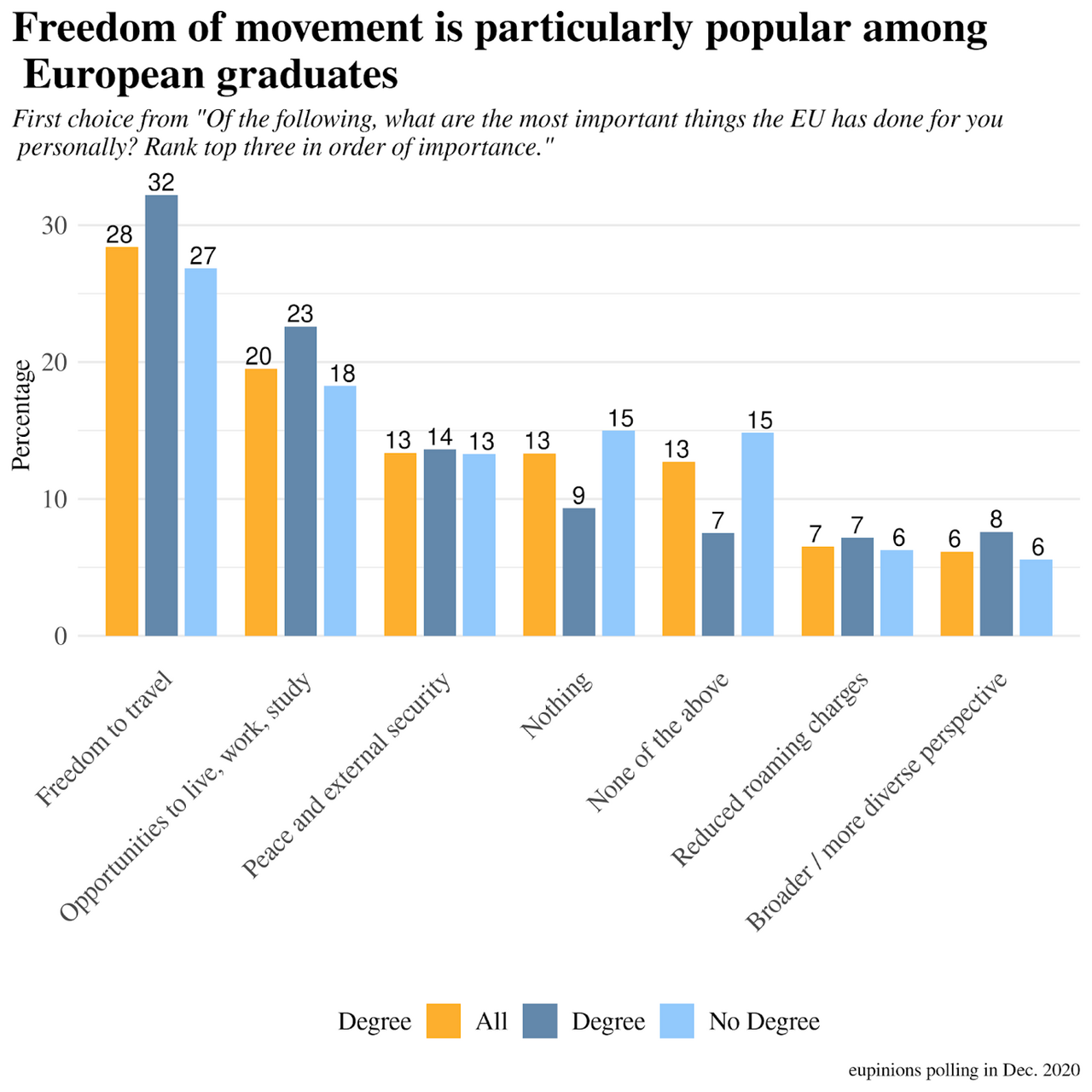

Looking at the breakdown of these choices by demographics, both the right to travel across borders and the right to settle in other countries were chosen more often by individuals with university degrees than those without, and graduates were also much less likely to report that the EU had done nothing for them or to select ‘none of the above’.

Figure 2

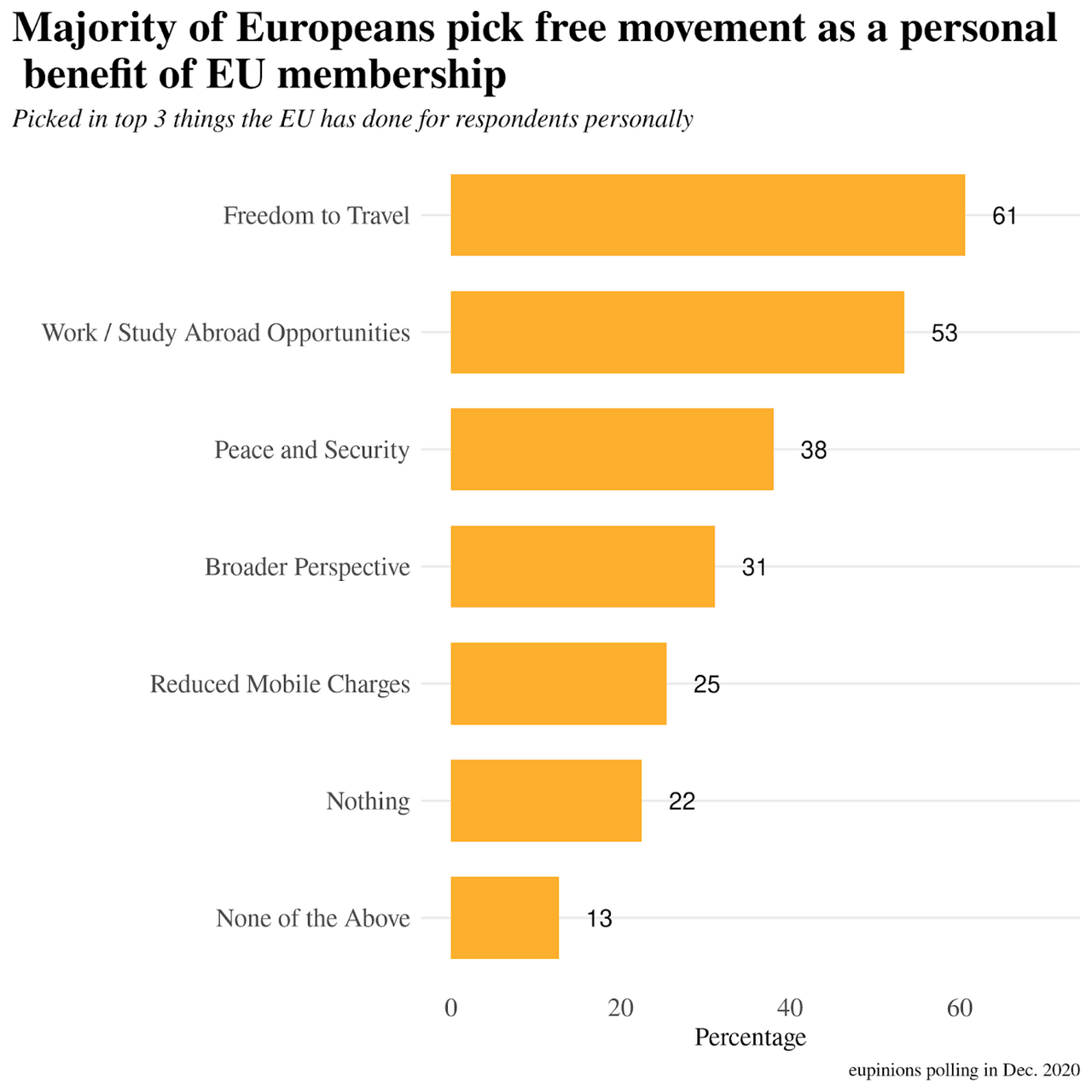

Indeed, freedom to travel and opportunities to live, work and study in EU countries were cited by more than half of respondents as one of their top three EU personal benefits (we exclude responses that came after an individual stated that the EU had done nothing for them). ‘None of the above’ and ‘the EU has done nothing for me personally’ were only selected by 14% and 22% of the sample respectively. Note that, because respondents could select three responses for their top priorities, the percentages for choosing a benefit as in their top three do not add up to 100.

Figure 3

To better understand the importance of freedom of movement to our surveyed individuals, we asked the extent to which respondents agreed with the statement “if it did not offer the freedom to travel, work, study and live in other EU member states, the European Union would not be worth having”. Three quarters (74%) of respondents agreed with this statement, demonstrating that freedom of movement is close to the heart of the European project for most Europeans. While responses to this question were similar across demographic groups, there was some difference between countries, for example with those in Poland most likely to disagree with the statement.

Figure 4

European Parliament

We were interested in establishing how far our respondents cared not only about the benefits brought by the EU, but also the processes by which they are brought about. In a global context of increasing dissatisfaction with democracy, we investigated whether Europeans think the European Parliament is an important part of European democracy.

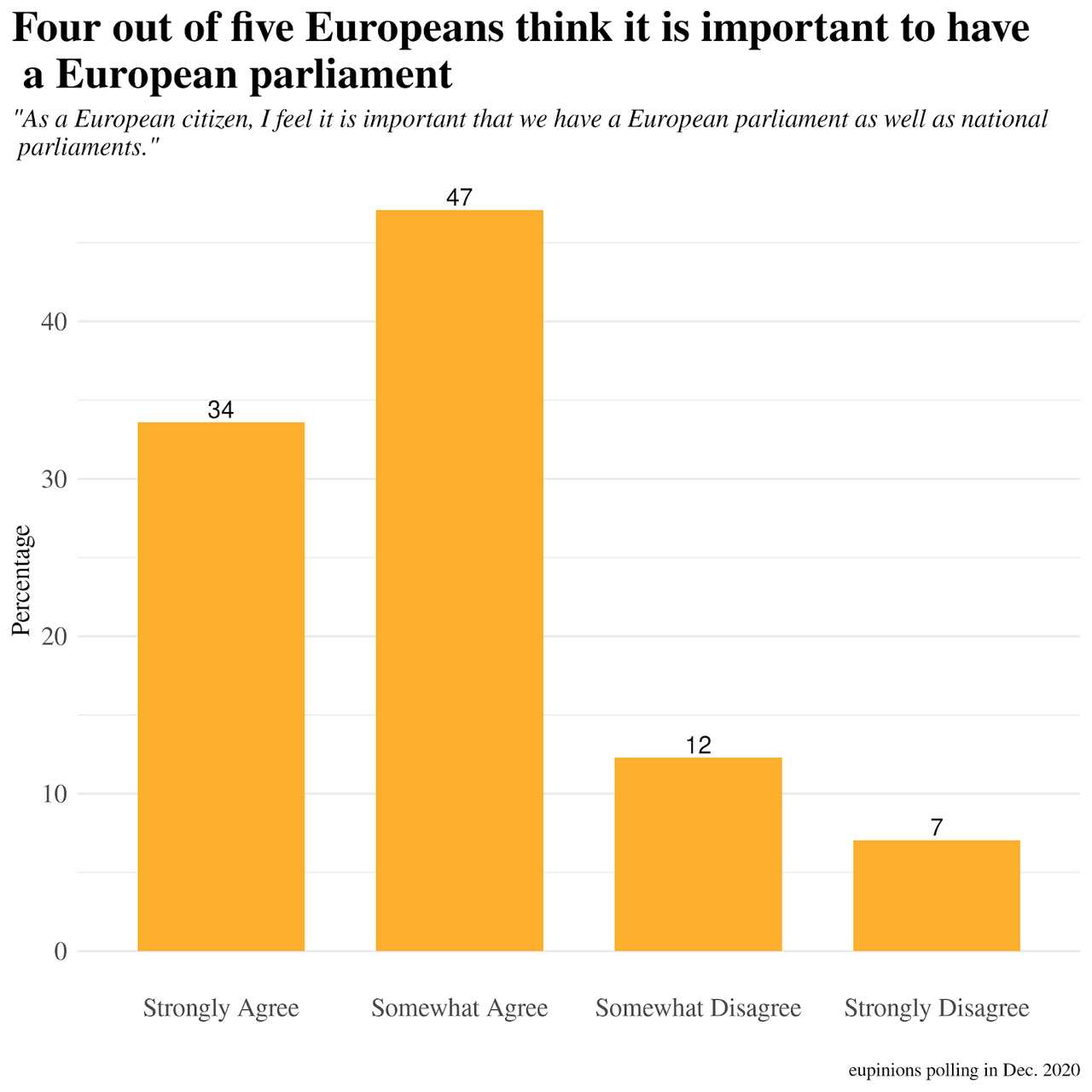

To assess attitudes towards the European Parliament, we asked respondents the extent to which they agreed with the statement “as a European citizen, I feel it is important that we have a European Parliament as well as national parliaments”. Our respondents from across the EU overwhelmingly agreed with this statement (81%), with a third (34%) strongly agreeing, and only 7% strongly disagreeing. In the wake of Brexit, this suggests that concerns about sacrificing national parliamentary sovereignty is not widespread across the EU. Strong agreement with the need for a European Parliament was particularly high in Germany and Spain, but there was little difference between respondents according to age, gender or education. (Note that there is a small distortion of the results due to the inclusion of the UK in our sample, with British citizens of course no longer being European citizens.)

Figure 5

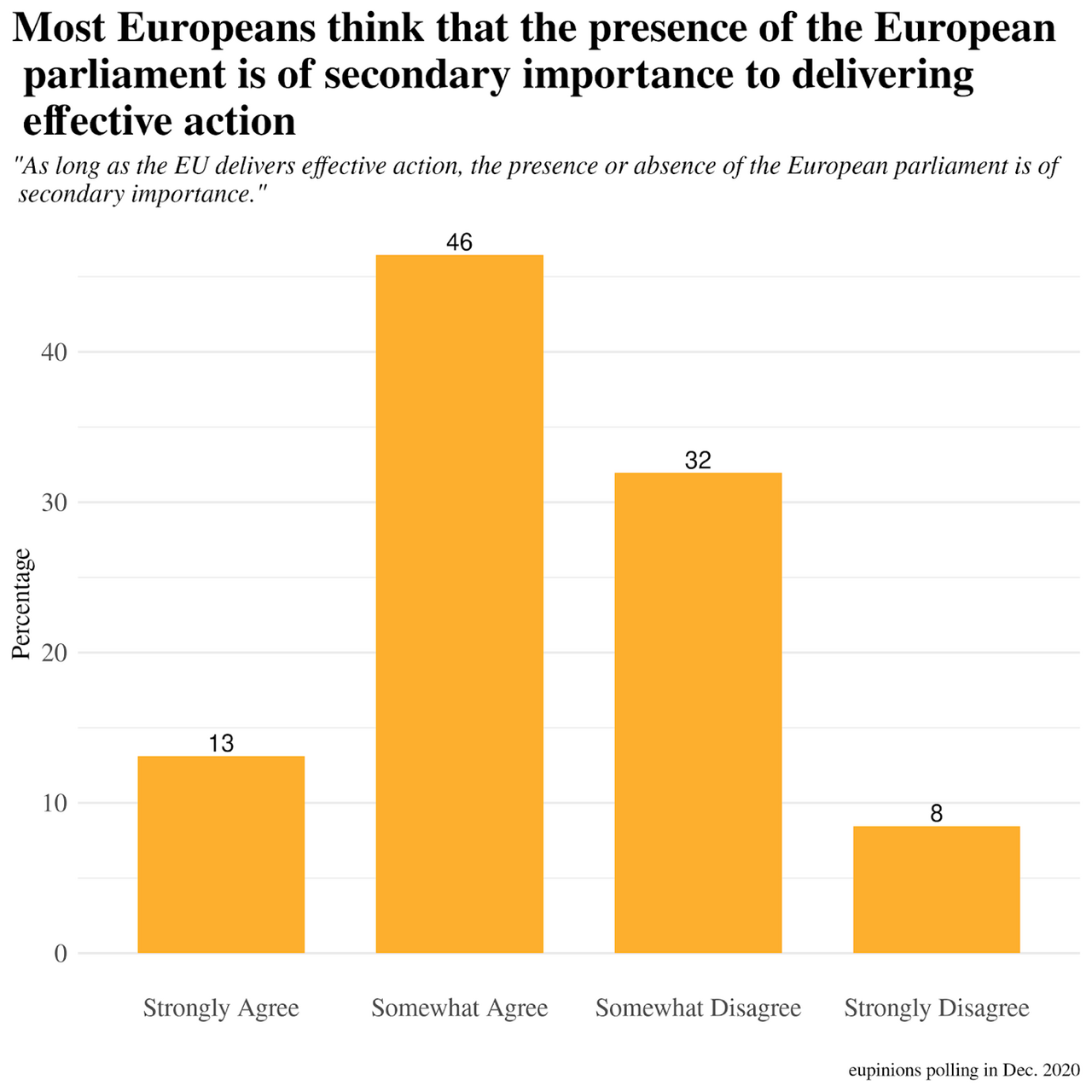

However, this initial enthusiasm for the European Parliament appears to come second to a desire for ‘results’, rather than the process by which they are reached. When prompted with the statement “as long as the EU delivers effective action, the presence or absence of the European Parliament is of secondary importance”, 59% of our respondents agreed with the statement. Three in five of those who previously agreed that it was important to have a European Parliament agreed with the statement, suggesting that even those who believe a European Parliament is important are still more focussed on the effectiveness of its policymaking than just its existence. Individuals with university degrees tended to agree slightly more that the European Parliament is of secondary importance to effective action, but there is otherwise little difference by demographics like age or nationality.

Figure 6

European Leaders

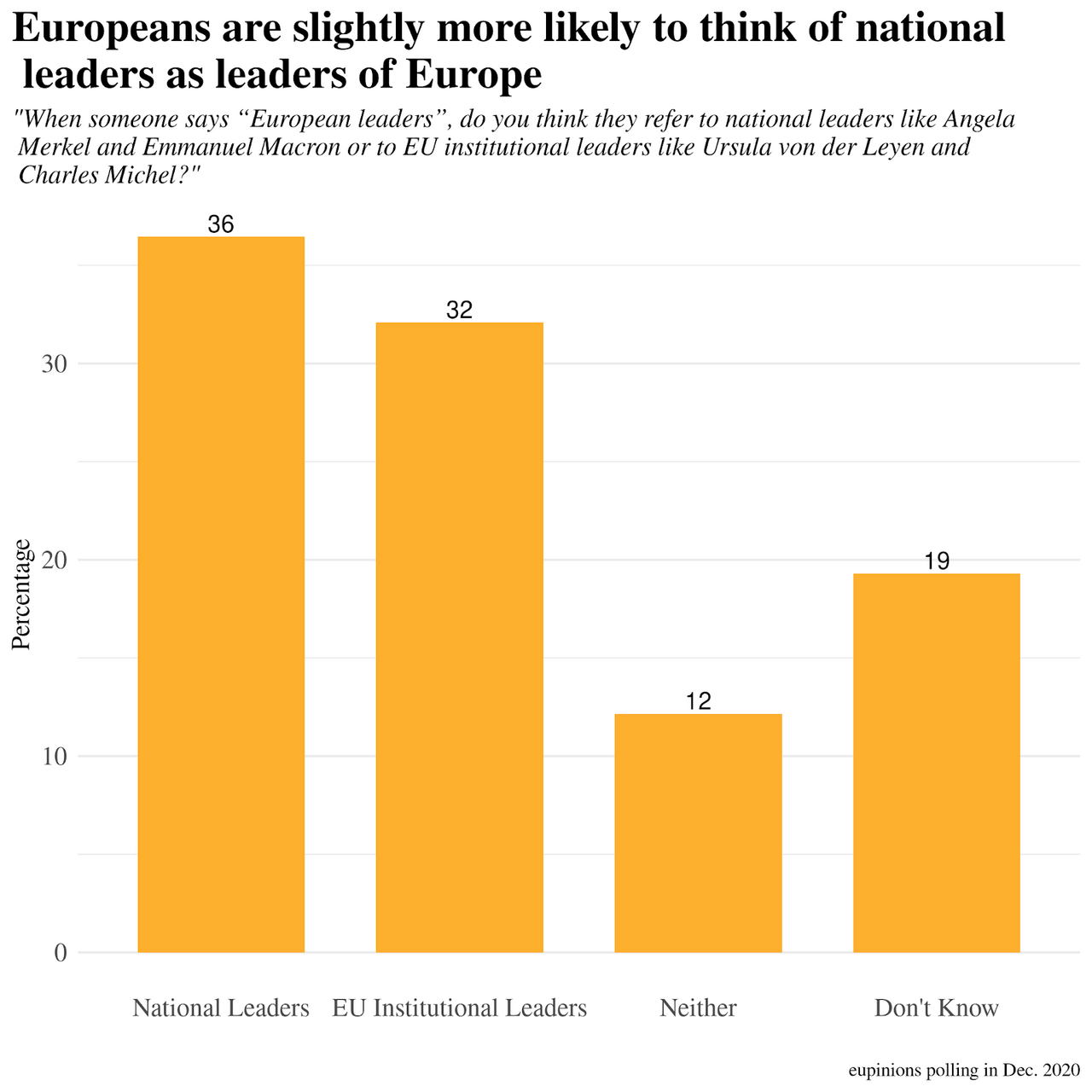

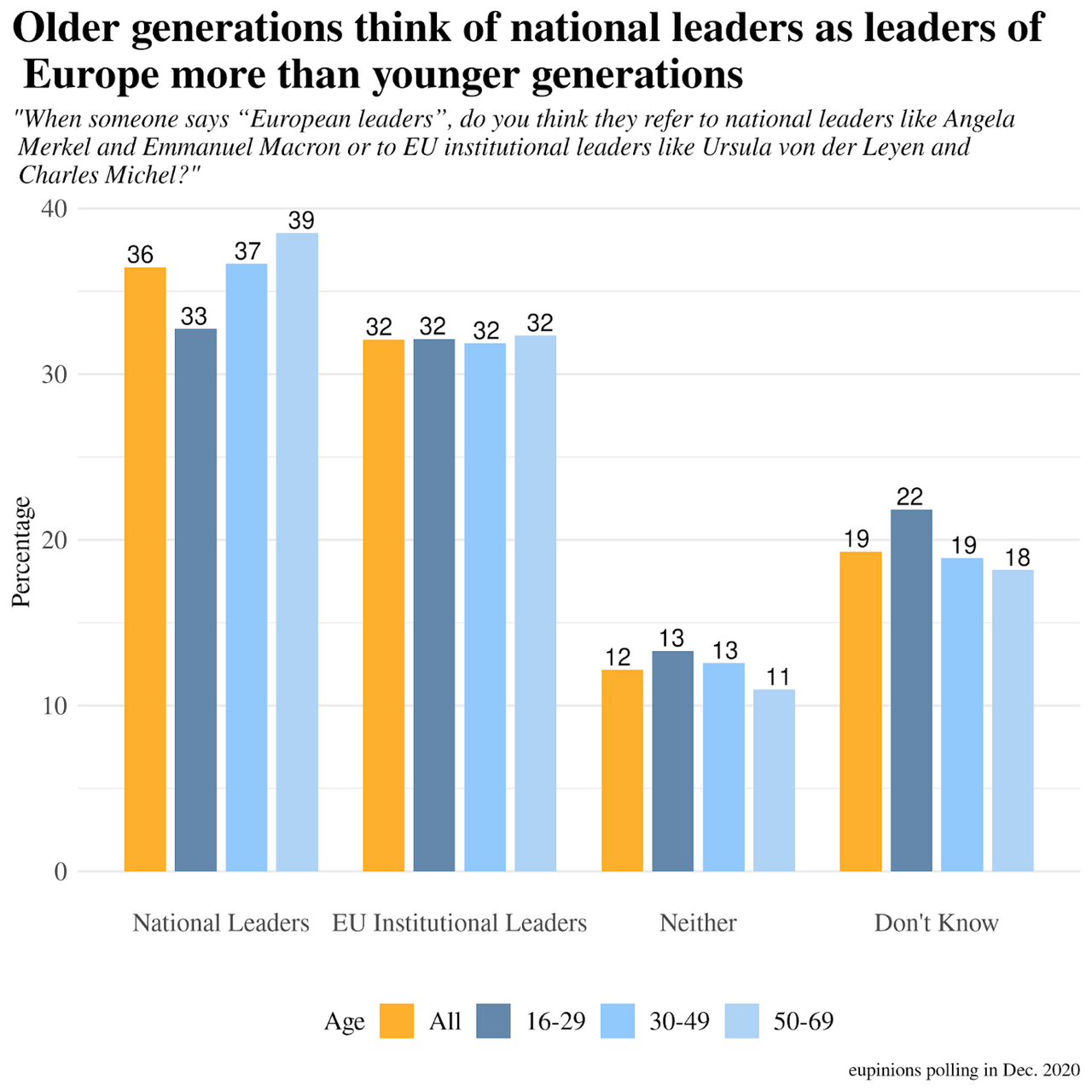

To investigate further the relationship between the Union’s supranational and national level governments, we asked respondents who they think is referred to by the term ‘European leaders’: national leaders, EU institutional leaders, or neither. National leaders was narrowly the most popular choice at 36%, compared to 32% for EU institutional leaders. Many respondents reported that they did not know (19%) or would think of neither (12%). While a similar proportion of all age groups referred to EU leaders in answer to our question, older age groups were more likely to report thinking of national leaders in response to the question, while young people were more likely to think of neither sets of political leaders or to select ‘don’t know’.

Figure 7

Figure 8

Again there were some slight discrepancies between different countries when answering the question above. Residents of Poland and the Netherlands were far more inclined than residents of other countries to interpret ‘European leaders’ as national leaders like Angela Merkel and Emmanuel Macron, whilst respondents in Belgium and Spain were actually more likely to think of EU institutional leaders like Ursula von der Leyen and Charles Michel rather than national leaders.

Differences across other demographics tended to reflect differing tendencies to select ‘don’t know’ or ‘neither’, rather than national leaders against institutional leaders. Respondents with degrees, for example, were more likely to select national leaders or EU leaders than ‘neither’ or ‘don’t know’ but, in line with the rest of our respondents, they were still more likely to pick national leaders than EU leaders.

To check whether the above responses simply reflected an individual’s knowledge of European leaders, we also asked respondents which senior EU figure gives an annual State of the Union address. Unsurprisingly, those who correctly answered with ‘The President of the European Commission’ were substantially more likely to express a preference for who they think is referred to by the term ‘European leaders’, with just 8% selecting ‘don’t know’ (compared to 22% in the rest of the sample). Again, however, they were slightly less likely to select EU institutional leaders over national leaders, despite their better knowledge of the workings of the EU.

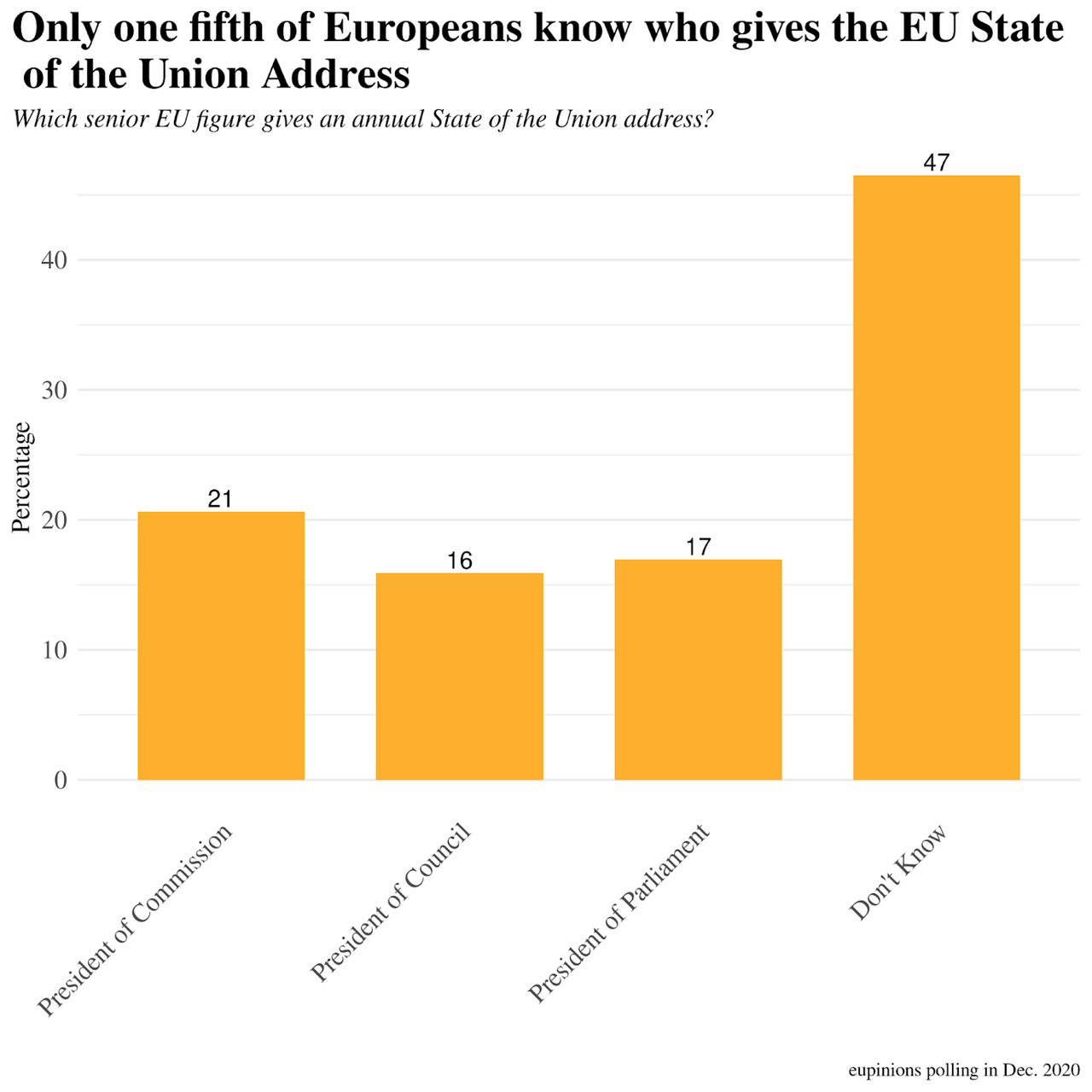

Responses to the knowledge question itself were predictably poor - nearly half of our respondents admitted that they didn’t know the answer, whilst only around a fifth (21%) selected the correct answer (President of the Commission). The remaining third of our respondents were split fairly equally between the two incorrect answers (President of the Council and President of the Parliament). This shows generally low knowledge of the role of EU institutional leaders in our sample, a stark finding given that all politics surveys tend to over-sample the most politically knowledgeable in society.

Figure 9

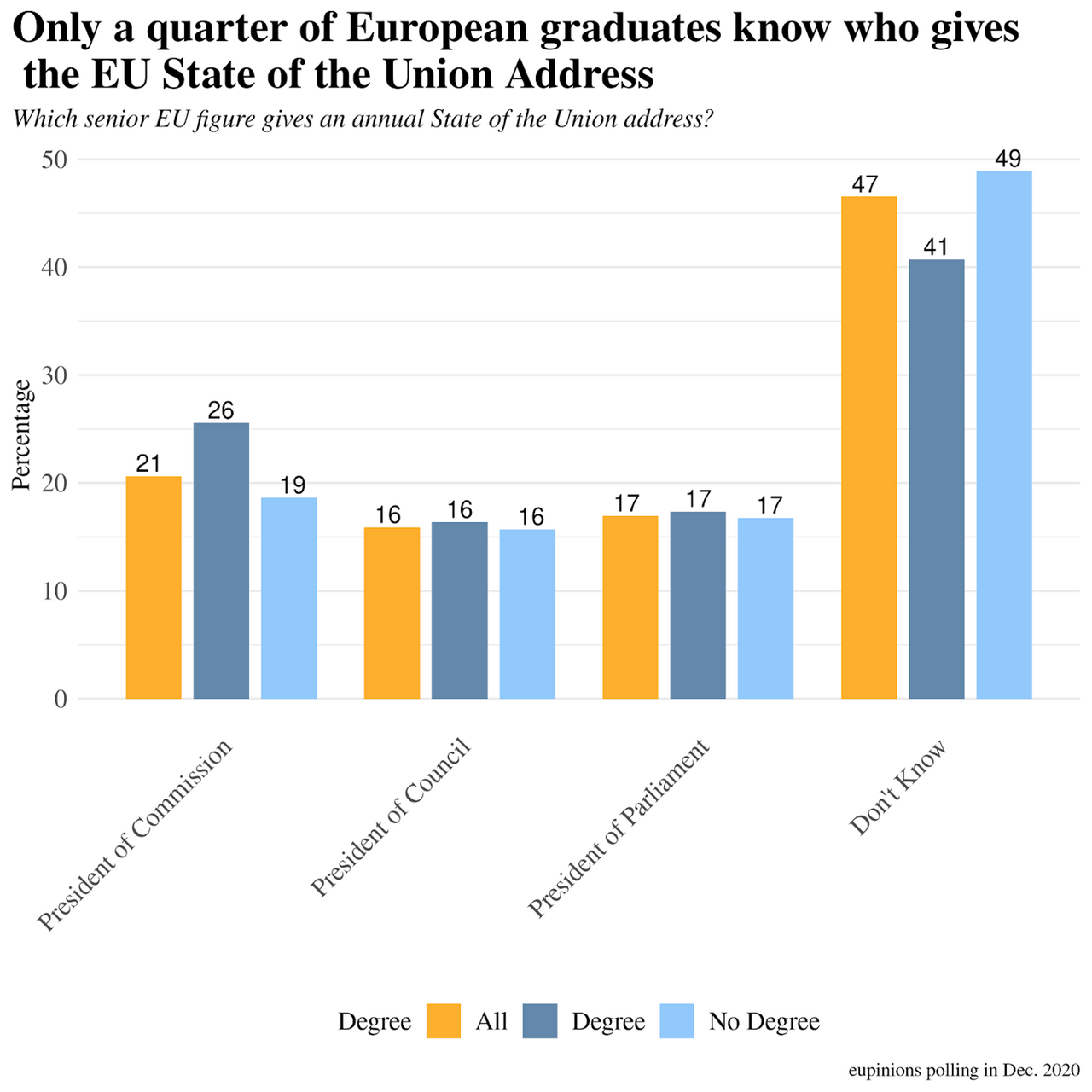

Education does make some difference to increasing the likelihood of selecting the correct answer, with 26% of university graduates correctly identifying this as a role of the President of the European Commission. However, graduates and non-graduates selected the wrong answers at fairly equal rates, and so while graduates did select the correct answer more, they were also simply less likely to answer that they didn’t know.

Figure 10

In line with answers to our last question, women were more likely to admit that they didn’t know, whilst men were more likely to give a firm answer, both correctly and incorrectly. Across countries, the correct answer was given most often by Italians (25%), Belgians (22%) and Spaniards (22%).

Methodology Note

The sample with a size of n=13,215 was drawn by Dalia Research from 01/12/2020 to 20/12/2020 across all 27 EU Member States plus the UK, taking into account current population distributions with regard to age (14-69 years), gender and region/country. In order to obtain census representative results, the data were weighted based upon the most recent Eurostat statistics. Any references to differences between countries in the report pertain only to the six countries with sufficiently large sample sizes, namely: Belgium, Germany, France, Italy, The Netherlands, Poland and Spain. Calculated for a sample of this size and considering the design-effect, the margin of error would be +/-1.1 % at a confidence level of 95 %.

----------

The authors are members of the Europe's Stories project research team of the Dahrendorf Programme for the Study of Freedom at St Antony's College, Oxford University. This poll was part of a collaboration between that project and eupinions. Europe's Stories is funded by the Mercator foundation, the Zeit foundation, and the Friedrich Naumann foundation.