Executive Summary

For politicians across the globe, the COVID-19 pandemic is a stress test for governance. Curbing the coronavirus pandemic calls for swift and strong executive action. Indeed, many government leaders have resorted to extraordinary and, in some cases, draconian measures, which include placing restrictions on individual movement, introducing physical distancing requirements, and mandating businesses to close. And while lockdown measures across the EU clearly derive from public health needs, they also open up avenues for states to place further restrictions on fundamental democratic rights. Current measures run the risk of allowing leaders to engage in more lasting executive overreach and thus undermine key liberal democratic norms in society.

In some EU member states, we have seen protests and unrest in the streets, as well as the outright rejection among some citizens of the virus’s existence and the health threat it poses. Balancing the duty to protect public health with the right to dissent and protest is no easy task for any state actor and has potentially long-term implications for public trust in government action. Concerns about pandemic-related democratic backsliding and the risk of weakening public support for appropriate measures underscore the importance of examining how European citizens view democracy and the rule of law. In this report, we examine not only how European citizens evaluate the state of democracy in their country and the EU more generally, but also what they think characterizes a good democracy.

This report addresses three questions regarding EU citizens’ perceptions in this regard:

- What are the most important characteristics of democracy?

- How well does democracy function in their own country and in the EU?

- To what extent do they trust their country’s government or the EU with regard to delivering an effective response to the COVID-19 pandemic?

This report seeks to answer these questions by presenting evidence based on a survey conducted in December 2020 in which we interviewed just under 12,000 citizens across the EU. In doing so, we present two sets of data. One for the European Union as a whole, another for seven individual member states (i.e., Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland and Spain).

The results can be summarized as follows:

- Within the EU27, citizens attach great importance to rule-of-law issues when it comes to democracy. The importance of “governments abiding by laws like everyone else” was rated, on average, 9.1 on a 10-point scale by respondents across the EU27. They also feel strongly that “courts should treat everyone equally,” which received an average 9 out of 10 points. Fundamental aspects of representative democracy like “free and fair elections” and “freedom of speech,” which both received a rating of 8.9, are also considered to be very important. Respondents also attach high importance to accepting election results, giving this item 8.6 out of 10 points in terms of its importance for democracy.

-

EU-wide, European citizens are, on average, somewhat more satisfied with how democracy works in the EU (60 percent) as compared to their own country (54 percent). There are major discrepancies across member states, however. Satisfaction with how democracy works in one’s own country is highest in the Netherlands (74 percent) and Germany (70 percent), and lowest in Spain (46 percent), Italy (40 percent) and Poland (35 percent).

-

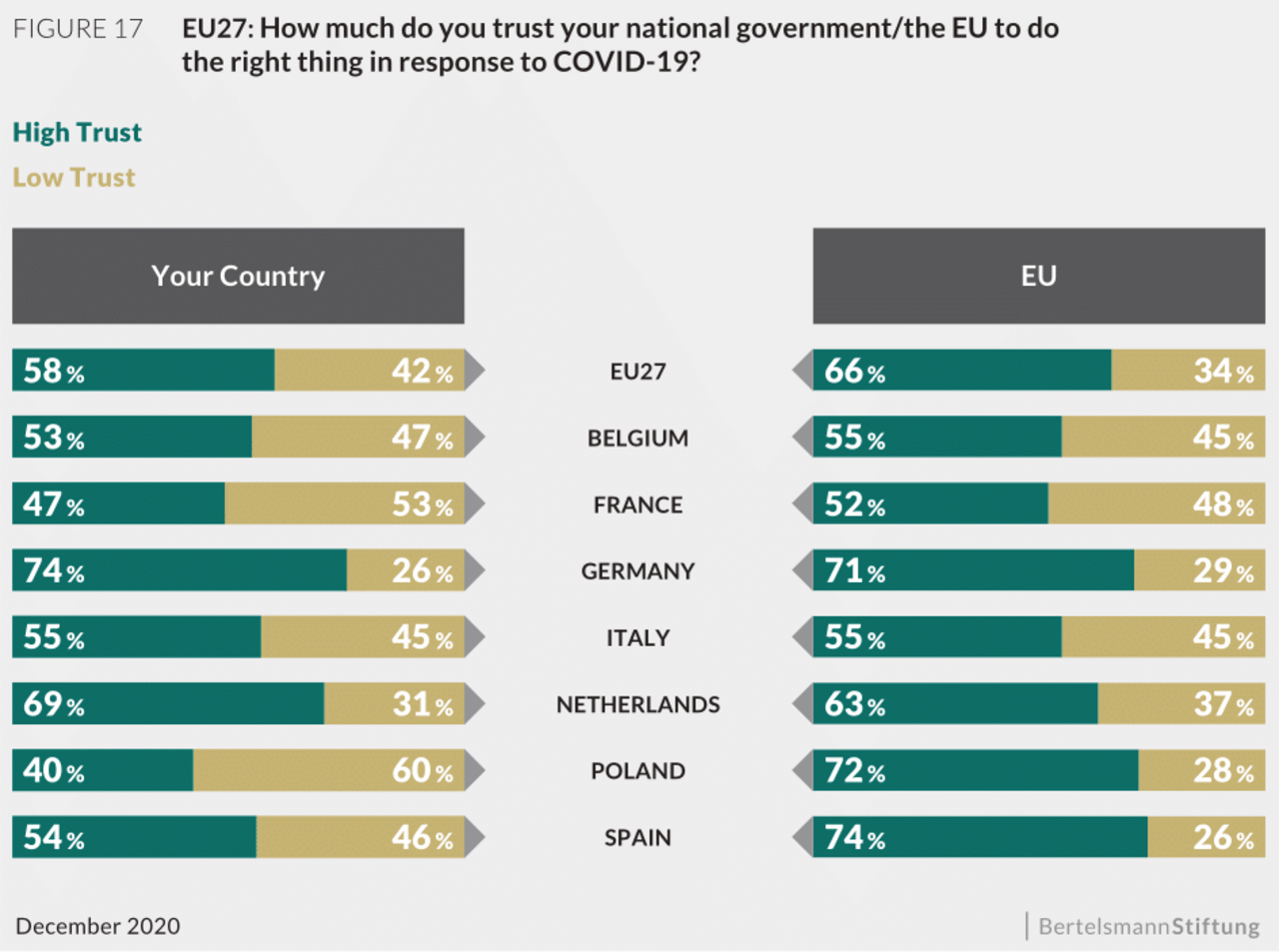

Most respondents in the EU27 state that they trust their government to do the right thing in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (58 percent), and an even larger share express trust in the EU in this regard (66 percent). As Figure 17 shows, there is nonetheless considerable variation on these points across member states. While a majority of Belgian, German, Italian and Spanish respondents trust their national government to manage the pandemic effectively, only a minority of French and Polish respondents feel the same about their government.

Introduction

For politicians across the globe, the COVID-19 pandemic is a stress test for governance. Curbing the coronavirus pandemic calls for swift and strong executive action. Indeed, many government leaders have resorted to extraordinary and sometimes draconian measures, which include placing restrictions on individual movement, introducing physical distancing requirements, and mandating businesses to close. And while lockdown measures clearly derive from public health needs, they also open up avenues for states to place further restrictions on fundamental democratic rights. Current measures run the risk of allowing leaders to engage in more lasting executive overreach and thus undermine key liberal democratic norms in society.

Concerns about pandemic-related democratic backsliding and the risk of weakening public support for appropriate measures underscore the importance of examining how European citizens view democracy and the rule of law. In this report, we examine not only how European citizens evaluate the state of democracy in their country and the EU more generally, but also what they think democracy ought to be.

Specifically, this report addresses three questions regarding EU citizens’ perceptions in this regard:

-

What are the most important constituent elements of democracy? Free and fair elections? Freedom of speech? Press freedoms? Judicial independence? Or govern- ments abiding by the law?

-

How well does democracy function in their own country and in the EU?

-

Finally, we close with a closer look at the pandemic situation in order to examine the third and final question: To what extent do European citizens trust their country’s government or the EU with regard to delivering an effective response to the COVID-19 pandemic?

This report seeks to answer these questions by presenting evidence based on a survey conducted in December 2020 in which we interviewed just under 12,000 EU citizens. In doing so, we present two sets of data. One set is based on a sample capturing public opinion across the EU27, while the other completes the picture with a more in-depth focus on respondents from the member states of Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland and Spain. Finally, we collate our data for these seven member states by party support to examine how partisan leanings might be associated with different views about democracy and how it is evaluated.

This report is organized into five parts. First, we briefly review the research on public support for democracy and introduce our methodology for measuring views on democracy and evaluations of how well it works. Second, we examine what European citizens believe are the most important constituent elements of democracy and how these perceptions differ across EU member states and partyaffiliation. Third, we explore how European citizens evaluate the way democracy works in their country and the EU, and how these evaluations differ across EU member states and party affiliation. Fourth, we investigate the extent to which European citizens trust that their government and the EU can respond effectively to the pandemic and how this differs across EU member states and party affili- ation. Finally, we close by reflecting on the possible lessons for political leaders in defending democracy, the rule of law and democratic practices in the context of a pandemic or similar crisis.

Public support for democracy

Citizens’ support for their country’s political system is a classical theme within political science. In his pioneering study of political support as the set of shared views and evaluations held by a population regarding its political system, David Easton (1965, 1975) distinguished between specific and diffuse support. The aspect of diffuse support refers to evaluations of the regime, broadly defined as the system of government and the constitutional arrangements underlying it. Specific support relates more to everyday policy, that is, the binding collective decisions and ac- tions taken by political actors operating in the broader system of government (see also Norris 1999). Whereas specific support constitutes a running mental tally that fluctuates with government performance, diffuse support derives from a loyalty to the underlying principles and institutions of a political system (Citrin et al. 1975).

Diffuse support, because it refers to the constituent principles and institutions of a political order, is seen to be essential to this order. While specific support may fluctuate as political systems falter in responding to external shocks or natural disasters, the political system nonetheless survives because people maintain a deeper loyalty to its essential principles and institutions. Diffuse support thus functions like a “reservoir of goodwill” toward the system, even when its per- formance doesn’t always prove satisfactory for everyone (Easton 1965: 125).

At the core of citizen support for representative democracy is their commit- ment to its essential democratic principles and institutions. The political theorist Robert Dahl (1998) suggests that representative democracy depends not only on its substance but also on its procedures. In terms of substance, political repre- sentatives must ensure that their actions deliver citizens the public goods and services they prefer—at least some of the time. However, majority rule makes it unlikely that each individual will receive their preferred goods and services most of the time. If individuals fail to obtain those goods and services they value most, broader faith in effective institutions that provide a fair articulation of different interests should nonetheless result in popular (or diffuse) support for the system overall. This broader faith in the system should also ensure losers’ consent, that is, support for the rules of the game among those who support the opposition (Anderson and Guillory 1997). Democracy needs to rely on a specific set of procedures that are widely accepted and perceived to be fair if the system as a whole is to endure. The stability of democracy is undermined when a significant share of the public questions democratic procedures.

While the concept of diffuse support has been very influential in the literature, it has not proved easy to conceptualize empirically (Inglehart 2003; Rose et al. 1999).

First, it is difficult to determine which items should be used to capture diffuse political support. Different countries have different ways of codifying democraticprocedures, as constitutional arrangements differ. Second, there might be a difference between how a person thinks about democracy as an ideal, and the way in which they evaluate how democracy works in practice. Third, to what extent is there a consensus regarding the essential democratic procedures within a specific representative democracy? In order to deal with this complexity and make it easier to capture political support for democracy in empirical terms, Mónica Ferrín and Hanspeter Kriesi (2016) distinguish between people’s views about democracy and their evaluations of democracy. While views about democra- cy refer to normative ideals of democracy (i. e., ideas “about what democracy should be”), evaluations of democracy refer to assessments of how democracy has been implemented in one’s country (i. e., evaluations of how “democracy works”) (Ferrín and Kriesi 2016: 10). Both components are important when measuring empirically citizens’ support for democracy.

In this report, we capture people’s views about democracy by asking respondents to rate, on a scale from 1 (not important) to 10 (very important), the importance of certain items for democracy. Our survey included a list of eleven items that are often considered to be constituent elements of a democracy.

- Government abides by the law, like everyone else

- Courts keep the government from acting beyond its authority

- Courts treat everyone equally

- Minority groups’ rights are protected

- Freedom of speech

- Media is free to criticize government

- Opposition is free to criticize government

- Political parties offer distinct alternatives

- Strong leadership

- The Peaceful acceptance of election results

- Free and fair elections

In a next step we captured people’s evaluations of democracy by asking respondents how satisfied they are with the way democracy works in their country, and in the EU. Respondents could choose one of the following answers: 1. Very sat- isfied, 2. Somewhat satisfied, 3. Somewhat not satisfied, 4. Not at all satisfied. We recoded these answers, categorizing responses 1 and 2 as “satisfied”, and responses 3 and 4 as “dissatisfied”.

Finally, we sought to capture respondents’ trust in their own government as well as the EU by posing the following question: “How much do you trust your national government/ EU to do the right thing in response to the COVID-19 virus health emergency?” Respondents could again choose among four responses: 1. Completely, 2. Somewhat, 3. Not really, 4. Not at all. We recoded these answers, categorizing responses 1 and 2 as having trust in the COVID-19 response, and responses 3 and 4 as distrusting the COVID-19 response.

Europeans’ views regarding democracy

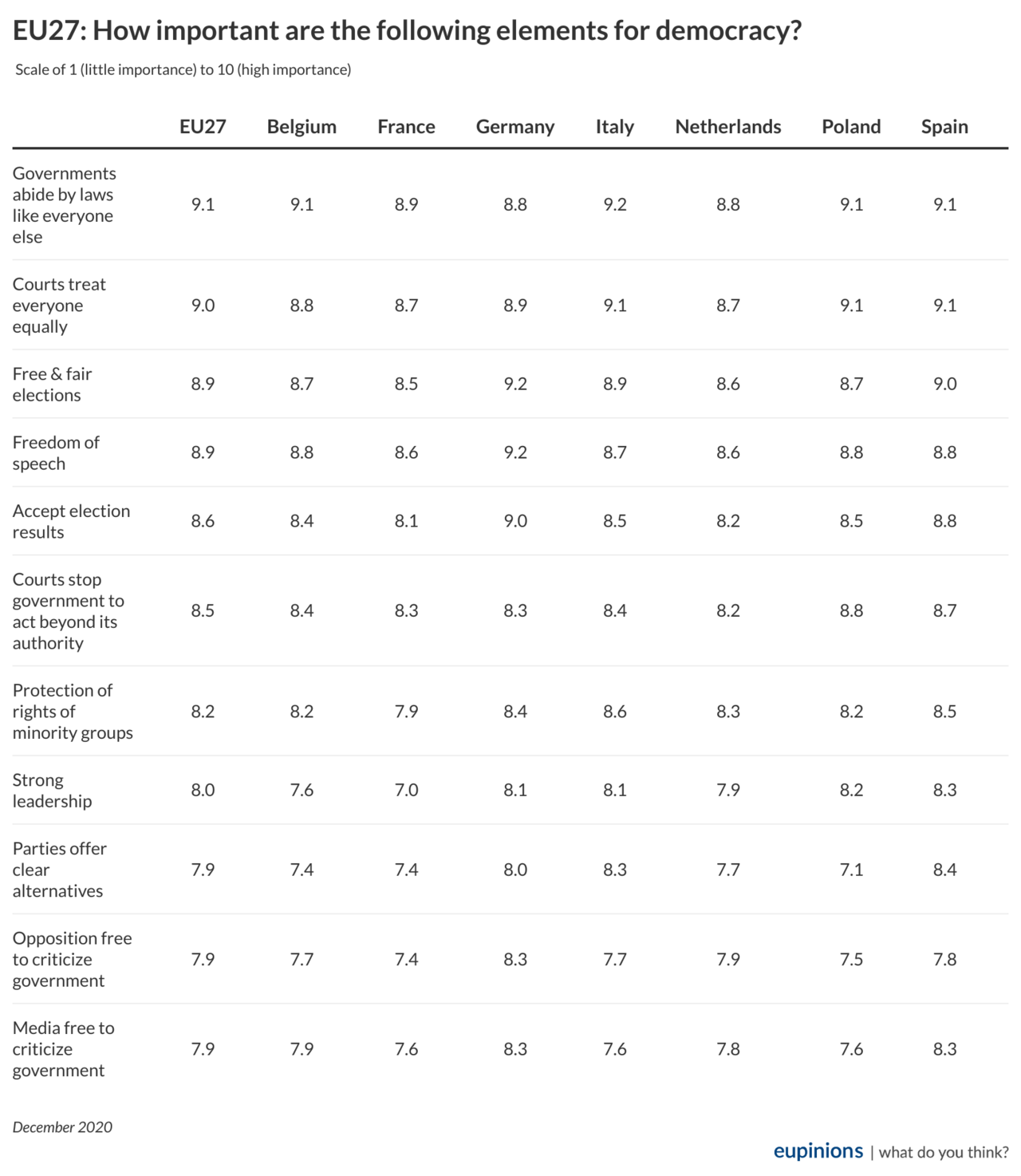

Let us first explore what European citizens think democracy should entail. Figure 1 shows the importance European citizens in the EU27 and several individual member states attach to certain things when they think about democracy. Recall that respondents were asked to rate, on a scale of 1 (not important) to 10 (very important), the importance of each item listed in Figure 1. Overall, respondents within the EU27 think that all of the listed items are important for democracy, as all items received a rating of 7.9 or higher, on average. Interestingly, with an average rating of 8, having a “strong leadership” was also considered to be important.

Figure 1

Figure 1 also shows that respondents within the EU27 attach great importance to rule-of-law issues when it comes to democracy. Indeed, they gave both “governments abide by laws like everyone else” and “courts should treat everyone equally” high ratings on the scale (9.1 and 9, respectively).

Fundamental aspects of representative democracy like “free and fair elections” and “freedom of speech” are rated as very important (8.9). The need to peacefully accept election results also ranks highly in the minds of respondents across the EU27 (8.6).

The results for the seven member states we subjected to a more in-depth study reveal compelling differences. For example, compared to other member states, the presence of strong leadership is viewed as less important by French respondents (7). Spanish respondents (8.3) attach the greatest importance to the presence of strong leadership, though this is closely followed by Polish respondents (8.2) and German and Italian respondents (8.1).

While for Germans “free and fair elections” are most important to democracy, respondents in the other member states attribute the greatest importance to “governments abide by laws like everyone else”, which is followed by the “courts should treat everyone equally”. This suggests that the rule of law is perceived as crucially important by many, including Polish respondents. Political parties’ ability to offer distinct alternatives as well as the media and opposition’s freedom to criticize the government are viewed as slightly less important by Polish, Belgian and French respondents.

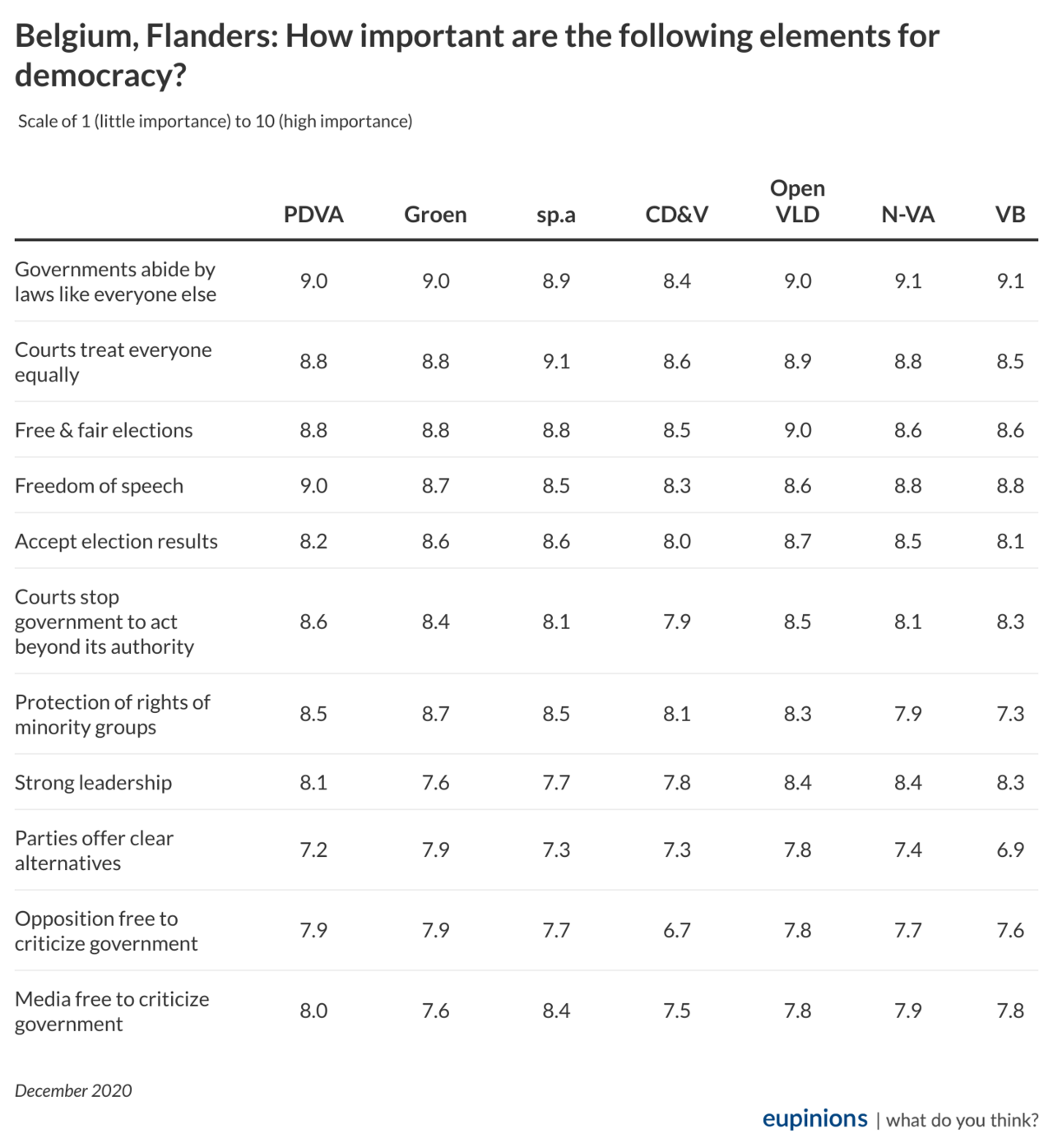

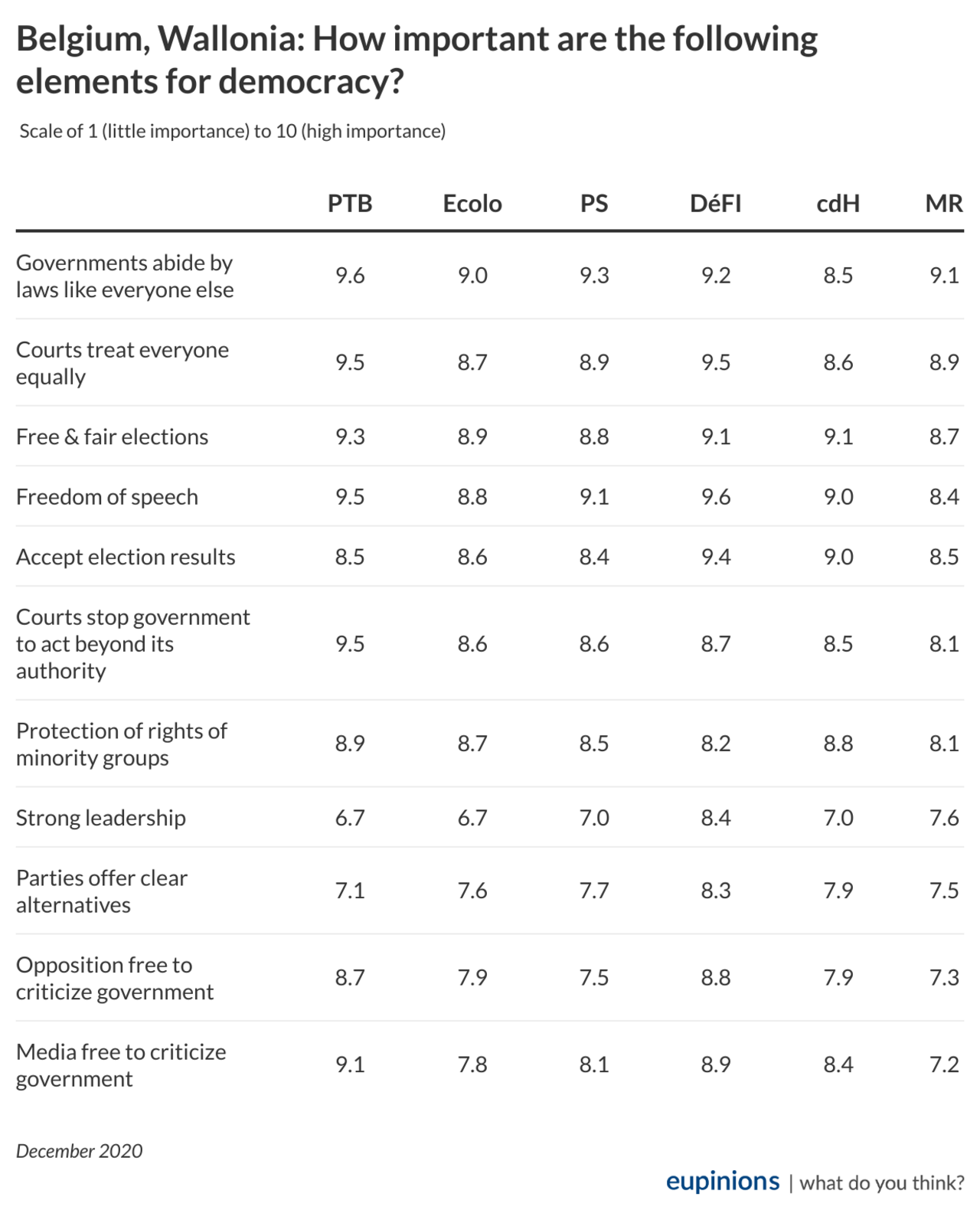

In a next step, we take a closer look at the seven states selected for in-depth analysis to see if and how views of democracy differ by political party affiliation. Figures 2.1 and 2.2 show the data for Belgian respondents split by region (i.e., Flanders and Wallonia). Flemish respondents, regardless of their partisan leanings, attach considerable importance to both “governments abide by laws like everyone else” and “courts should treat everyone equally.” Having “strong leadership” is most important among those who support the populist right-wing parties Vlaams Belang and the Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie. “Parties offering clear alternatives” is the least important among Vlaams Belang supporters (6.9), and most important among Groen supporters (7.9). Considering the recent developments around the acceptance of the US Presidential election outcome, it may be worth noting that supporters of the Vlaams Belang party attach quite high importance to the peaceful acceptance of election outcomes in a democracy.

Figure 2.1

Figure 2.2

Respondents from Wallonia, regardless of party support, consider rule-of-law items – particularly “governments abide by laws like everyone else” – important. Supporters of the Centre Démocrate Humaniste rate “free and fair elections” as most important (9.1), while supporters of the Démocrate Fédéraliste Indépendant say this about “freedom of speech” (9.6). Overall, Wallonia respondents, excepting Démocrate Fédéraliste Indépendant supporters, attach less importance to having “strong leadership” than do most of their Flemish counterparts.

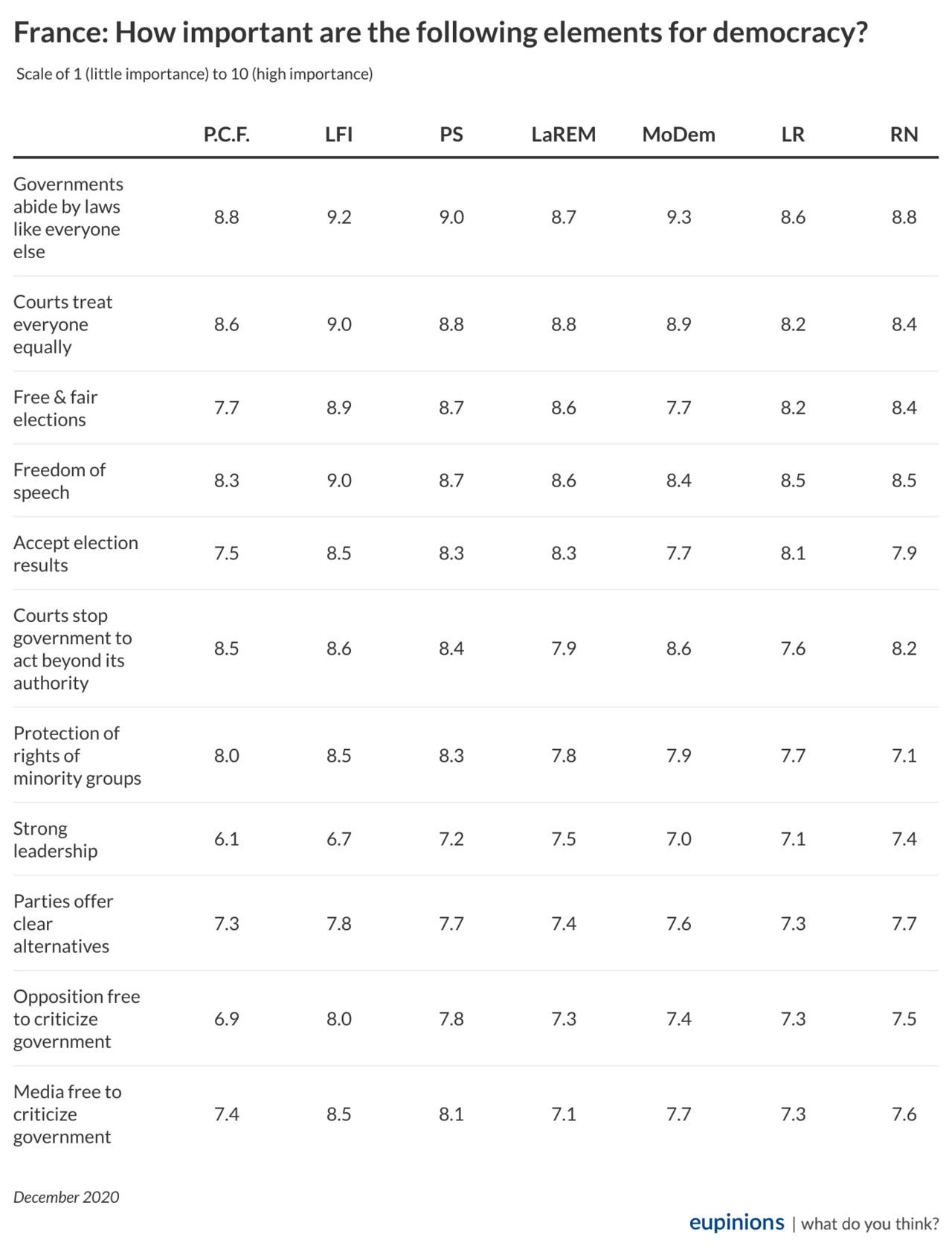

Figure 3 shows how French respondents view democracy. As is the case for Flemish and Walloon respondents, the French consider rule-of-law related items to be very important for democracy. For them, “governments abide by laws like everyone else” and “courts should treat everyone equally” are the most important elements of democracy. Notably, supporters of the populist right-wing Rassemblent National rate the importance of accepting election outcomes (7.9) somewhat higher than do their counterparts who support the Parti Communiste (7.5). Moreover, Parti Communiste supporters are least likely to think that having a “strong leadership” is important for democracy (6.1). This item is most important for supporters of La Republique En March (7.5). Overall, compared with respondents in other member states, French respondents find it less important to have “strong leadership”.

Figure 3

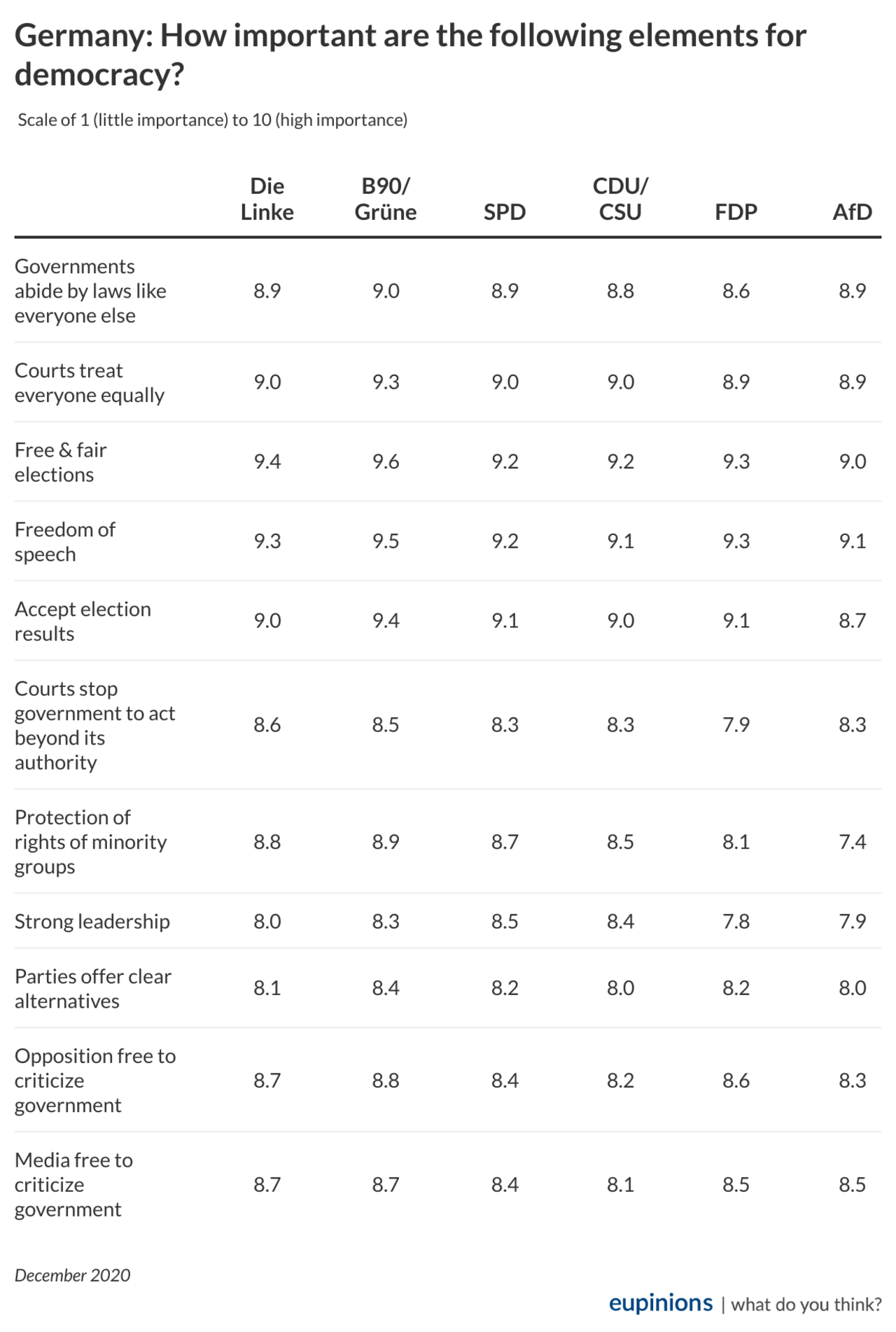

The views regarding democracy among German respondents are displayed in Figure 4. German respondents generally consider “free and fair elections” and “freedom of speech” to be most relevant for democracy. Having a “strong leadership” is ranked quite highly among supporters of the Christlich Demokratische Union and Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (8.4 and 8.5, respectively). Consistent with rankings among supporters of populist right-wing parties in Flanders and France, Alternative für Deutschland supporters in Germany also consider it very important to “accept election outcomes” (8.7).

Figure 4

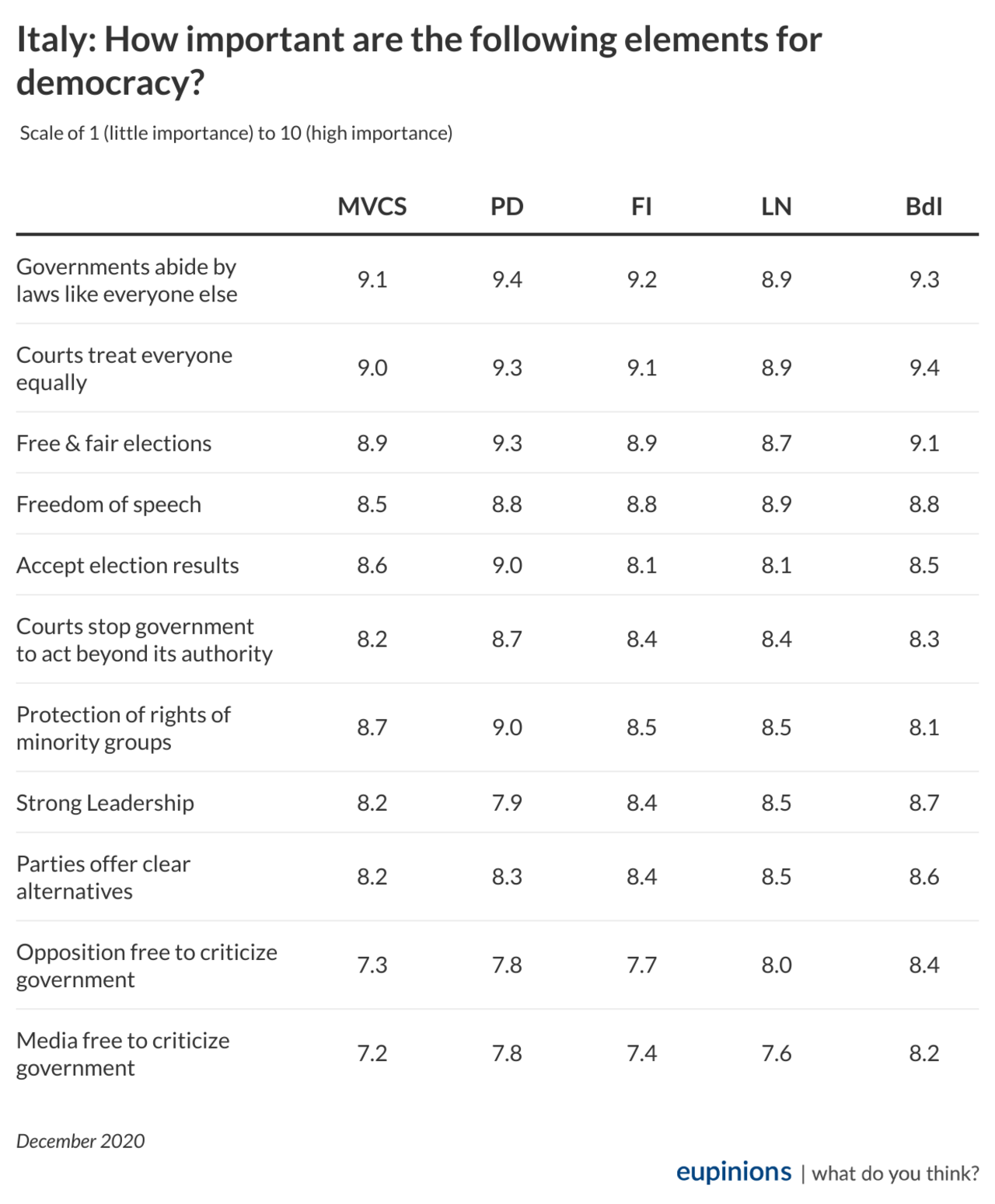

Figure 5 provides an overview of what Italian respondents think are the most important elements of democracy. As in France, respondents in Italy attach considerable importance to the rule of law when thinking about what democracy should entail. The items “governments abide by laws like everyone else” and “courts treat everyone equally” are perceived to be very important. These items are followed closely by “free and fair elections”, which is also rated highly by supporters of the populist right-wing Lega and Fratelli d’Italia parties. Interestingly, although supporters of these parties attach significant importance to having a strong leadership (8.5 and 8.7, respectively), they also consider it important to accept the outcome of an election (8.1 and 8.5, respectively).

Figure 5

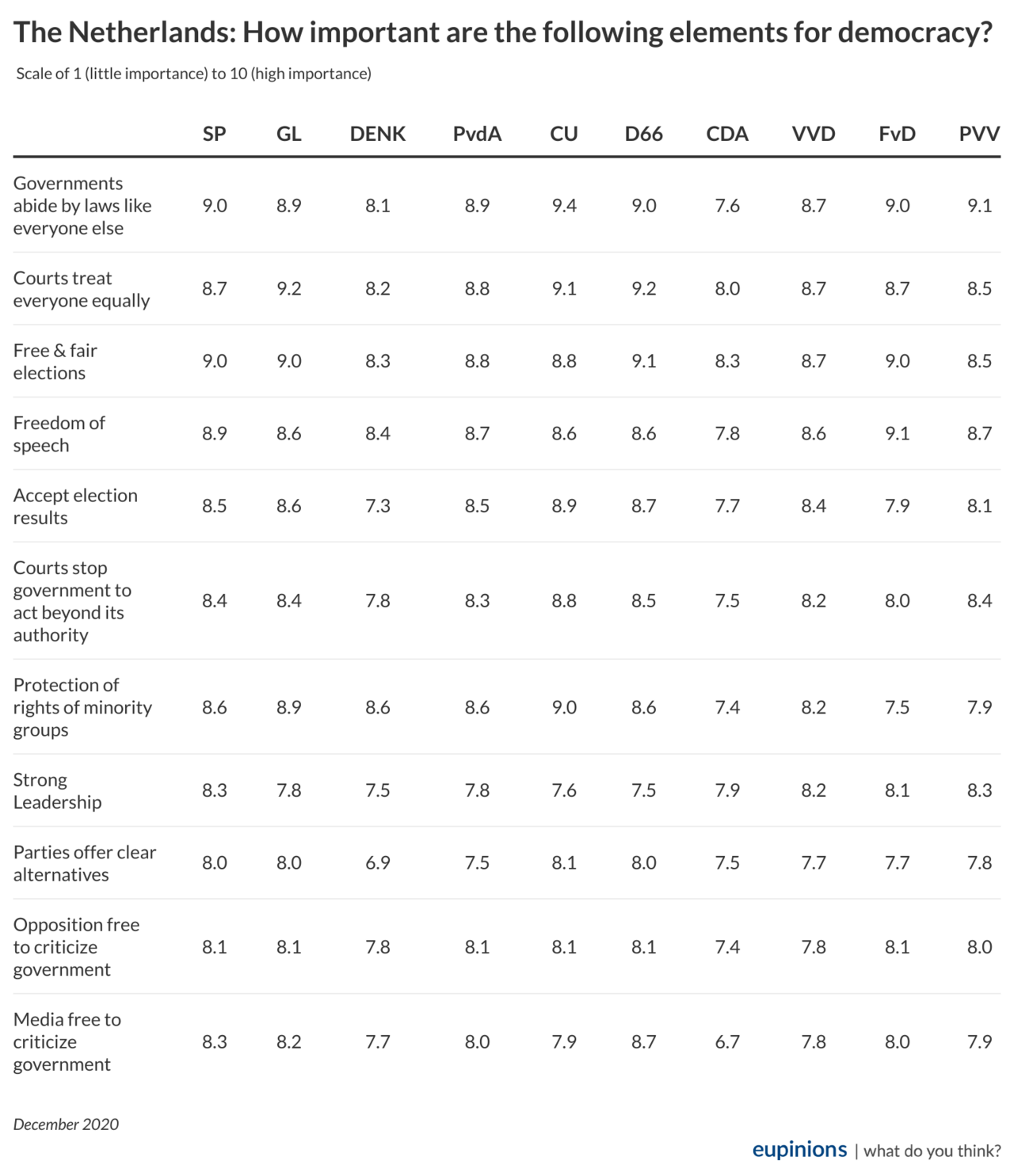

Figure 6 shows the views of Dutch respondents. Here, as in other member states, the rule-of-law items, “governments abide by laws like everyone else” and “courts treat everyone equally” are identified as very important by all respondents. In addition, however, the Dutch also consider “free and fair elections” to be very important. Like their counterparts in Flanders, Germany, France and Italy, Dutch supporters of the populist right-wing Partij van de Vrijheid and Forum voor Democratie parties consider it important for democracy to accept the outcome of an election (8.3 and 8.1, respectively). For Forum voor Democratie supporters, “freedom of speech” is viewed as the most important element of democracy (9.1).

Figure 6

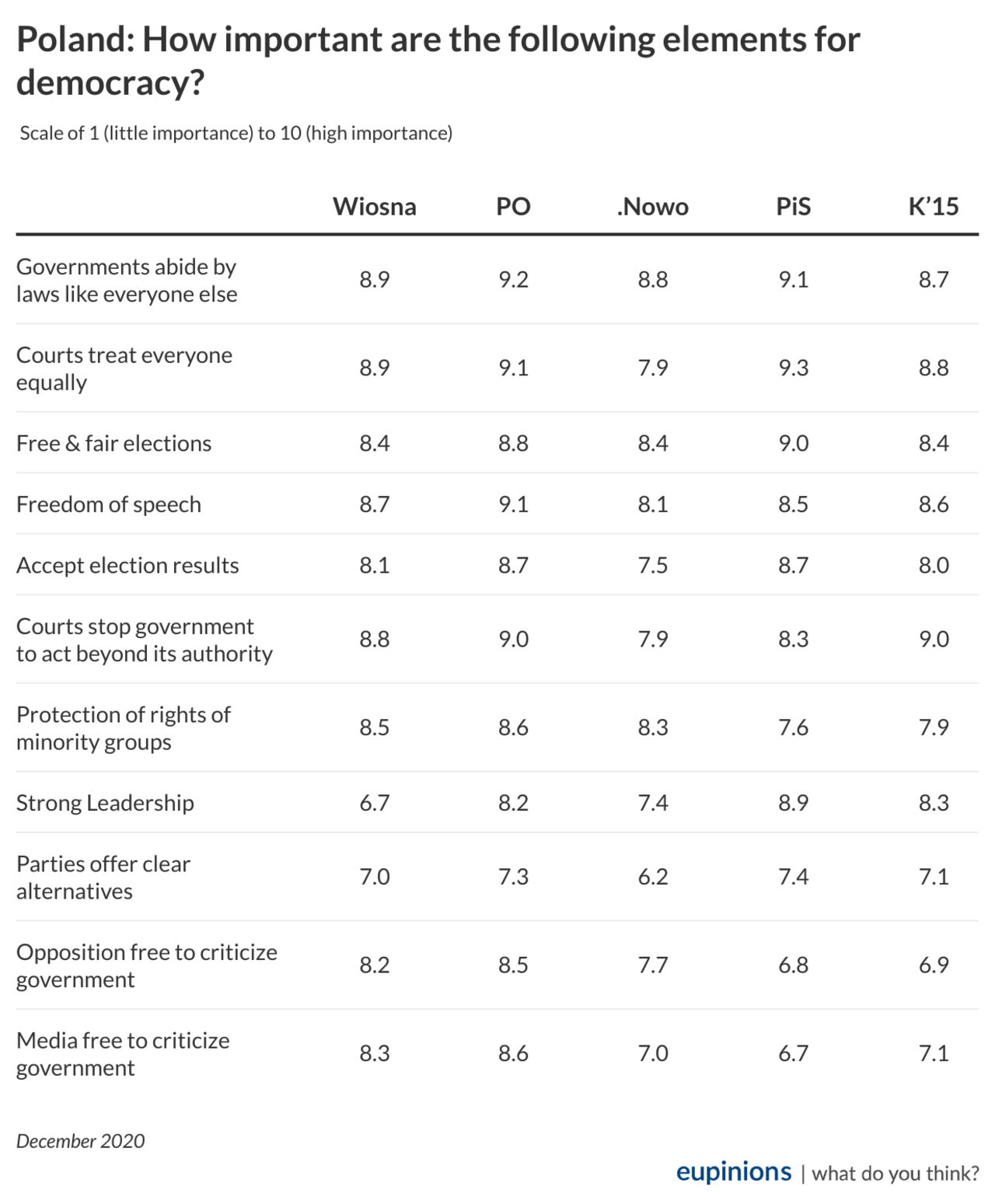

The views of Polish respondents are shown in Figure 7. Again, supporters of almost all parties attach very high importance to the rule of law items “governments abide by laws like everyone else”, “courts treat everyone equally” and “courts stop government to act beyond its authority”. Support for a “strong leadership” is very high (8.9) among those who support the ruling party Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, which contrasts significantly with the response among those in support of the opposition party Wiosna (6.7). Accepting an election outcome finds strong support across the spectrum of Polish respondents.

Figure 7

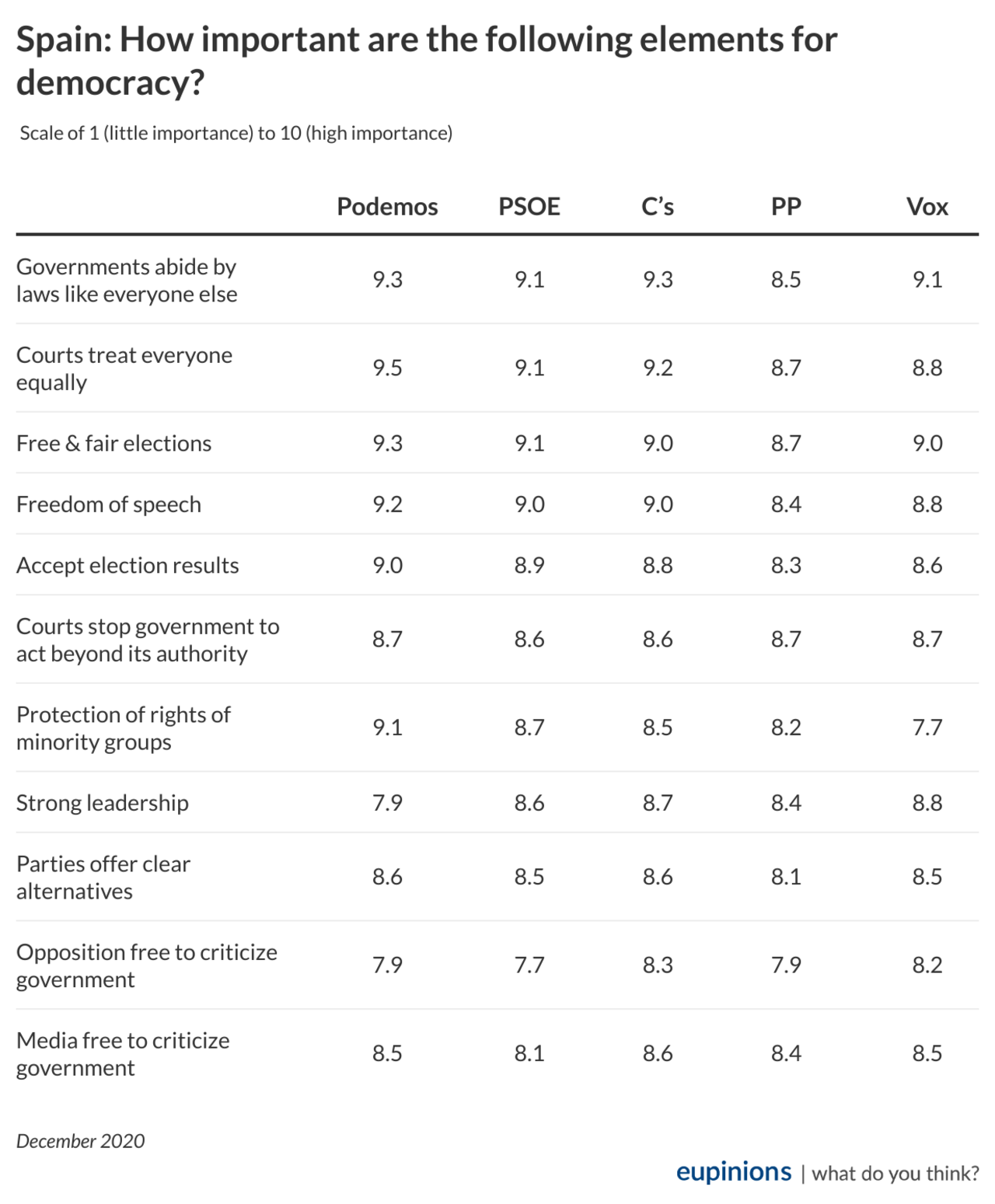

Figure 8 provides an overview of Spanish respondents’ views regarding the substance of democracy. As is the case of Poland, respondents in Spain rate as very important the rule-of-law items “governments abide by laws like everyone else,” “courts treat everyone equally,” and “courts stop government to act beyond its authority,” which are followed by “free and fair elections.” Having “strong leadership” is most important for supporters of the populist right-wing VOX party (8.8), but also for those who support the center-right Cuidadanos party (8.7). This is least important among supporters of the ruling left-wing party, Podemos (7.9). As is the case in the other member states, respondents across the political spectrum, including VOX voters, think that accepting an election outcome is important (8.6).

Figure 8

Europeans’ evaluations of democracy

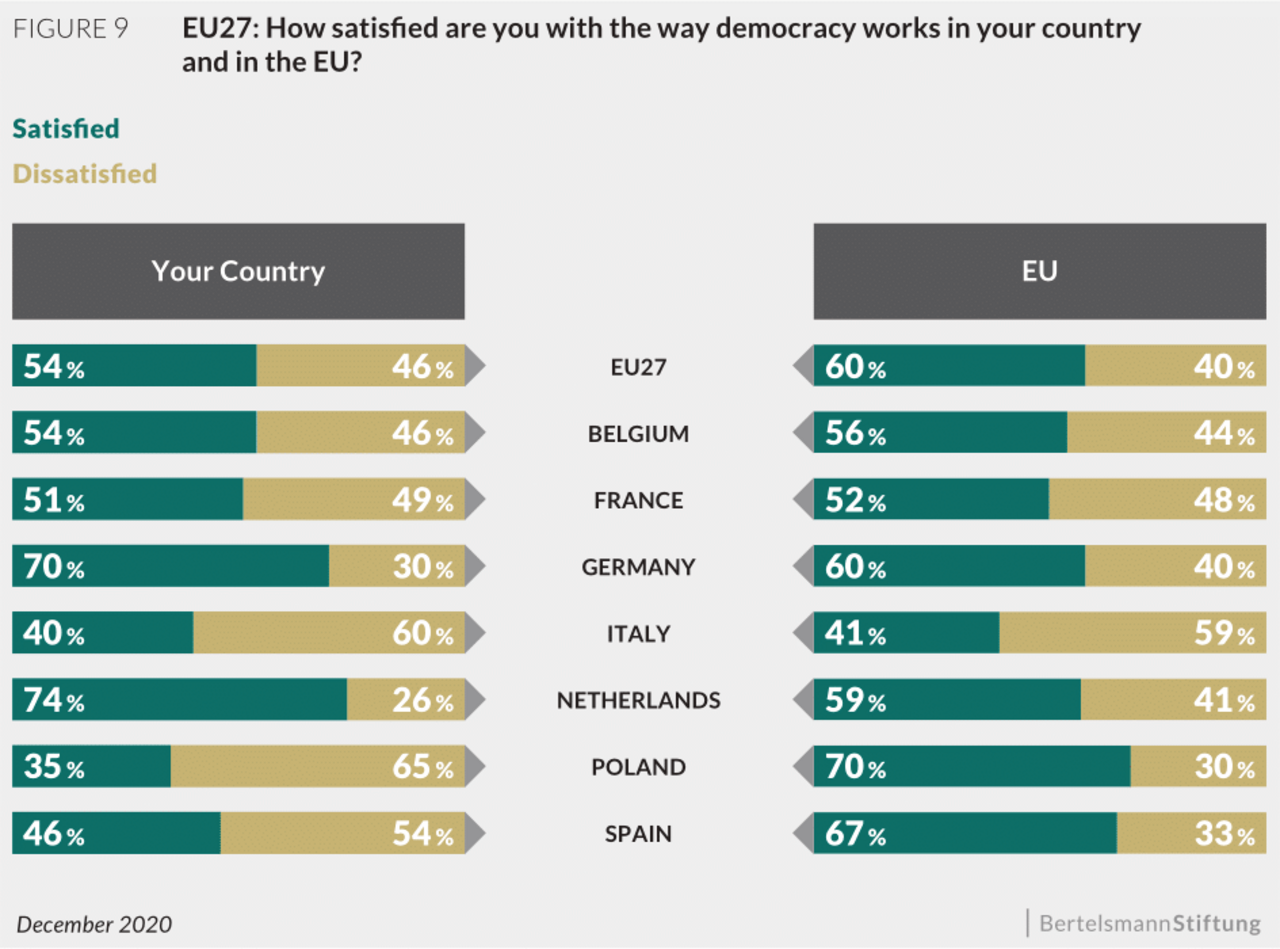

After having explored what European citizens think characterizes a good democracy, in a second step, we examine how they evaluate the ways in which democracy works in their own country and in the EU. Figure 9 below shows the degrees of satisfaction and dissatisfaction in the EU27, as well as the seven individual member states. Figure 9 shows that European citizens are, on average, slightly more satisfied with the way democracy works in the EU than they are with how it works in their own country. Some 60% of EU27 respondents express satisfaction with the way democracy works in the EU, while 54% express the same about their own country. Figure 9 also suggests that numbers vary significantly across member states. Satisfaction with the way democracy works in one’s own country is the highest in the Netherlands (74%) and Germany (70%). These figures stand in stark contrast to those in Poland (35%), Italy (40%) and Spain (46%). Interestingly, Polish and Spanish respondents are much more satisfied with the way democracy works in the EU (70% and 67%, respectively). Italian respondents are the least satisfied with how democracy works in the EU, with only 41% expressing satisfaction – which is also on par with their satisfaction levels for democracy at home. Respondents in Belgium and France are split more evenly when it comes to satisfaction with the way democracy works in their respective countries and in the EU, though both are slightly more positive about democracy in the EU.

Figure 9

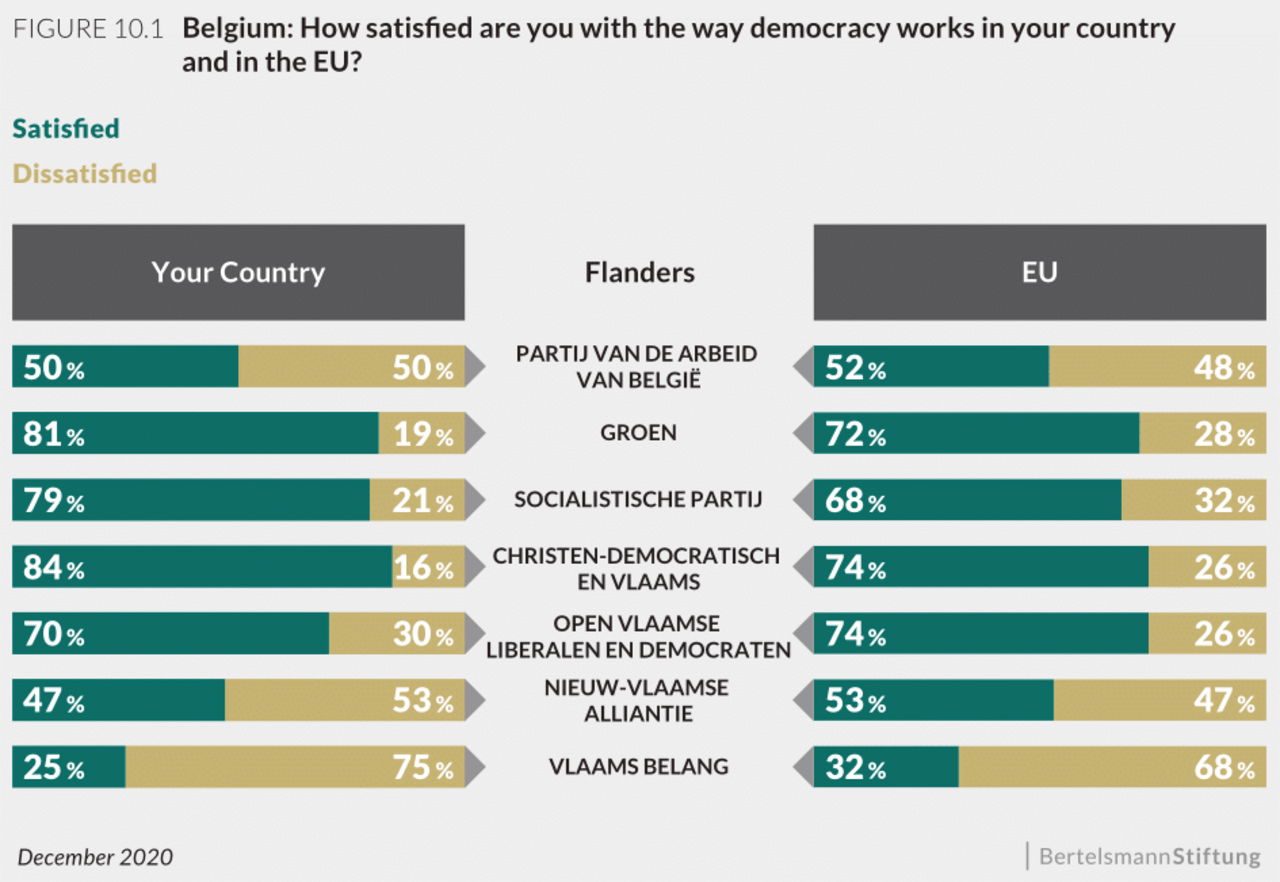

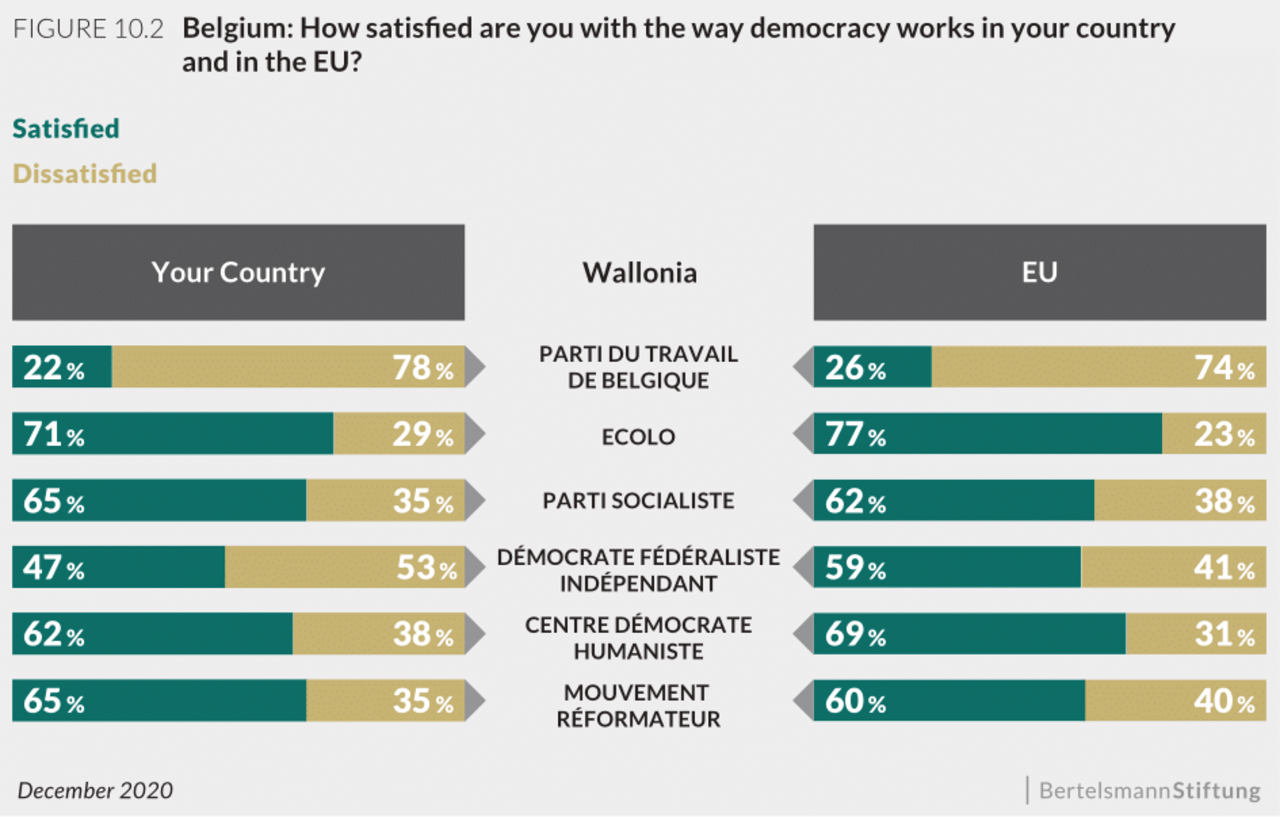

Figures 10.1 and 10.2 show satisfaction levels with the way democracy works at the national and EU levels among Flemish and Walloon respondents. Supporters of the populist right-wing Vlaams Belang party are least satisfied with the way democracy works in Belgium and the EU. Only 25% of Vlaams Belang supporters state that they are satisfied with the way democracy works in Belgium, and 32% say they are satisfied with the way democracy works in the EU. Supporters of the Christen-Democratisch en Vlaams party are most satisfied with democracy at both the national and EU levels (84% and 74%, respectively). When it comes to respondents in Wallonia, supporters of the Parti du Travail de Belgique party express the lowest levels of satisfaction: 22% are satisfied with how democracy works in Belgium, and 26% are satisfied with how democracy works in the EU. Supporters of the Ecolo party are most satisfied with the way democracy works at home (71%) and in the EU (77%).

Figure 10.1 (Flanders)

Figure 10.2 (Wallonia)

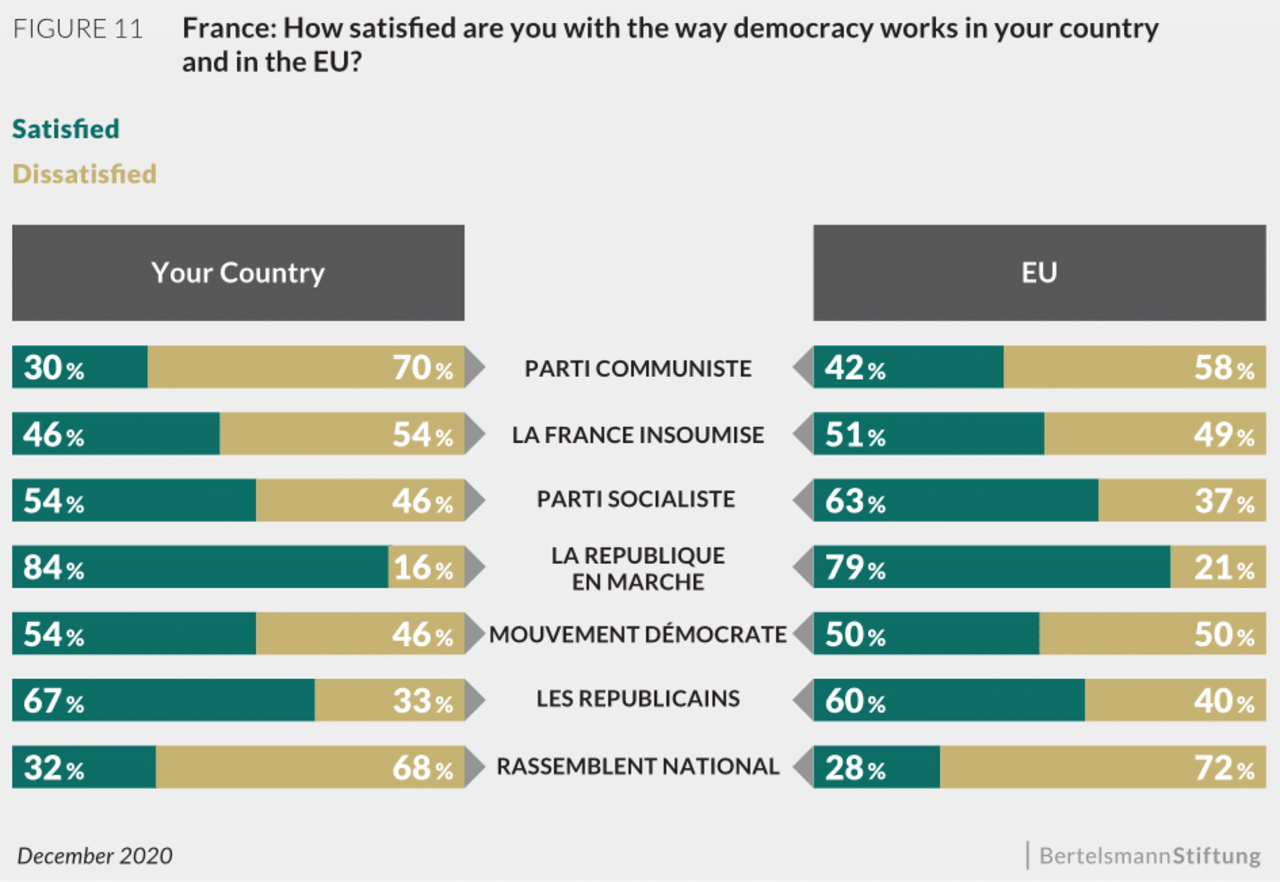

The evaluations of French respondents are displayed in Figure 11. Supporters of the far left-wing Parti Communiste party and the populist right-wing Rassemblent National are least satisfied with the way democracy works in France (30% and 32%, respectively) and in the EU (42% and 28%, respectively). Supporters of the ruling Le Republique en Marche party are most satisfied, with 84% expressing satisfaction with democracy at home and 79% with democracy in the EU.

Figure 11

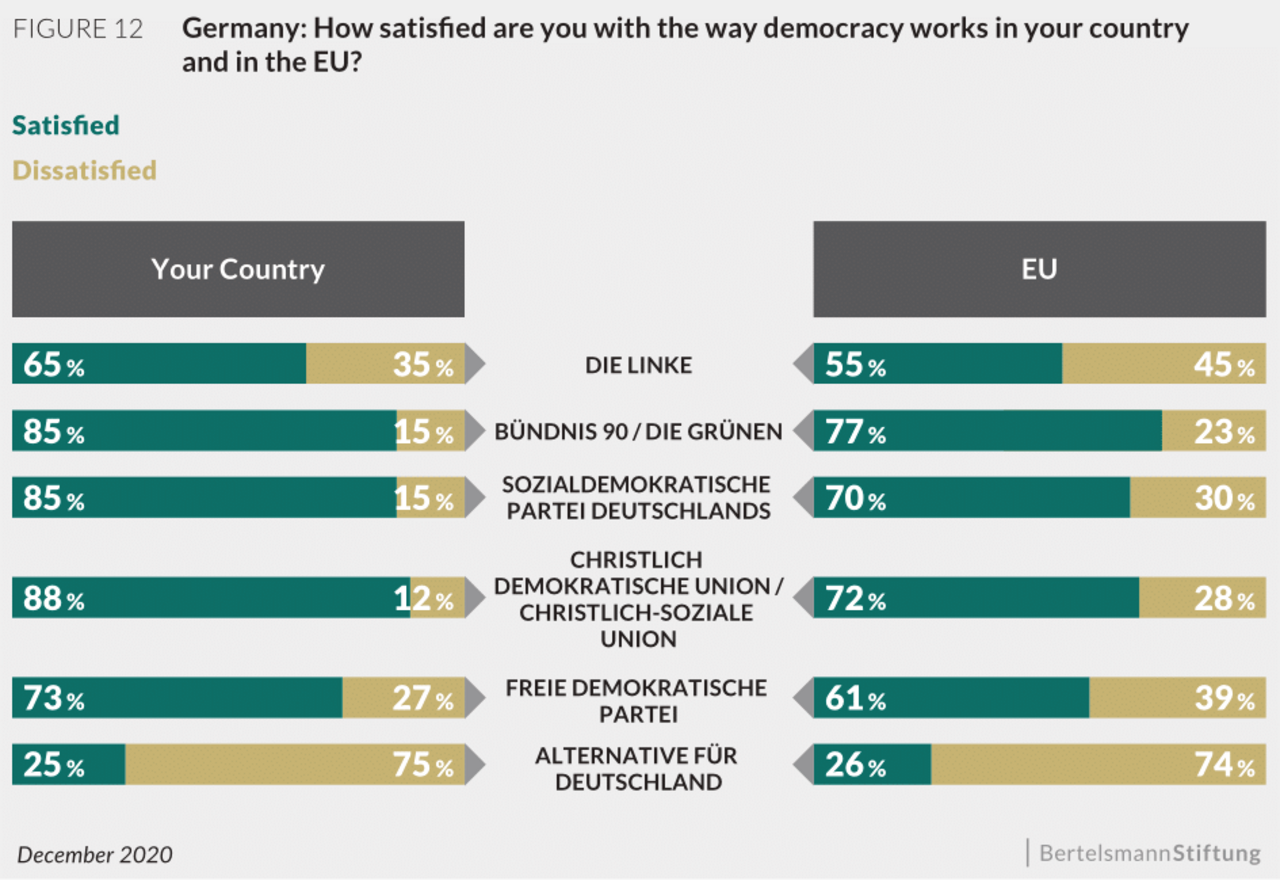

Figure 12 shows the percentage of German respondents expressing satisfaction with democracy in Germany and in the EU. The most satisfied are supporters of the Christlich Demokratische Union party. Some 88% of them state that they are satisfied with the way in which democracy works in Germany, and 72% are satisfied with the way it works in the EU. Supporters of the populist right-wing Alternative für Deutschland party are least satisfied. Only 25% of these respondents express satisfaction with the way democracy works in Germany, and only 26% express satisfaction with how it works in the EU.

Figure 12

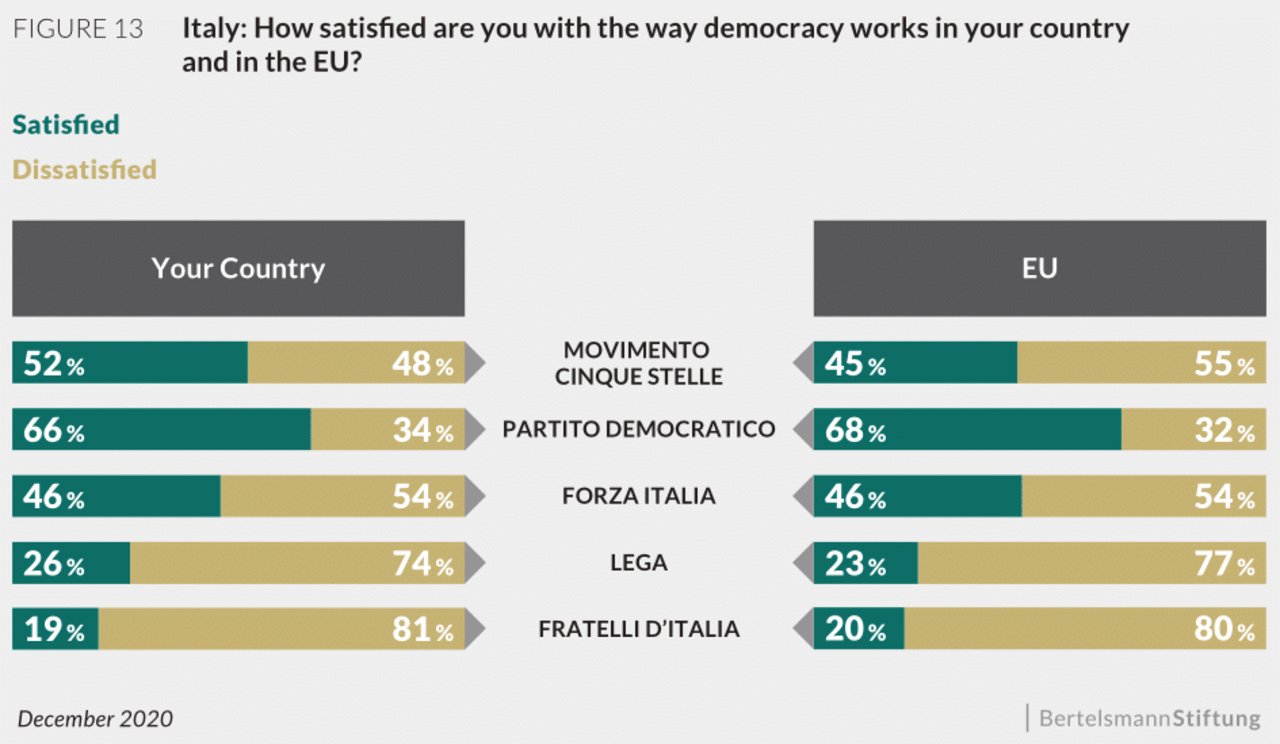

Figure 13 depicts Italian respondents’ evaluations of how democracy works in Italy and in the EU. Supporters of the populist right-wing Fratelli d’Italia party are least satisfied with how democracy works at home (19%) and in the EU (20%). Supporters of the center-left Partido Democratico party are most satisfied with how democracy works in Italy (66%) and in the EU (68%).

Figure 13

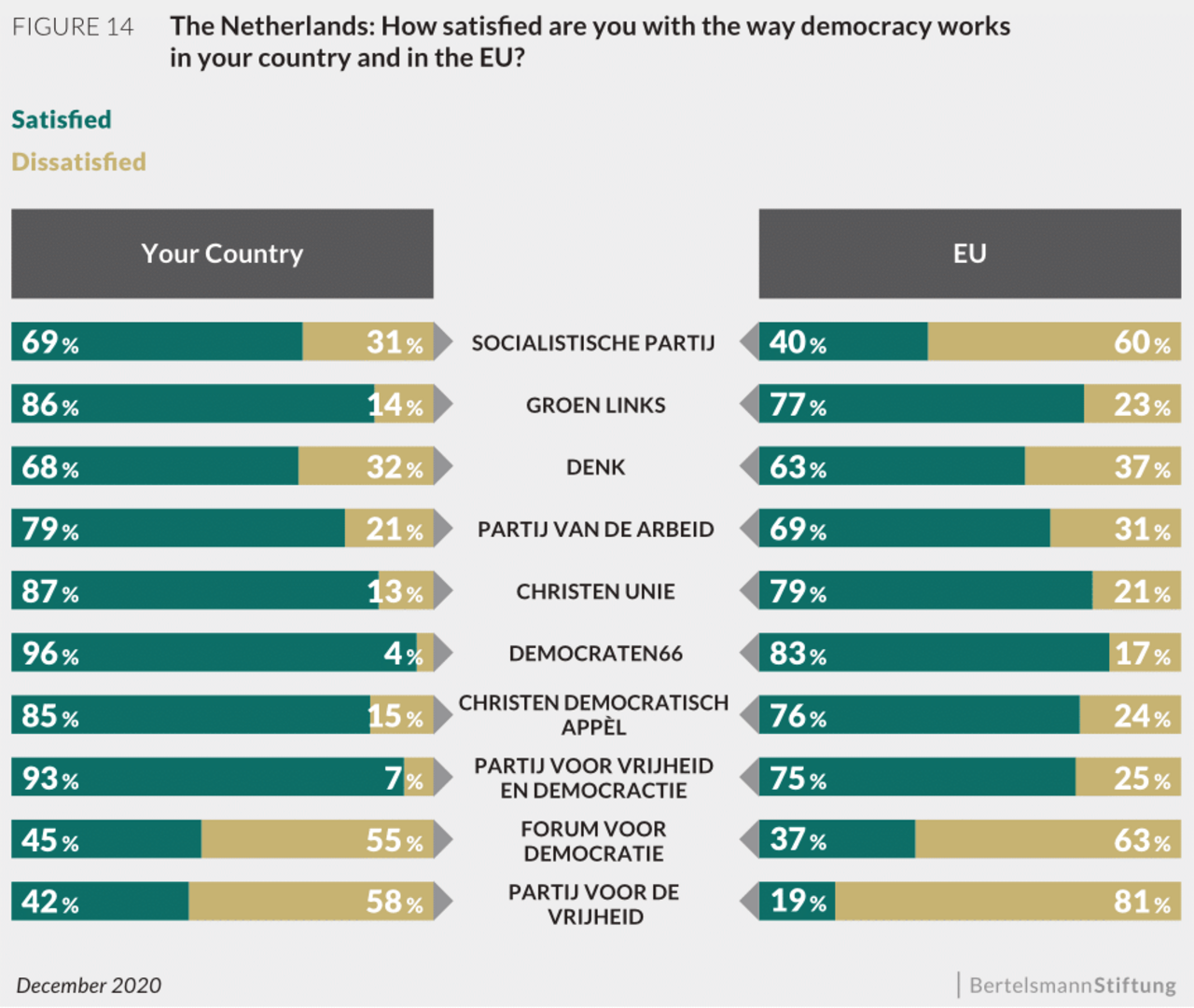

Figure 14 displays the ways in which different Dutch respondents evaluate how democracy works in the Netherlands and in the EU. As is the case in Belgium, France, Germany and the Netherlands, supporters of populist right-wing parties are least satisfied with the way in which democracy works – both in the Netherlands and in the EU. Only 42% of Partij van de Vrijheid supporters are satisfied with democracy in the Netherlands and only 19% are satisfied with democracy in the EU. Forum van Democratie supporters are somewhat more satisfied with democracy in the Netherlands (45%), and considerably more satisfied with democracy in the EU (37%). Supporters of the ruling party Partij voor Vrijheid en Democratie are most satisfied: 93% express satisfaction with democracy in the Netherlands, and 75% with democracy in the EU.

Figure 14

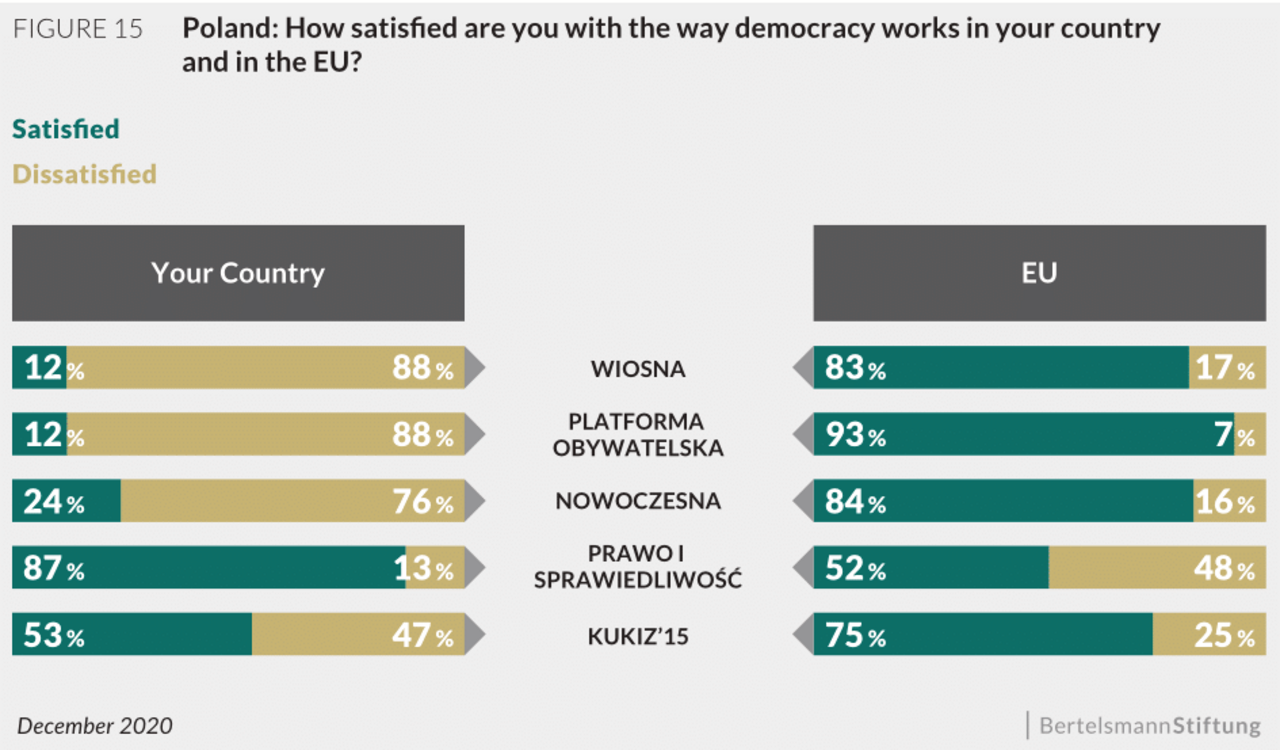

As Figure 15 shows, supporters of Poland’s ruling party, Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, are most satisfied with how democracy works in their country (87%), but less satisfied with how it works in the EU (52%). Supporters of the opposition party Wiosna are the least satisfied with how democracy works at home (12%), but they are very satisfied with how democracy works in the EU (83%).

Figure 15

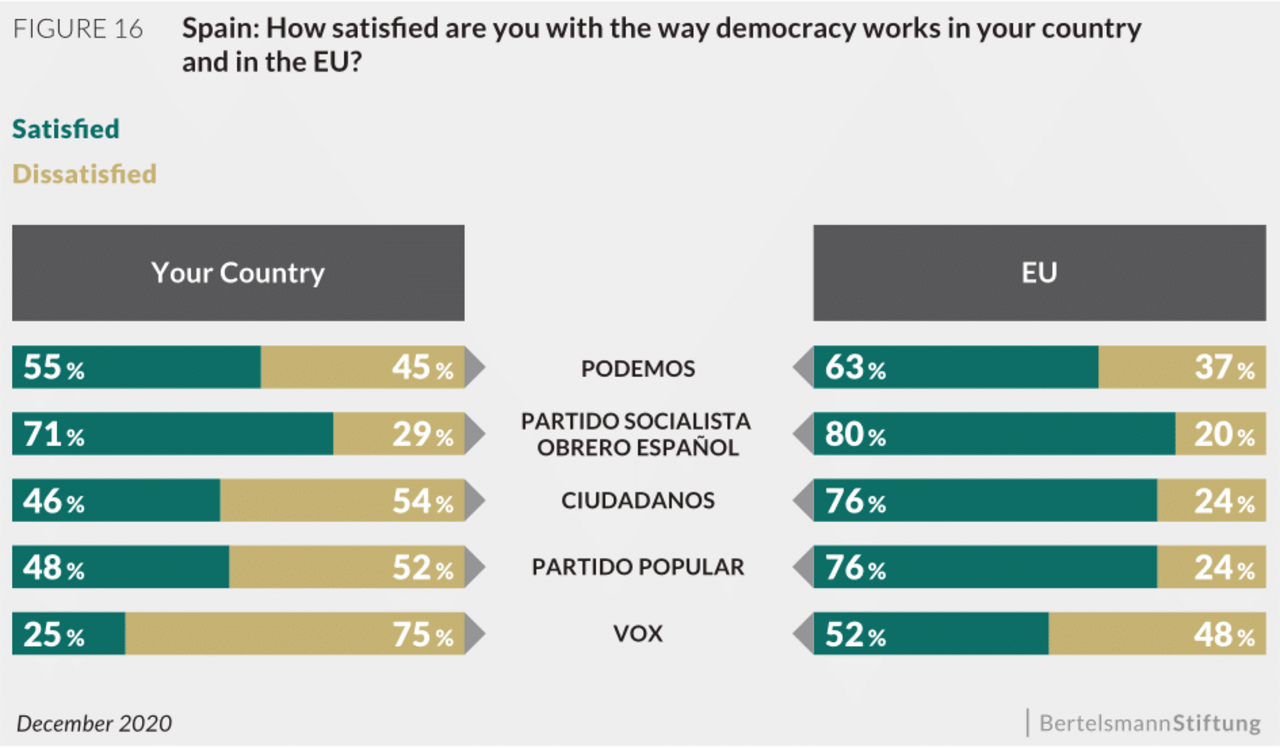

As Figure 16 shows, in Spain supporters of the populist right-wing VOX party are, similar to their counterparts in other member states, least satisfied with how democracy works at home (25%), but more satisfied with how it works in the EU (52%). Among Spanish respondents, supporters of the ruling party Partido Socialista Obrero Español are the most satisfied with how democracy works at home (71%), and they are even more satisfied with how it works at the EU level (80%).

Figure 16

Europeans’ trust in the pandemic response

In a final step, after having reviewed European citizens’ views and evaluations of democracy, we examine people’s trust in national government and the EU in the context of the pandemic. Figure 17 shows the share of respondents in the EU27 that trust their national government or the EU to respond effectively to the COVID-19 pandemic. A majority of EU27 respondents (58%) state that they trust their government to do the right thing in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and an even larger share (66%) trusts the EU in this regard. Figure 17 also displays considerable variation between member states. While a majority of Belgian, German, Italian and Spanish respondents trust their respective governments to deal effectively with the pandemic, this is true of only a minority of French (47%) and Polish (40%) respondents. Belgian, Dutch, German and Italian respondents express a similar level of trust in the EU as they do in their respective governments. French, Polish and Spanish respondents, however, are generally more trusting of the EU than of their own government in terms of responding to the pandemic.

Figure 17

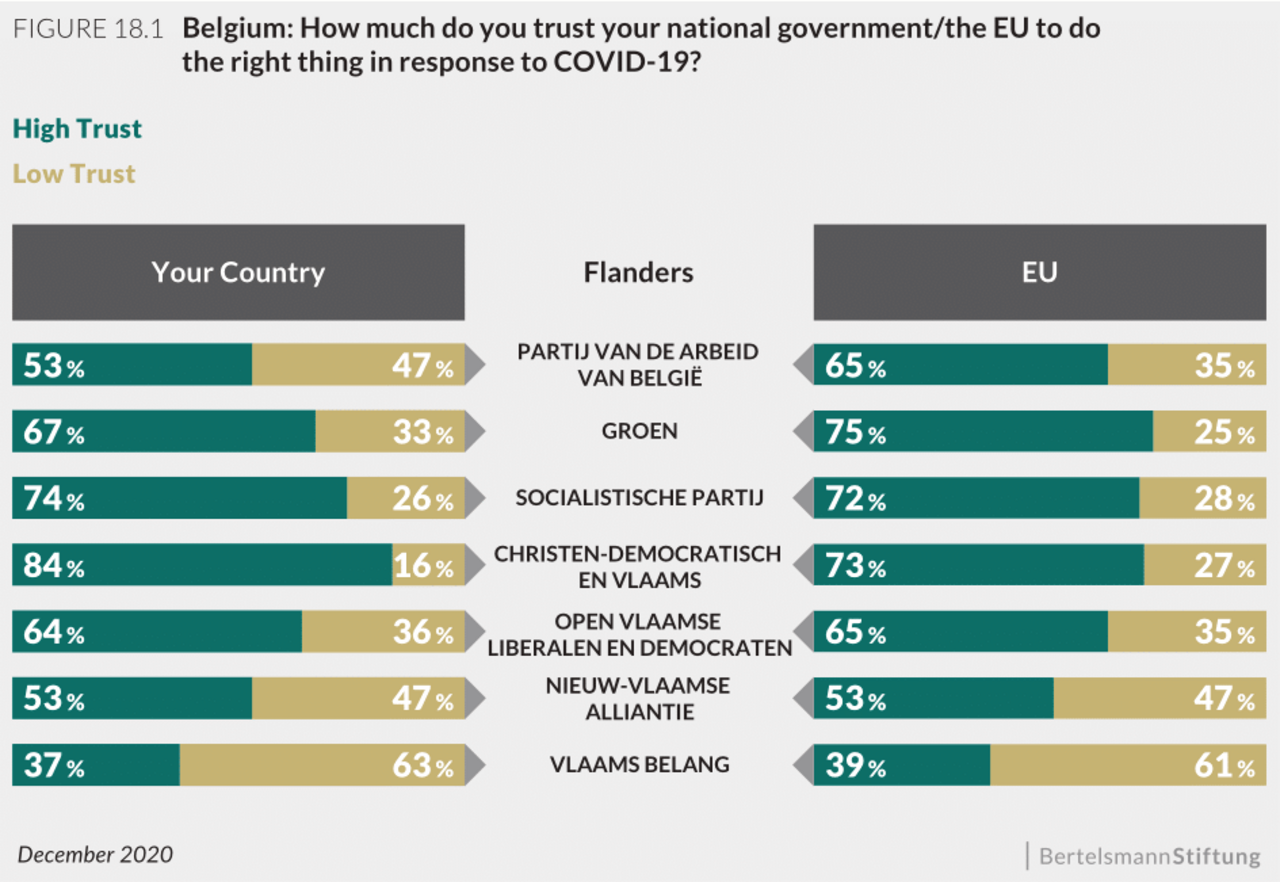

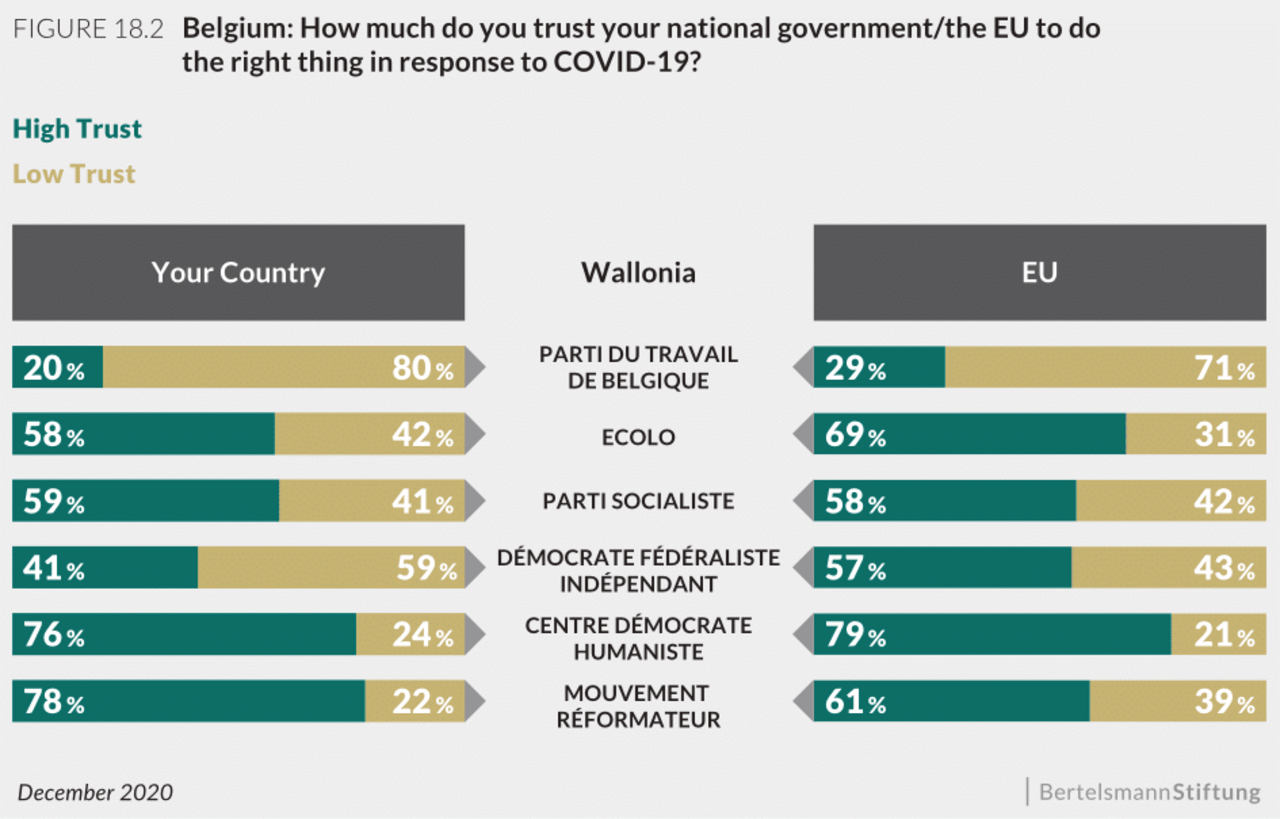

Figures 18.1 and 18.2 show the levels of trust in the Belgian government and the EU to effectively respond to the COVID-19 pandemic among respondents in Flanders and Wallonia. In Flanders, supporters of the populist right-wing Vlaams Belang party are the least trusting of the Belgian government (37%) and the EU (39%) with regard responding effectively to the pandemic. Those who support the Christen-Democratisch en Vlaams party express the most trust in the Belgian government (84%) and in the EU (73%) with respect to delivering an effective pandemic response. In Wallonia, supporters of the Parti du Travail de Belgique party are least trusting of the Belgian government (20%) and the EU (29%), while those in support of the Ecolo party are most trusting of their own government (58%) and the EU (69%).

Figure 18.1 (Flanders)

Figure 18.2 (Wallonia)

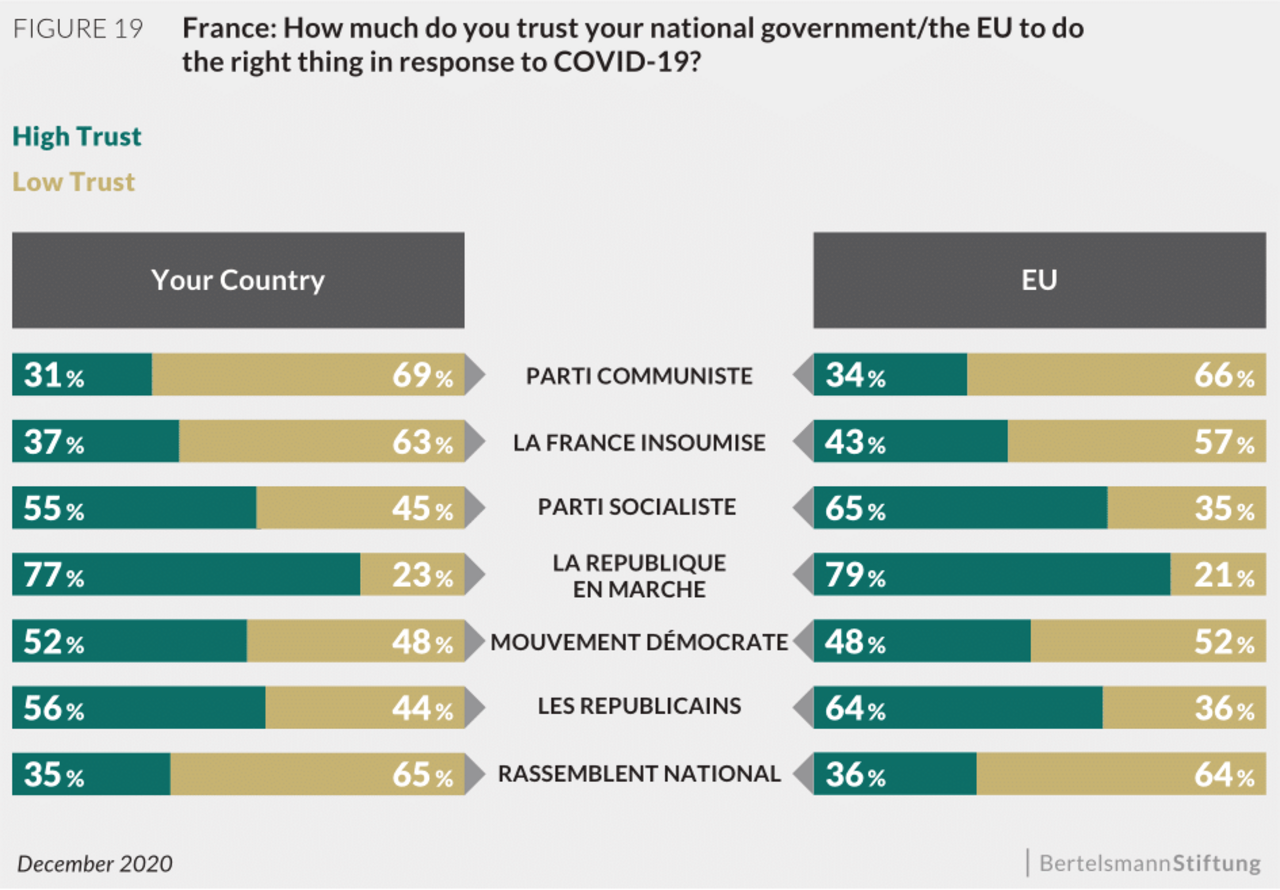

Figure 19 shows the share of French respondents who trust their national government and the EU to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic. As is the case in Flanders, supporters of the populist right-wing Rassemblent National party have little trust in their own government and the EU in this regard. Only 35% of Rassemblent National supporters trust the French government, and 36% trust the EU. Supporters of the ruling party, Le Republique en Marche, are most trusting of their own government (77%) and the EU (79%) in their capacity to deal with the pandemic.

Figure 19

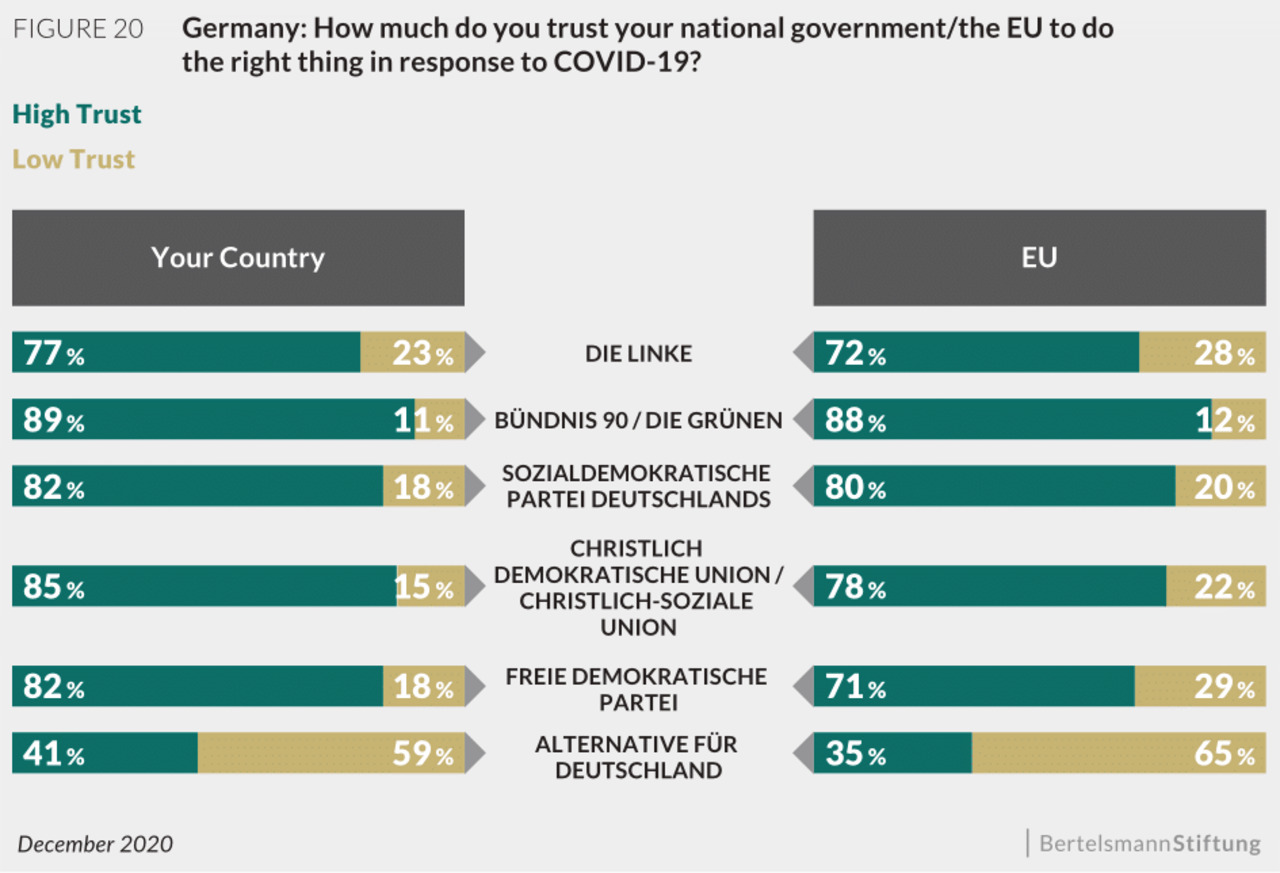

Figure 20 shows the percentage of German respondents stating that they trust their government and the EU to deliver an effective response to the pandemic. The most trusting are supporters of the Christlich Demokratische Union, with 85% expressing trust in the German government and 78% expressing trust in the EU to handle the situation well. Supporters of the populist right-wing Alternative für Deutschland are least trusting. Only 41% state that they trust the German government to respond effectively to the pandemic, and only 35% say the same of the EU.

Figure 20

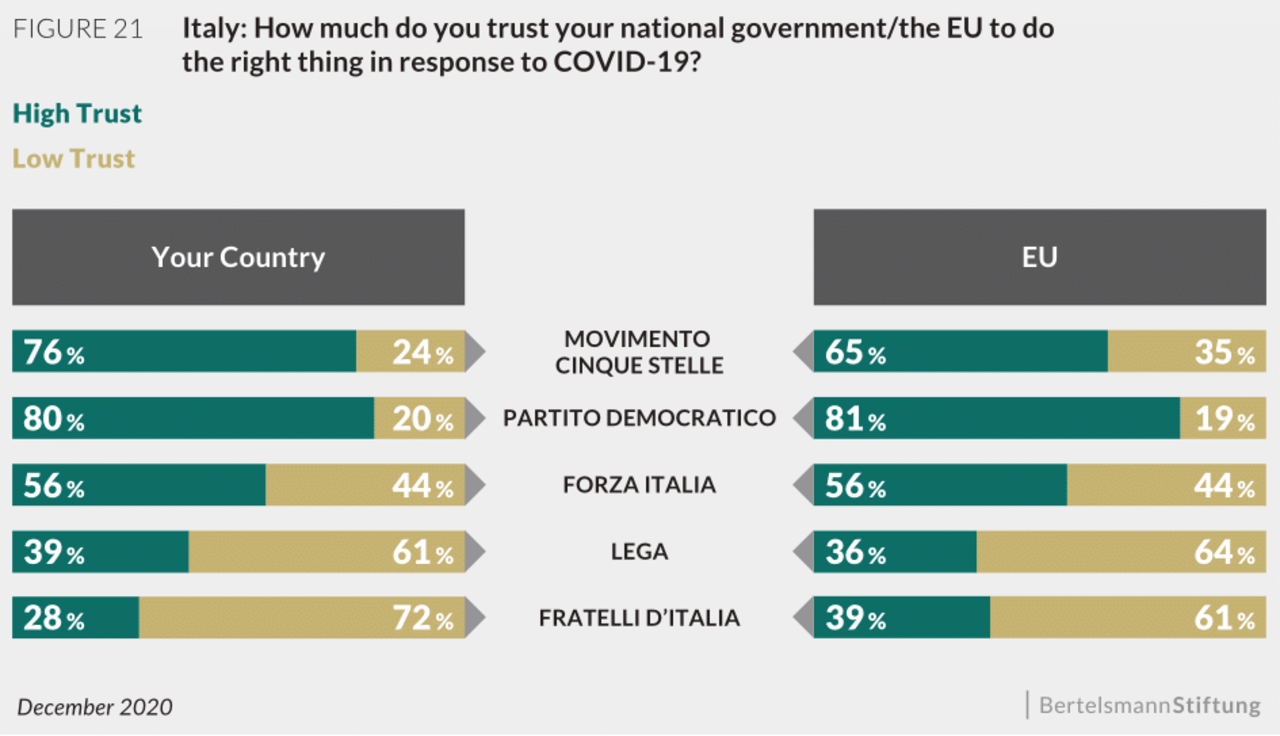

Figure 21 shows the extent to which Italian party supporters trust the Italian government and the EU to respond effectively to the pandemic. Those who support the populist right-wing Fratelli d’Italia party are least trusting of the Italian government (28%) and the EU (39%) in this regard. Supporters of the center-left Partido Democratico party are most trusting of their government (80%) and the EU (81%) in terms of delivering an effective pandemic response.

Figure 21

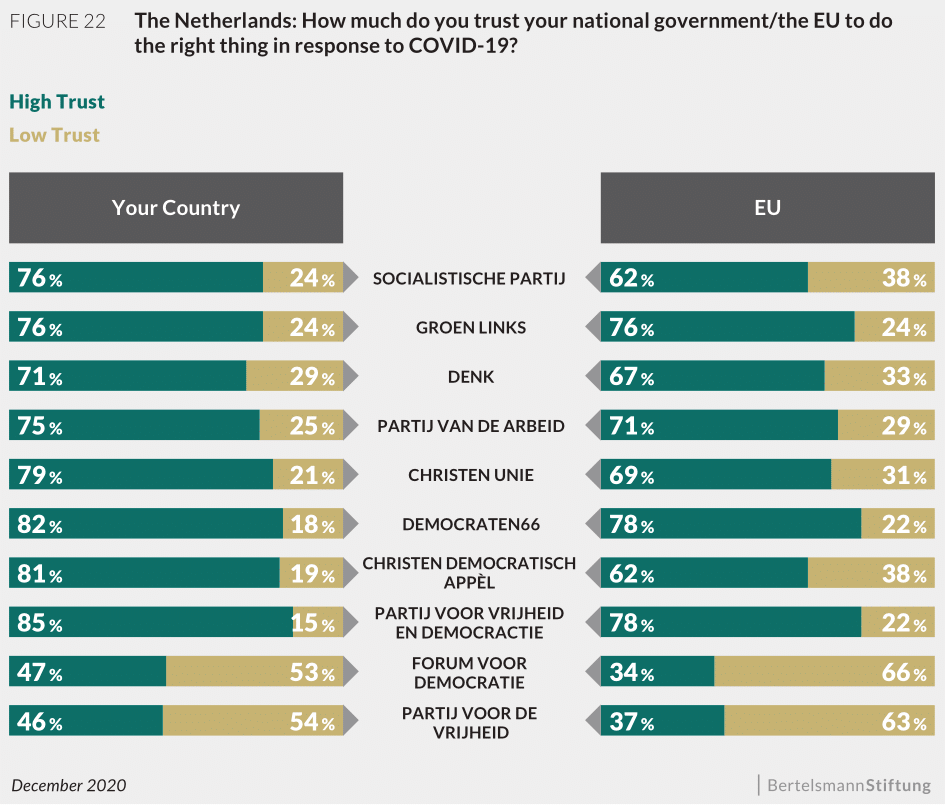

Figure 22 highlights differences in the extent to which Dutch respondents trust their own government and the EU in dealing with the pandemic. As is the case in Flanders, France, Germany and the Netherlands, supporters of populist right-wing parties are least trusting of the Dutch government and the EU when it comes to handling the pandemic. Some 46% of Partij van de Vrijheid supporters trust the Dutch government to do what’s necessary to curb the pandemic, while only 37% trust the EU to do the same. Whereas a total of 47% of Forum van Democratie supporters express trust in the Dutch government in this regard, only 34% of them trust the EU. Supporters of the ruling party, Partij voor Vrijheid en Democratie, are most trusting of their own government (85%) and the EU (78%).

Figure 22

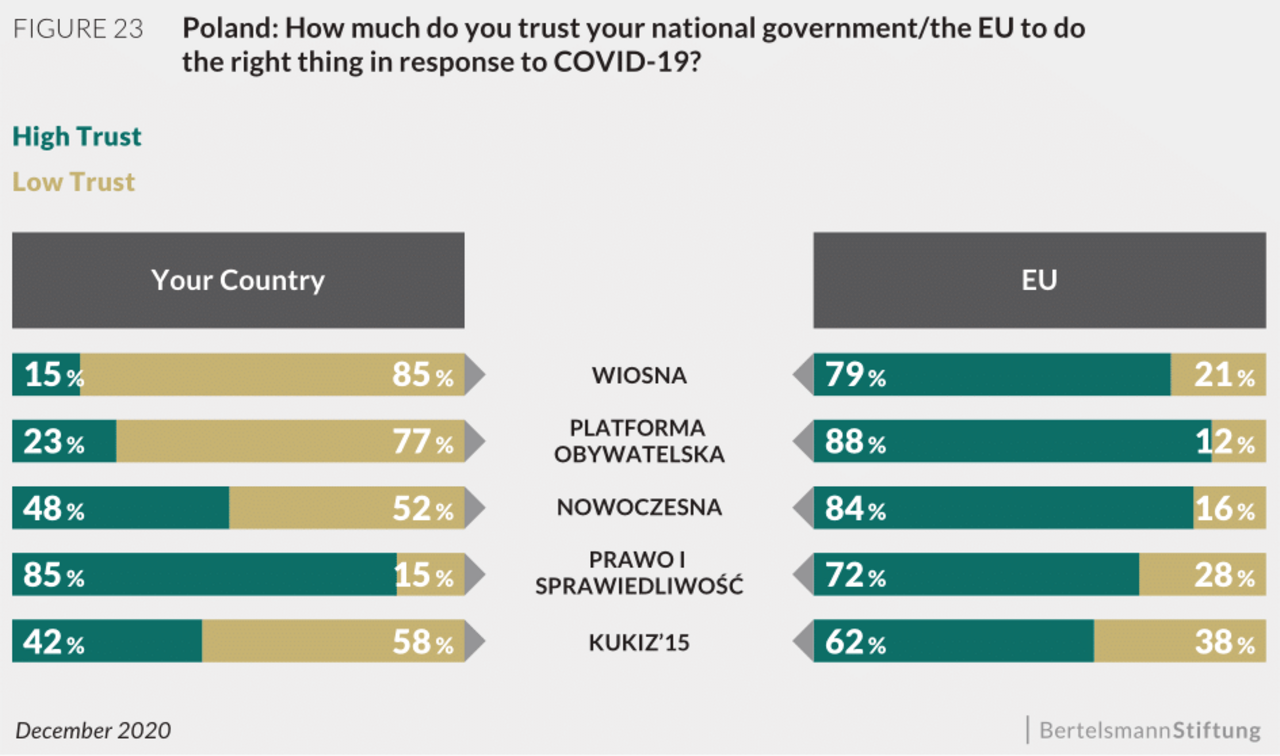

As Figure 23 shows, supporters of Poland’s ruling party, Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, are most trusting of their government’s ability to deal with the pandemic (85%). And while they express less trust in the EU’s ability to handle the pandemic, they are nonetheless relatively trusting (72%) of the EU. Supporters of the opposition party Wiosna express the least trust in the Polish government’s ability to respond effectively to the pandemic (15%), but they express considerable trust in the EU’s ability (79%).

Figure 23

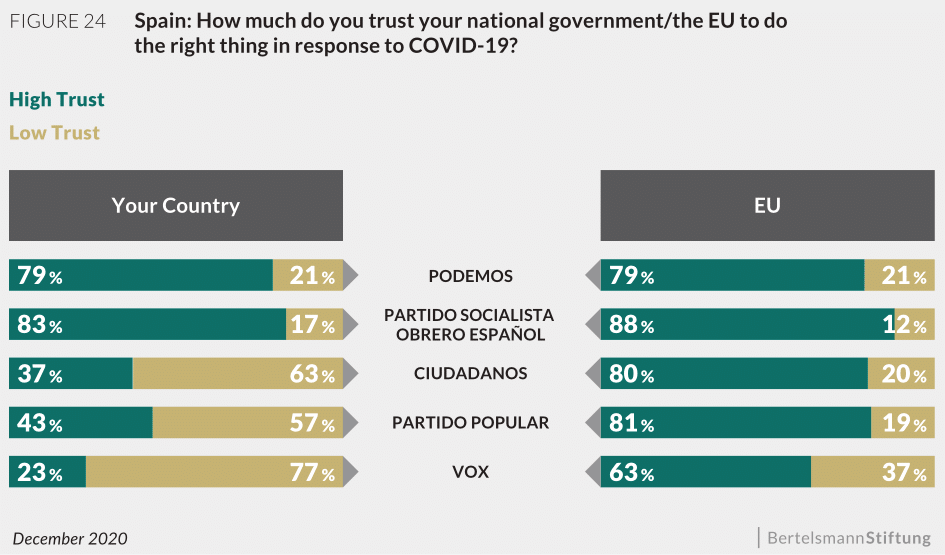

Figure 24 shows that in Spain, supporters of the populist right-wing VOX party are least trusting of their government’s ability to deal with the pandemic (23%). At the same time, most of this cohort has faith in the EU’s ability to deal with the pandemic (63%). Supporters of the ruling party Partido Socialista Obrero Español are the most trusting of their government’s ability to deal with the pandemic (83%), and they express even greater trust in the EU’s ability (88%).

Figure 24

Concluding Remarks

Given the widespread worry in the public debate about further democratic backsliding in the wake of the pandemic, accompanied by the risk of waning public support for health-related restrictions, we examined how European citizens view democracy and the rule of law in this report. Not only did we examine how European citizens evaluate the state of democracy in their country and the EU more generally, but also what they think democracy should be. Our results suggest that citizens attach great value to the rule of law when it comes to democracy. Europeans think that “governments abiding to the law” and “courts treating everyone equally” are two crucial pillars of what characterizes a good democracy. These two factors are not only the most important for the EU27 as a whole, but also for respondents from five of the six countries surveyed individually, namely Belgium, France, Italy, Poland and the Netherlands. Only German citizens consider “free and fair elections” and freedom of expression to be even more important, although these fundamental aspects of representative democracy are also considered very important in the other countries.

Fundamental aspects of representative democracy like free and fair elections and freedom of speech are also viewed to be of key importance. When it comes to evaluating how democracy works, a majority of Europeans is satisfied both with how democracy works in the EU and in their own country. However, it is striking that a full 60 percent of Europeans are satisfied with democracy in the EU, while only 54 percent say the same about democracy in their own country. Beyond that, we also find country-level variation. While Dutch and German citizens are very satisfied with the way democracy works in their countries, only a minority of Spanish, Italian and Polish citizens are satisfied. Poland stands out in two respects. Although only 35 percent of Poles are satisfied with the democracy in their own country, a full 70 percent express positive views on the state of democracy in the EU. These findings feed into the larger narrative that many Europeans welcome the EU as a supervisory agent that’s capable to jump in if individual member states falter.

Another interesting pattern emerges when analysing individually polled countries for respondents with different party affiliations. In general, one finds that those who affiliate themselves with parties on the far-right end of the spectrum are much more sceptical about the state of democracy both within their country and the EU. A notable exception is Poland, where it is exactly the other way around. Supporters of the two most right-wing parties—among them the governing PIS party—are most satisfied about the way democracy works in their country, though least so with how it works in the EU. Supporters of the left-wing Wiosna party, on the other hand, are least happy with the state of democracy in their country.

What about Europeans’ confidence in the EU and their own country to respond appropriately to the ongoing Corona crisis? While 58 percent trust their country’s crisis management, two out of three Europeans (66 percent) have confidence in the EU. Once again, however, there are differences between countries: while Belgians, Germans, Italians and Spaniards trust their country in this respect, only a minority of French (47 percent) and Poles (40 percent) do. Polish citizens, in particular, are hoping for the EU to deal with the pandemic because trust in their own government to deliver an adequate response remains low. When looking at supporters of different parties within countries, one again finds a left-right pattern. Respondents tending towards the far-right end of the political spectrum are significantly less likely to trust both their own country and the EU to do the right thing in response to the ongoing COVID-19 health crisis. Again, Poland sticks out for breaking this pattern in that it is supporters of the left-wing Wiosna opposition party that are least likely to trust their current government to respond appropriately to the pandemic.

Looking back, it is good news that Europeans stand by their democratic values and are largely satisfied with the way it they are implemented, be it on a national or European level, even during a time of crisis. Do these figures imply that there is nothing to worry about when it comes to democracy in Europe? We think not.

The often out of the ordinary survey results from Poland show why. Poles are increasingly dissatisfied with the development of democracy in their country. Their trust in their own government to do the right thing is dropping significantly, and not only in times of pandemic. However, thus far, this general frustration of the Poles with their own leadership has not rubbed off on the EU. On the contrary. Their trust in the EU’s democracy and crisis management is steadily increasing and is clearly above the values of the other countries surveyed individually. This is consistent with our longer-term eupinions trend data, in which a majority of Poles are positive about the direction of the EU and their approval ratings for their country remaining in the EU exceed those of all other countries. In other words, the Polish population is turning towards the EU, hoping that it will compensate for the shortcomings of their own government.

What follows for decision makers in the EU? First, that they are blessed with a leap of faith when it comes to EU citizens’ trust in the EU’s capacity to adequately respond to the ongoing COVID-19 health crisis. This trust is particularly strong in Spain, Poland and France where citizens trust the EU’s crisis management much more than they trust their own government’s one. Notably, this even goes for supporters of far-right parties in France, Italy, Spain and Poland, whose discontent with the pandemic response appears to be largely directed against their own governments. With the EU-organised COVID-19 vaccination rollout having picked up in pace since then, chances are that the EU stands to keep and possibly extend this trust.

At the same time, a majority of European citizens continue to be satisfied with how democracy works in the EU. This observation is also confirmed by our long-term eupinions trend data, where the number of EU citizens’ who are satisfied with the EU’s democracy has risen from 55 percent at the beginning of the crisis (March, 2020) to 59 percent a year later (March, 2021). Having said that, this should not lead us to neglect the challenges to democracy ongoing in individual member sates such as Poland. Just over 1/3 (35 percent) of Polish citizens are satisfied with how democracy works in their country, compared to almost 3⁄4 (70 percent) being satisfied with the EU’s functioning of democracy. Our long-term eupinions trend data confirms this finding, showing an astonishing gap opening up between EU citizens overall satisfaction with democracy in their respective countries (currently 54 percent), and Polish citizens’ trust in their country’s state of democracy (currently 37 percent). Their satisfaction in this regard has dropped from 52 percent to just 37 percent within the last two years.

Our data in this study also shows, however, that European citizens are quite clear about what they think makes for a good democracy. Factors establishing the rule of law rank particularly high on their list of priorities, meaning that, where these are under threat, the EU has reason to count on their citizens support in safeguarding these elements.

References

Anderson, C. J., and Guillory, C. A.. (1997). Political institutions and satisfaction with democracy: A cross-national analysis of consensus and majoritarian systems. American Political Science Review 91(1): 66-81.

Citrin, J. H., McClosky, Shanks, J. M. and Sniderman, P. M. (1975). Personal and political sources of political alienation. British Journal of Political Science (5)1: 31-1.

Dahl, R. (1998). On Democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Easton, D. (1965). A Framework for Political Analysis. Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall.

Easton, D. (1975). A re-assessment of the concept of political support. British Journal of Political Science 5(4): 435-57.

European Parliament. (2020). Rule of law: new mechanism aims to protect EU budget and values. URL: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/eu-affairs/20201001STO88311/rule-of-law-new-mechanism-aims-to-protect-eu-budget-and-values (accessed 20th of January 2021).

Ferrín, M. and Kriesi, H. (ed.). (2016). How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Freedom House. (2020). Freedom in the World 2020: A Leaderless Struggle for Democracy. URL: https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2020-02/FIW_2020_REPORT_BOOKLET_Final.pdf.

Inglehart, R. (2003). How solid is mass support for democracy: and how can we measure it?Political Science and Politics 36(1): 51-7.

Norris, Pippa (ed.). (1999). Critical Citizens. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Reporters Without Borders. (2020). 2020 World Press Freedom Index. URL: https://rsf.org/en/ranking (accessed January 20, 2021).

Rose, R., Doh C. Shin, D. C.and Munro, N. M. I. (1999). Tension between the democratic ideal and reality: the Korean example, in Norris, Pippa (ed.) Critical Citizens. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 146-65.

Shotter, J. (2020). Fears grow for independence of local media in Poland. Financial Times, 17th of December 2020.

V-Dem Institute. (2020). Autocratization Surges–Resistance Grows: Democracy Report 2020, URL: https://www.v-dem.net/media/filer_public/de/39/de39af54-0bc5-4421-89ae-fb20dcc53dba/democracy_report.pdf (accessed 20th of January 2021).

Method

This report presents an overview of a study conducted by Dalia Research for Bertelsmann Stiftung between 2020-12-01 and 2020-12-20 on public opinion across 27 EU Member States. The sample of n=11,857 was drawn across all 27 EU Member States, taking into account current population distributions with regard to age (16–69 years), gender and region/country. In order to obtain census representative results, the data were weighted based upon the most recent Eurostat statistics. The target weighting variables were age, gender, level of education (as defined by ISCED (2011) levels 0–2, 3–4, and 5–8), and degree of urbanization (rural and urban). An iterative algorithm was used to identify the optimal combination of weighting variables based on sample composition within each country. An estimation of the overall design effect based on the distribution of weights was calculated at 1.26 at the global level. Calculated for a sample of this size and considering the design-effect, the margin of error would be 1 percent at a confidence level of 95 percent.