Executive Summary

Over the course of the last decade, we have witnessed a surge in support for euroskeptic parties across European capitals, as well as in Brussels. While the eurozone crisis, followed by increased migration flows from Syria and other parts of the world, are generally seen to have acted as catalysts of euroskeptic party support, the question is whether these parties will be able to do as well in 2019 as in previous elections, or even better. Although it is highly unlikely that euroskeptic parties like Lega in Italy, the Alternative für Deutschland in Germany or the Rassemblement National (formerly known as Front National) in France will gain the upper hand in the election, increased fragmentation and polarization seem to be in the cards for Europe. While polarization is often viewed in ideological terms, that is to say between the political left and right, it can more broadly be seen as indicating major divides in society. The division we highlight in this report is one between those who are hopeful about the state of their society and their own economic position, and those who are fearful about society and their own economic standing. The dividing line between the hopeful and the fearful is important in light of the 2019 European Parliament (EP) election, because – as we will show – it coincides with very different views and preferences regarding European politics and political parties.

Our empirical evidence is based on a survey conducted in December 2018, in which more than 11,000 EU citizens participated. We highlight four main findings:

- First, our evidence suggests that European citizens are deeply divided with regard to how they view society and their own economic position within it. We find a divide between those who are hopeful about society and their economic situation within it, and those who are fearful about these topics. Our findings suggest that within the European Union as a whole, 51 percent of the population is worried about the state of society while 49 percent is not. Similarly, 35 percent of people are economically anxious, while 65 percent are not.

- Second, our evidence indicates that this polarization between the hopeful and the fearful has political implications. The degree to which people are worried about the state of society and are economically anxious is associated with dissatisfaction with the quality of democracy and the direction of policy at the EU level, as well as with the feeling that EU politics are too complicated and fail to take the concerns of ordinary citizens into account. While those who are not worried about society and are not economically anxious tend to be much more satisfied with EU-level democracy and the direction of EU policy, they are also less likely to think that EU politics are too complicated or insufficiently responsive to the concerns of ordinary citizens. Note that we are indicating associations here, not necessarily causal relationships.

- Third, our evidence suggests that in addition to differences in how the hopeful and the fearful view politics at the EU level, there is also considerable overlap between the two groups. A majority of individuals in both groups – roughly 65 percent – intend to vote in the upcoming EP elections, and demonstrate a basic level of knowledge about the European Union.

- Fourth and finally, our evidence shows that those who are fearful are more likely to say that they feel close to populist-right or far-right parties. However, a large share of those who are fearful also say they have no close affinity with any political party. Those in the hopeful group are more likely to say that they feel close to centrist and pro-EU parties. Furthermore, those who are fearful are most likely to think that managing migration, fighting terrorism and securing citizen rights should be the EU’s main policy priorities in the coming years. Interestingly, those who are comparatively more hopeful view some of the same policy areas – specifically fighting terrorism and securing citizen rights – as being important points of focus for the EU in the coming years. However, they also think that fighting climate change should be a top EU priority.

Introduction

The year 2019 will be an important one for the European Union (EU), not only because of Brexit or the possibility of an economic downturn, but also because of the upcoming European Parliament (EP) elections in May. For one, the outcome of the EP elections will be important for the composition of the next European Commission. Since the 2014 EP election, the Spitzenkandidaten process creates a direct relationship between the outcome of the election and the composition of the Commission as the leader of the largest party group will most likely be selected as the new Commission president. The EP must also approve of the new Commission team through an investiture vote. Along with these important institutional factors, the outcome of the election will also be important because it will most likely be judged by commentators and pundits as an important bellwether for future EU political developments. How will La République en Marche, the party led by pro-European French President Emmanuel Macron, do? How much of the vote will the Lega, the Italian party led by euroskeptic Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini, attract? What will all this mean for political cooperation at the EU level, and for the formation of governments at the national level?

Over the last decade, we have witnessed a surge in support for euroskeptic parties both in Brussels and across European capitals. The eurozone crisis and increased migration flows from Syria and other parts of the world are generally seen as catalysts for euroskeptic party support. The question in 2019 is whether these parties will be able to do as well as in previous elections, or even better. Although it is highly unlikely that euroskeptic parties like the Lega, the Alternative für Deutschland in Germany or the Rassemblement National (formerly known as the Front National) in France will be able to gain the upper hand in the election, increased fragmentation and polarization seem to be in the cards for Europe. Many experts are framing the 2019 EP elections as a struggle between pro- and anti-European forces.

What is important to remember, however, is that while various parties might agree on a generally pro- or anti-EU stance, this does not mean they necessarily agree on other issues. Indeed, many issues divide parties even within the euroskeptic and pro-EU camps. Euroskeptic parties are a particularly diverse group. Some are “hard sceptics” that strongly oppose the EU. These parties reject the idea of European integration, and campaign for the renationalization of competencies (Taggart and Szczerbiak 2004, Treib 2014, De Vries 2018). Examples of hard euroskeptic parties include the Rassemblement National in France led by Marine Le Pen, and Geert Wilders’ Partij voor de Vrijheid in the Netherlands. Le Pen has worked to bring her party into the mainstream since taking over from her father in 2011. She is running on an anti-EU, anti-immigration and anti-Islam platform.[1] Like Le Pen, Wilders combines an anti-immigration and anti-EU platform. With slogans such as “taking our country back,” he is actively campaigning for a renationalization of powers ceded to the European Union.[2] Other parties are “soft euroskeptics” that accept the idea of European integration, but demand reform of specific policies or institutions (Taggart and Szczerbiak 2004, Treib 2014, De Vries 2018). Examples of soft euroskeptic parties include Podemos in Spain and Syriza in Greece. Both of these parties rose to electoral power during the eurozone crisis. Podemos mobilized the grievances held by segments of the Spanish population that were suffering under the effects of the economic crisis and the associated austerity measures imposed from Brussels. To an even greater degree, Syriza vocally opposed the austerity policies demanded and enforced by the European Council and Commission. The party’s message resonated strongly with Greek voters, and helped lead the party into government. This great diversity between euroskeptic parties is one of the reasons why cooperation between them within the European Parliament has turned out to be so difficult.

Interestingly, recent academic work suggests that euroskeptic parties have tempered their EU stances in the wake of the crises, especially given the political and economic uncertainty following the Brexit vote (Pirro, Taggart and Van Kessel 2018). Hard euroskeptic parties in particular have become much less likely to advocate for a complete exit from the European Union or the eurozone. The same pattern can be found at the level of individual citizens; since June 2016, survey respondents have increasingly said they support their own home country’s membership in the EU (De Vries and Hoffmann 2016, De Vries 2017, 2018). This might suggest that euroskeptic parties will be unable to garner large-scale electoral support in the upcoming EP election, while indicating that pro-EU parties could do well. However, two points are important to remember here. First, even if people increasingly believe that their countries should remain in the European Union, this does not necessarily mean they are satisfied with the direction being taken by the EU. Not wanting to leave should not be mistaken for wholehearted support for the EU’s current policy direction (De Vries and Hoffmann 2015). Second, EP elections are not only about Europe. Indeed, a large body of scholarly work has demonstrated that EP elections are also used to express discontent with national governments, or used to cast more general protest votes (Van der Brug and Van der Eijk 2007). Many euroskeptic parties harbor and mobilize anti-government and anti-elite sentiment, and will very likely seek to exploit these currents in the upcoming election campaign (Polk and Rovny 2017).

[1] www.theguardian.com/world/2017/feb/05/marine-le-pen-promises-liberation-from-the-eu-with-france-first-policies (accessed 29th of January 2019).

[2] www.pvv.nl/36-fj-related/geert-wilders/9601-heteuropadatwijwillen.html (accessed 29th of January 2019).

Purpose of this Report

In this report, we are not attempting to predict the outcome of the 2019 EP elections. Electoral forecasting is in itself extremely difficult, but is especially so for EP elections, in which turnout rates are notoriously low and national campaigns hinge on very different issues. What we instead aim to do here is provide a tool to help analyze the possible outcomes of the 2019 EP elections – specifically using the lens of polarization. While polarization is often viewed in ideological terms, that is to say between the political left and right, it can more broadly be seen as an indication of major divides within society. The division we highlight here is one between people who are hopeful about the state of their society and their own economic position, and those who are anxious about society and their own economic standing. The dividing line between the hopeful and the anxious is important in light of the 2019 EP election, because – as we will show – it coincides with very different views and preferences with regard to European politics and political parties.

Our empirical evidence is based on a survey conducted in December 2018, in which more than 11,000 EU citizens participated. We highlight four main findings:

- First, our evidence suggests that European citizens are deeply divided with regard to how they view society and their own economic position within it. We find a divide between those who are hopeful about society and their economic situation within it, and those who are fearful about these topics. Our findings suggest that within the European Union as a whole, 51 percent of the population is worried about the state of society, while 49 percent is not. Similarly, 35 percent of people are economically anxious, while 65 percent are not.

- Second, our evidence shows that this polarization between the hopeful and the fearful has political implications. The degree to which people are worried about the state of society and are economically anxious is associated with dissatisfaction with the quality of EU-level democracy and the direction of EU policy, well as with the feeling that EU politics are too complicated and fail to take the concerns of ordinary citizens into account. While those who are not worried about society and are not economically anxious tend to be much more satisfied with EU-level democracy and the direction of EU policy, they are also less likely to think that EU politics is too complicated or insufficiently responsive to the concerns of ordinary citizens. Note that we are indicating associations here, not necessarily causal relationships.

- Third, our evidence suggests that next to differences in how the more hopeful and fearful view politics at the EU level, also considerable overlap between the two groups exists. A majority of individuals in both groups – roughly 65 percent – intend to vote in the upcoming EP elections, and are quite knowledgeable about the EU. A majority of European citizens, whether falling into the hopeful or fearful camp, know that Jean-Claude Juncker is president of the European Commission, and knows which countries are members of the EU.

- Fourth and finally, our evidence shows that those who are anxious are most likely to say that they feel close to populist-right or far-right parties. However, a large share of those who are fearful also say that they do not feel close to any political party. Those in the hopeful group are more likely to say that they feel close to centrist and pro-EU parties. Furthermore, those who are fearful are most likely to think that managing migration, fighting terrorism and securing citizen rights should be the EU’s main policy priorities in the coming years. Interestingly, those who are more hopeful view some of the same policy areas – specifically fighting terrorism and securing citizen rights – as being important points of focus for the EU in the coming years. However, they also think that fighting climate change should be a top EU priority.

Taken together, these findings provide an important lens through which to view the upcoming EP elections. They suggest that one important dividing line in society stems from the degree to which people are hopeful or fearful about the state of society and about their own economic position within it. This resonates with the idea popular among pundits and media commentators that the upcoming election will be a clash between a positive vision for Europe’s future, articulated by French President Emmanuelle Macron and others, and a more skeptical vision expressed by Italian Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini and other such figures. Our evidence suggests that European citizens are polarized when it comes to their levels of hope or fear about their own situations and larger societal trends. Nevertheless, in terms of individual willingness to participate in and to stay informed about the EU, there seems to be considerable overlap. Our findings indicate that a majority of people intend to vote in the upcoming election, and have a degree of basic knowledge about the EU. Many citizens seem willing to participate, and seem to have at least a basic level of knowledge enabling them to do so. Our results also suggest that with the exception of climate change, European citizens agree on what the EU’s core policy priorities should be in the years to come: fighting terrorism and securing citizen rights. These findings indicate that a candidate or political movement able to bridge both sections of society, the hopeful and the fearful, could garner high levels of public support. This conclusion adds new weight to the results of our 2018 eupinions study, Globalization and the EU: Threat or Opportunity?, in which we found that the hopeful were remarkably homogeneous in holding a positive attitude toward European integration, while the fearful were not. Specifically, the latter group was split between those who wanted the EU to provide more protection, and those who rejected the EU altogether.

Are European Parliamentary Elections Actually About Europe?

Although most commentators seem to view the upcoming 2019 election as a campaign between pro- and anti-EU forces, the European issue was long seen as being comparatively unimportant in EP elections. Indeed, scholars have previously conceived of EP elections as second-order national elections (Reif and Schmitt 1980, Van der Eijk and Franklin 1996, Van der Brug and Van der Eijk 2007). Given that EP powers are fairly limited compared to those held by national parliaments, this perspective regarded EP elections as being less important than national elections in the eyes of voters, who used the former largely as a way to express their approval of or disappointment with national governments. However, against the backdrop of rising public concern about the EU project and the extension of EP powers, recent evidence suggests that EU concerns do in fact affect vote choices (Clark and Rohrschneider 2009, Hobolt et al. 2009, De Vries et al. 2011, Hobolt and De Vries 2016b). For example, research has found that one key reason why voters may defect from governing parties in EP elections is because these parties hold positions that are more strongly pro-EU than are their voters (Hobolt et al. 2009). Voters possessing high levels of political information in particular use attitudes toward the EU to guide their vote choices in EP elections (De Vries et al. 2011); however, knowing more about the EU does not necessarily mean that they back strongly pro-EU parties (Marquant et al. 2018).

The growing involvement of EU institutions in national policymaking, especially during the eurozone crisis, is perceived as one of the main reasons why EP elections are increasingly turning on people’s views about Europe (Hobolt and De Vries 2016a). For example, citizens today are less likely than previously to think that their own government is solely responsible for national economic outcomes, and have instead shifted a portion of blame to the EU (Hobolt and Tilley 2014). Indeed, given that the 2014 EP elections were held against the backdrop of the eurozone crisis, with the EU itself becoming an object of blame in the popular discourse, many citizens expressed their discontent by casting a ballot for a euroskeptic party (Hobolt and De Vries 2016b). This short review of the scholarly work on voting behavior in EP elections suggests that European matters have increasingly become an influential factor within European elections, but that they are clearly not the only such factor. Disagreement with the EU’s policy direction, disapproval of a national government’s overall stance on Europe and disappointment with a national government’s record more generally can all be major forces driving voter decision-making in EP elections. EP elections have increasingly become an arena where voters can express their discontent with European and national politics alike.

Polarization as a Prism for Understanding the 2019 EP Elections

In Focus

As stated earlier, we are making no attempt here to predict the outcome of the 2019 EP elections. This is in part because electoral forecasting is increasingly difficult as party loyalties weaken (Wattenberg and Dalton 2000), especially in relation to the EP. Given that EP elections are perceived by voters as being less important than national elections, and less consequential for the composition of the executive branch (Reif and Schmitt 1980, Van der Eijk and Franklin 1996, Van der Brug and Van der Eijk 2007), turnout is a key issue. However, turnout rates are also hard to predict. This additionally makes it very difficult to evaluate which parties are more or less likely to be affected by changes in these rates. Yet while we do not seek to predict the outcome, we do want to provide deeper insights into key developments that might shape this election outcome. As we have demonstrated in previous reports, including Fear Not Values (2016), Globalization and the EU and The Power of the Past (2018), the European public is deeply divided in how they view the world around them. Here we aim to delve deeper into these divides by focusing on two sources of polarization: people’s worries about the state of society, and their anxieties regarding their own position within society. We understand polarization as being a sharp division between elements of the population that produces opposing factions (Lipset 1960, Schnattschneider 1960). While this is often viewed in ideological terms, that is to say between the political left and right, it can more broadly be seen as an indication of major divides in society. Sources of societal division can be especially important, as the terms “left” and “right” have lost some of their prescriptive power in recent years, with many debates on the state of society focused on issues such as immigration, cultural values or LGTB rights (De Vries, Hakhverdian, Lancee 2013, Norris and Inglehart 2018, Abou-Chadi and Finnegan 2019). In this research, we focus on polarization based on people’s assessment of the state of their society and their own position within it. These two aspects of polarization capture what political scientists refer to as sociotropic and pocketbook evaluations. Sociotropic evaluations relate to assessments about the state of world, while pocketbook evaluations relate instead to assessments of the way an individual (or household) is situated within that world (Kramer 1971). While scholars have traditionally argued that personal circumstances have less influence on voting decisions and turnout rates than do sociotropic economic evaluations (Kinder and Kiewiet 1979, Fiorina, 1978), there has recently been something of a revival of pocketbook approaches to electoral behavior. A series of studies has suggested that personal economic circumstances in fact have a significant effect on electoral behavior and political preferences. Voters respond to specific policies that have direct consequences for their own welfare, such as disaster relief or cuts in social expenditure, by adjusting their political preferences and voting choices (Bechtel and Hainmueller 2011, Healy and Malhotra 2010, Margalit 2013). Likewise, economic self-interest is found to be a key determinant of welfare preferences, with income, employment risk and degree of dependence on social protection being strong predictors of attitudes redistribution (Rehm 2011, Hacker et al. 2013).

Against this backdrop, we are interested in the degree to which differences in how people view the state of society – that is, whether they are worried about it or not – and in how they evaluate their own economic position – again, whether they are anxious or not – matter for political preferences. What we label here as polarization refers to the degree to which people diverge in their views of the state of society and their own economic position. While there are of course many different roots of societal division, for example based on rural or city residence, cultural values, or class (Cramer 2016, Norris and Inglehart 2018, Evans and Tilley 2017), we contend that these two aspects – people’s views about the state of society and their assessment of their position in it – are also important. They feature heavily in current political discourse, for instance in the populist narratives of societal and personal decline, and in high-profile societal protests, as in the Yellow Vest movement in France. Specifically, we distinguish between those who are fearful about the state of society and their own economic position in it, and those who are hopeful about these topics. We suggest that this distinction might play a role in shaping people’s preferences about European politics, the party they feel most close to, and the priorities they think the EU should be pursuing in the years to come.

However, it can be difficult to provide empirical insight into the ways in which Europe’s citizens are divided in terms of their societal worries and economic anxieties. Measuring these concepts in a survey is a far from straightforward task, and many different authors have taken different approaches. No convention has yet been established with regard to measuring people’s anxieties about the state of society or their own positions within in. We thus aim to be entirely transparent regarding the choices we have made. Specifically, we have relied on the following questions to capture people’s worries about the state of society and their level of personal economic anxiety.

The measure of worry about the state of society combines answers to two questions:

- To what extent do you agree with the following statement: The world used to be a better place.

- Think of today’s children. Compared to their parents, do you think they will be better off, worse off, or the same?

The measure of personal economic anxiety also combines answers to two questions where 1 is coded negative and 0 is coded positive:

- How has your personal economic situation changed in the last two years?

- In general what is your personal outlook on the future?

Those who think that society used to be better and/or that today’s children are worse off are regarded as being worried about the state of society. Those who think that their personal economic situation has become worse over the last two years and/or are pessimistic about their personal outlook are categorized as being economically anxious. For ease of interpretation, all measures used in the analysis are coded between 0 and 1 so the numbers in the tables and graphs can be interpreted as proportions through percentages.

Figure 1 and figure 2 provide an overview of the shares of people who can be classified as societally worried and economically anxious – that is, the fearful – versus those who are hopeful about society and their own economic position. It indicates these shares for the EU27, that is to say the current EU member states without the United Kingdom, along with six individual member states including France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland and Spain.

Figure 1 indicates that citizens across the EU27 are tremendously divided with regard to their views about the state of society, with 51 percent expressing worry on this topic, and 49 percent feeling more sanguine. We find a similar distribution in France, where 51 percent are worried about society, and 49 are not. In Italy and Poland, respective majorities of 65 percent and 56 percent are worried about the state of society, while 35 percent of Italians and 44 percent of Poles are not worried. In Germany, the Netherlands and Spain, a minority of respondents are worried about the state of society. Only 38 percent of Germans are worried, while 62 percent are not. A respective total of 47 percent and 45 percent of Dutch and Spanish respondents are worried about the state of society, while 53 percent and 55 percent of Dutch and Spanish respondents are not.

Figure 2 provides an overview of the share of respondents who are or are not economically anxious. The level of polarization is also considerable when it comes to personal economic anxiety, but is less pronounced overall than is true of people’s views about society at large. A total of 35 percent of respondents in the EU27 can be classified as economically anxious, while 65 percent are not. The figure shows interesting differences across countries. France in particular stands out with a majority of 62 percent of respondents classified as economically anxious, and 38 percent as more confident. Italian respondents are also slightly more economically anxious than the EU27 average. A total of 40 percent of Italian respondents are economically anxious, while 60 percent are not. A third of Spanish respondents classify as economically anxious, while 67 percent do not. Finally, the lowest levels of economic anxiety can be found in Germany, the Netherlands and Poland, where only 27 percent (for the first two countries) and 24 percent of respondents (in Poland) are respectively economically anxious.

Overall, these figures suggest that there is a considerable share of people – as much as one-third to one-half of the population – who are anxious about the state of society and their position within it. Yet at least one-half, and perhaps even a majority of European citizens are hopeful about society and their own position in it. Next, we examine how these different groups in society, the hopeful and the fearful, each view EU politics.

People’s Views About EU Politics

In this section, we explore different aspects of people’s views about European politics. Specifically, we will examine seven aspects:

- People’s intention to vote in the 2019 EP election

- Familiarity with the concept of Spitzenkandidat,

- People’s knowledge about the EU

- People’s views as to whether EU politics are too complicated

- People’s views as to whether the EU takes ordinary citizens’ concerns into consideration

- People’s views as to whether the EU is moving in the right direction

- People’s satisfaction with democracy at the EU level

These various aspects reflect what political scientists have traditionally called political efficacy (Almond and Verba 1963, Easton and Dennis 1967). Political efficacy captures the extent to which people think their political participation will be effective - that is, the belief among citizens that the political system serves their interests in the best possible way, and that politicians are doing the most they can to ensure this. Political efficacy may present itself in either an internal or external form. While internal efficacy relates to the belief that the individual understands the political system and has the ability to affect it, external efficacy is associated with the feeling that politicians pay attention to citizen demands and respond accordingly (Converse 1972, Craig 1979). Political efficacy is clearly important, as individuals might not bother participating politically if they believe such action will make no difference. Having a sense of political efficacy is connected with people’s emotional links to the political system and their experiences with it (Easton and Dennis 1967). While a sense of political efficacy captures the extent to which people think they can affect political outcomes through engagement in the political process, for instance in the context of an election, feelings of powerlessness might in contrast lead citizens to feel politically alienated, prompting them to withdraw altogether from political participation. These processes are complex and most likely reciprocal, with higher levels of political efficacy being associated with more participation, and participation in turn helping to increase feelings of political efficacy (Finkel 1985). We aim here to establish relationships and associations, not determine causality.

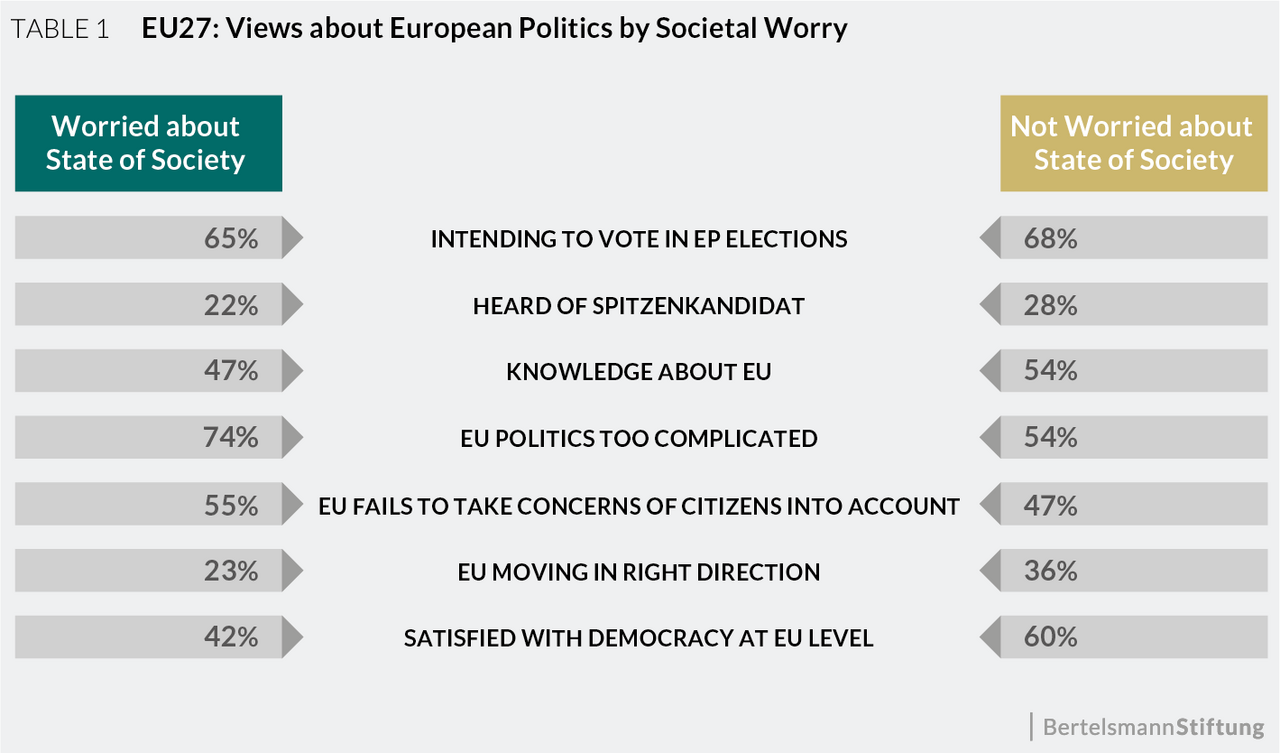

Table 1 compares views about European politics between those who are worried about society and those who are not. The table shows some interesting differences and similarities between the two groups. As a start, the groups differ very little with regard to the intention to vote in the 2019 EP elections, with 65 percent of those who are worried about society intending to cast a ballot in the 2019 EP elections, along with 68 percent of those who are not worried. Similarly, we find only small differences with regard to familiarity with the lead-candidate concept or more general knowledge about the European Union. While 28 percent of those who are not worried about the state of society have heard of a Spitzenkandidat, 22 percent of those who are worried have done so. A total of 54 percent of those who are not worried about society demonstrate a basic knowledge about the European Union, while 47 percent of those who are worried do so. We measure this knowledge based on two items, the first of which asked people who the current Commission president was, the second of which asked whether certain countries were members of the EU or not. The largest differences between the two groups emerged with regard to people’s perceptions that EU politics are too complicated, and the question of whether the EU takes the concerns of ordinary citizens into account. A majority of 74 percent of those who are worried about society think that EU politics are too complicated, while 55 percent of this group thinks that the EU does not take the concerns of ordinary citizens into account. These shares are much lower among those who are not worried about the state of society, with a respective 54 percent and 47 percent thinking that EU politics are too complicated and that the EU fails to take the concerns of citizens into account. Those who are worried about society are also much less satisfied with EU-level democracy and the direction of EU policy than those who are not worried.

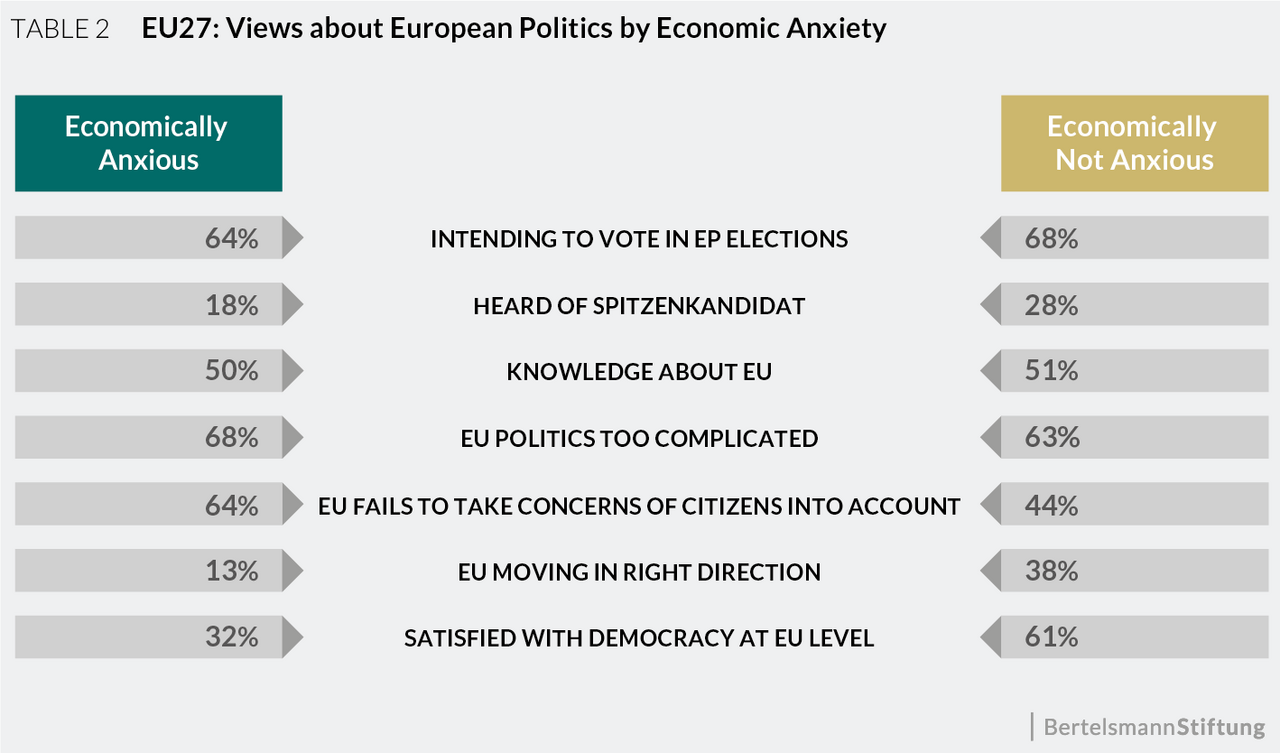

Table 2 compares the views about European politics between those who are and are not economically anxious. Here too, we find some interesting differences and similarities between those who are economically anxious and those who are not. As in the case of people’s societal-worry categorizations, the two groups differ very little when it comes to the intention to vote in the 2019 EP elections; 64 percent of those who are economically anxious intend to cast a ballot in the 2019 EP elections, while 68 percent of those who are not anxious say they will turn out to vote. When it comes to being knowledgeable about the EU, we also find only small differences: 50 percent of those who are economically anxious express a basic level of accurate knowledge about the EU, compared to 51 percent of those who are more confident. People’s views about the complicated nature of EU politics also show smaller differences than were evident in Table 1. Here, 68 percent of those who are economically anxious believe EU politics are too complicated, while 63 percent of those who are not economically anxious hold this opinion. The different economic-anxiety groups show greater variation regarding familiarity with the Spitzenkandidat concept than do the societal-worry groups. While 28 percent of those who are not economically anxious have heard of a lead candidate, only 18 percent of those who are anxious have. The biggest differences between the two groups appear with regard to people’s perceptions of the degree to which ordinary citizens’ concerns are taken into account in EU politics, the extent to which people are satisfied with the direction the EU is taking, and their feelings about the state of EU democracy. A majority of 64 percent of those who are economically anxious thinks that the EU does not take the concerns of ordinary citizens into account. This share is much lower among those who are not economically anxious, with only 44 percent thinking that the EU fails to take citizens’ concerns into account. Those who are economically anxious are also much less satisfied with EU-level democracy and the direction of EU policy than those who are not anxious. Only 13 percent of the economically anxious agree that the EU is moving in the right direction, while 32 percent of this group is satisfied with democracy at the EU level.

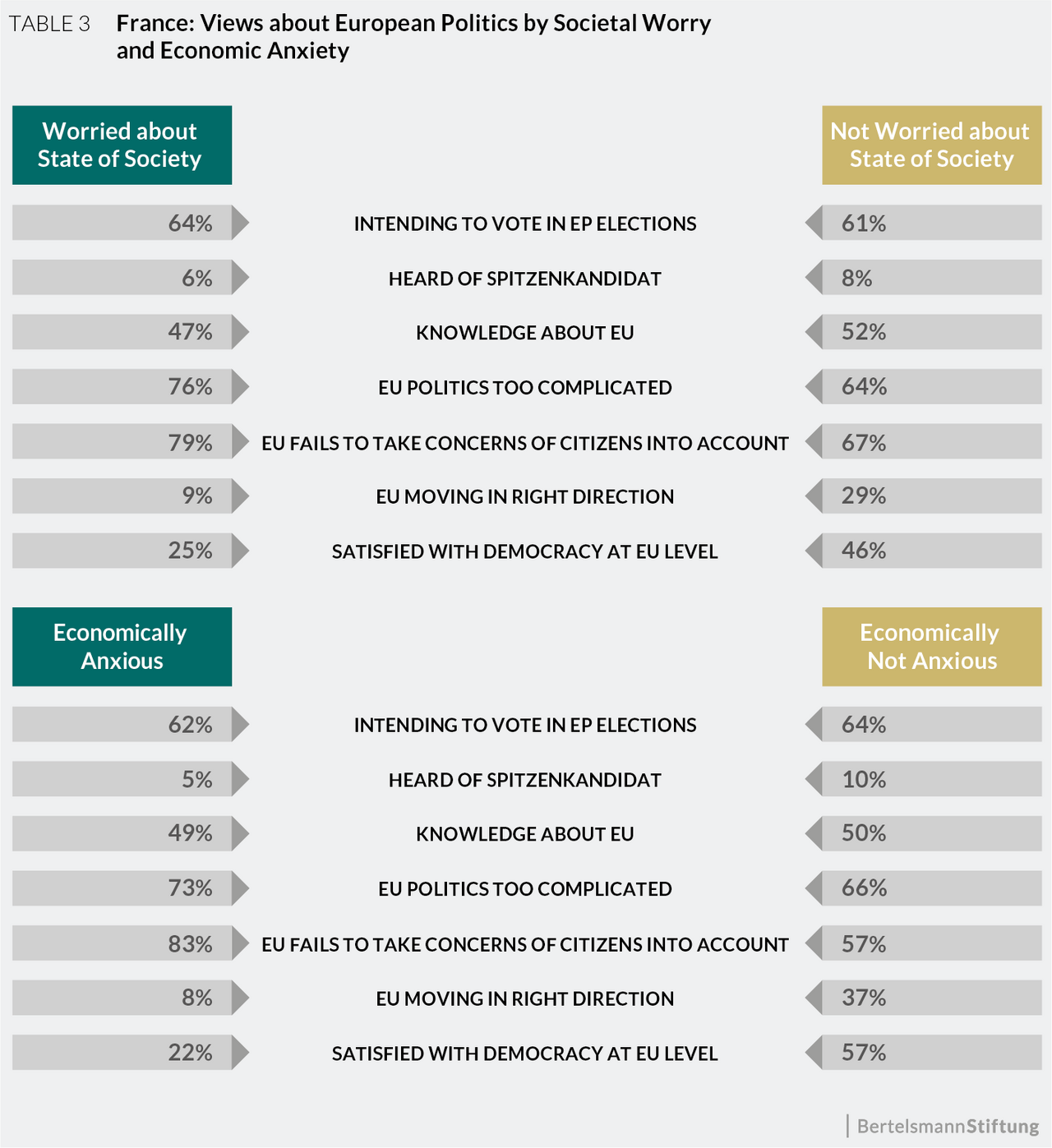

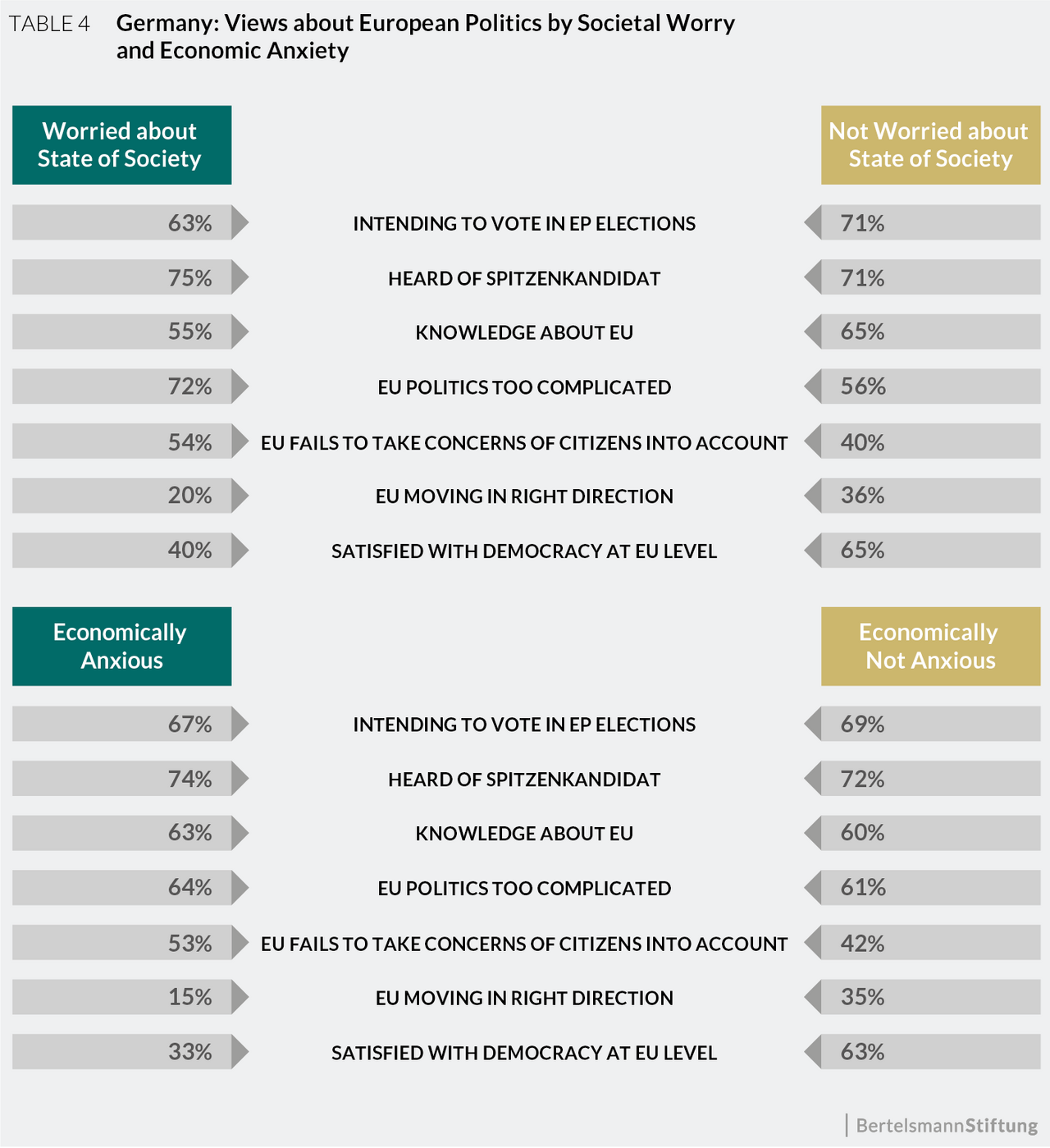

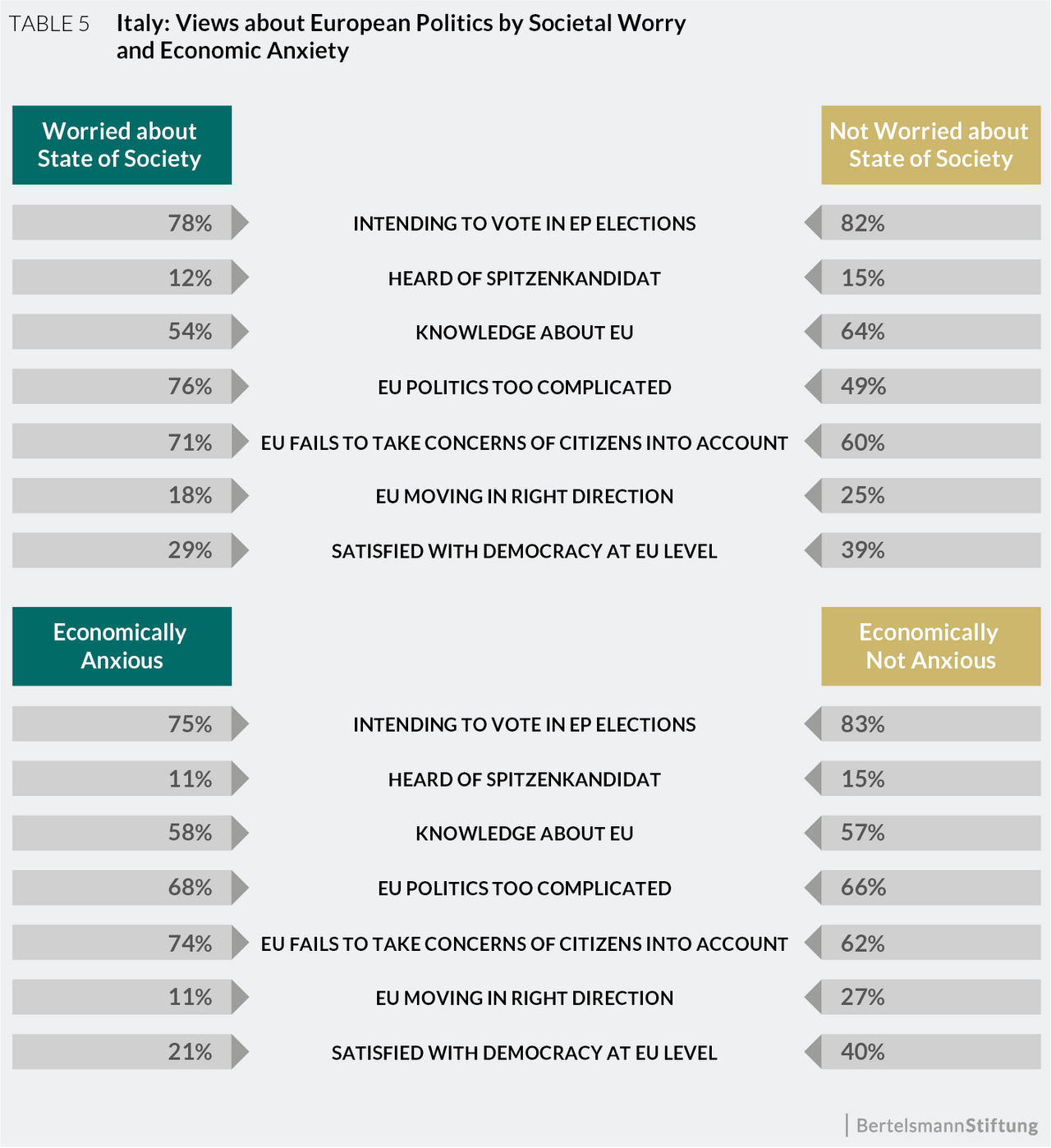

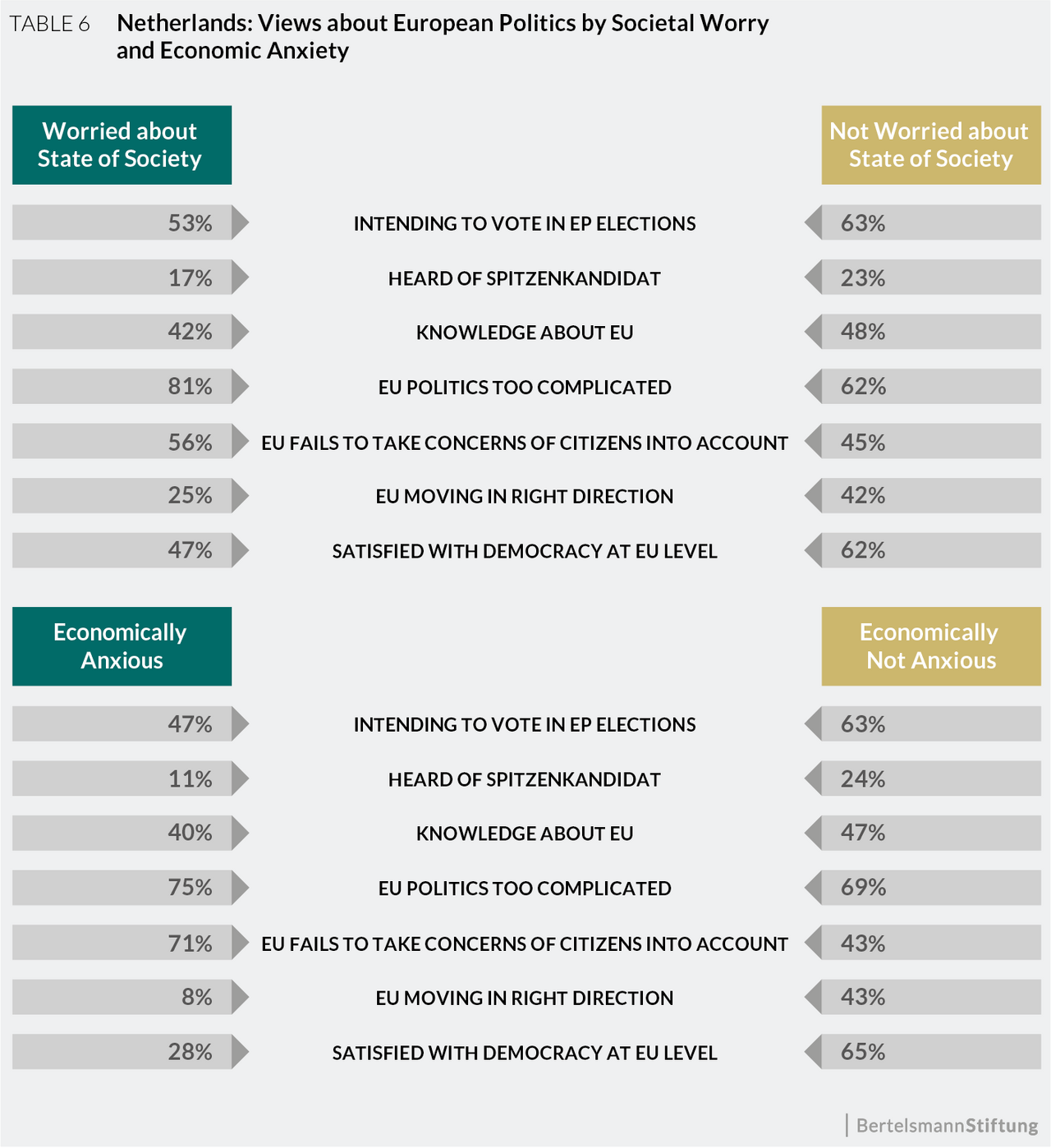

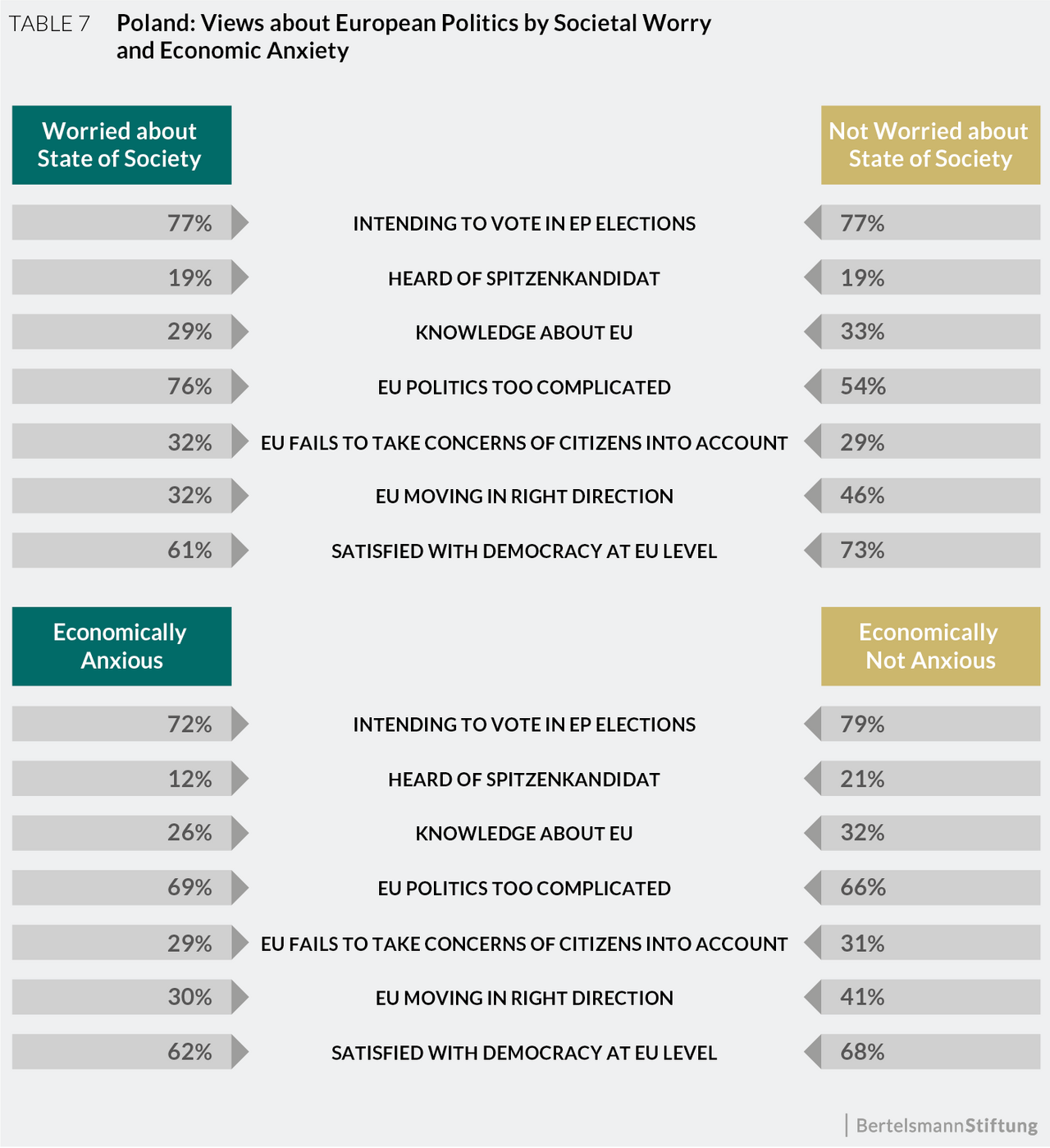

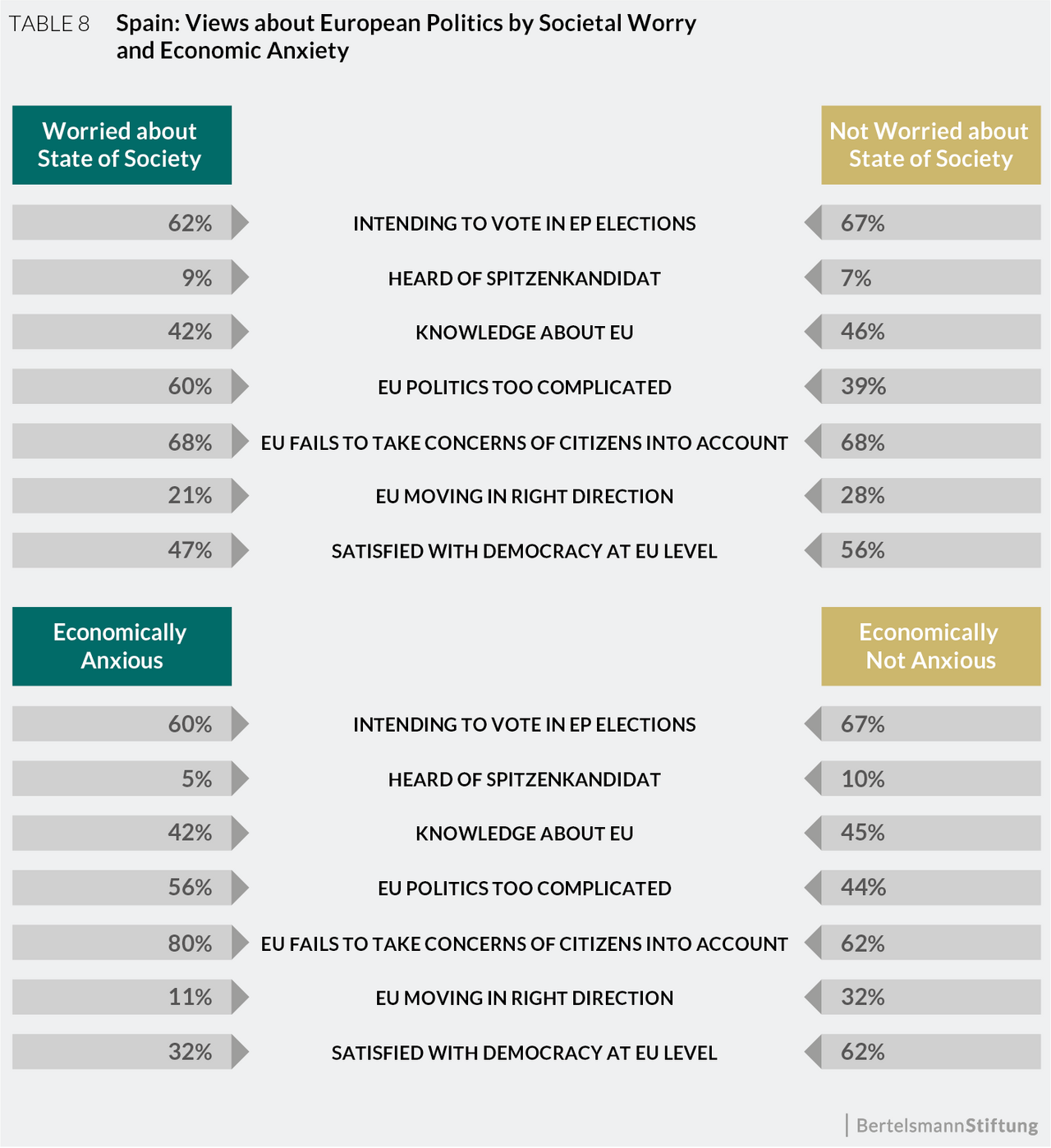

Tables 3 through 8 provide the same type of information, this time split up among the six individual countries. By and large, they reflect the same patterns evident within the EU27 as a whole. Those who are anxious about the state of society or their own economic position differ little from those who are hopeful with regard to voting intentions or their degree of basic knowledge about the EU. Yet the two groups - the fearful and hopeful - differ greatly with regard to perceptions of how complicated EU politics are and how little the EU takes ordinary citizens’ concerns into account, as well as with respect to their degree of satisfaction with EU-level democracy and the EU’s overall policy direction. Interestingly, yet not surprisingly, what clearly stands out for Germany in Table 4 compared to the rest of the countries is the degree to which German respondents are familiar with the Spitzenkandidat concept. Roughly three-quarters of German respondents, no matter what their degree of anxiety or hope about the state of society or their own standing in it, were familiar with the concept. In all other countries, this share was much lower.

Taken together, this evidence suggests that by-and-large those respondents who are fearful about the state of society or their own economic position feel less politically efficacious in EU politics compared to those who feel more hopeful. However, there are far fewer differences with regard to the intention to vote within the EP elections or respondents’ level of basic EU knowledge. This suggests that the polarization we have identified here may indeed play a role in the 2019 EP elections, as most citizens intend to vote whether they feel anxious or hopeful. In the next section, we turn to the question of respondents’ political-party affinities.

Political-Party Affinities

Which political parties do people feel close to? This is the question we turn to next. We first provide an overview of respondents’ party affinities in general, and then in a subsequent step, take a closer look at party affinities among those falling respectively into the anxious and hopeful groups. Figure 3 (3.1., 3.2., 3.3., 3.4., 3.5., 3.6.) provides an overview of party affinities in the six countries we examine on an individual basis, including France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland and Spain. Several interesting findings stand out here. First, in France, the largest share of respondents − 49 percent, to be specific − do not feel close to any party. Among respondents that do feel some degree of party affinity, 14 percent feel close to Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National, while a bit more than half that amount, or 8 percent, feel close to President Emmanuel Macron’s La République En Marche. In Germany, while 23 percent of people feel close to no party at all, affinities for the parties currently represented in the German Bundestag are quite evenly distributed. A total of 10 percent feel close to the Alternative für Deutschland, 14 percent feel close to the Greens, and 16 percent feel close to Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrat party. In Italy, we find that most respondents feel close to one of the two parties currently in government, either the Lega, at 26 percent, or the Movimento Cinque Stelle, at 28 percent. In the Netherlands, 14 percent of respondents feel close to Geert Wilders’ Partij voor de Vrijheid, closely followed by 13 percent for Prime Minister Mark Rutte’s Liberal Party and 11 percent for the Greens. Here too, a considerable share of 19 percent of people feels close to other, unlisted parties. In Poland, the largest shares of respondents feel close either to the ruling Law and Justice party (PiS, with 29 percent), or to no party at all (30 percent). In Spain too, the largest share of respondents feel close to no party (30 percent), followed by other unlisted parties (20 percent), and the Social Democratic party currently headed by Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez (15 percent).

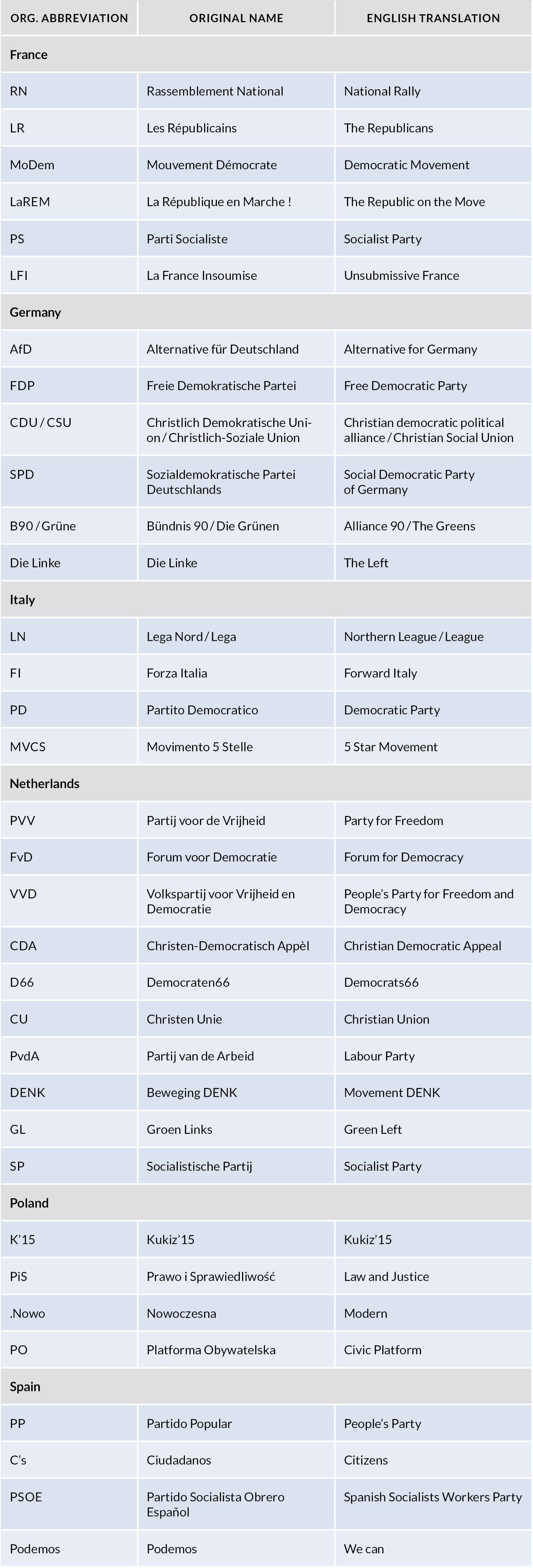

In the following, we explore people’s responses in greater detail, examining differences between those who feel anxious and those who feel hopeful about the state of society and their own economic positions. This information is contained in figures 4 (4.1., 4.2., 4.3., 4.4., 4.5., 4.6.) and 5 (5.1., 5.2., 5.3., 5.4., 5.5., 5.6.). Again, several interesting findings stand out. In virtually all of the countries under investigation, we find that those who feel an affinity for right-wing parties, especially parties on the populist right, display higher levels of societal worry. Such parties include the Rassemblement National (RN) in France, the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) in Germany, the Lega in Italy, the Partij voor de Vrijheid (PV) in the Netherlands, the Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (Law and Justice Party; PiS) in Poland, and the Partido Popular (PP) in Spain. We find a clearer pattern for societal worries in this respect than economic anxiety. Levels of economic anxiety are also pronounced among those who feel close to populist-left parties, which include the Socialist Party (SP) in the Netherlands, Die Linke in Germany, Podemos in Spain, and Jean-Luc Melenchon’s La France Insoumise (LFI) movement in France. This evidence underscores conclusions made in our previous report, Fear Not Values, in which we found that economic anxiety and globalization fears in 2016 coincided with greater support for populist parties on both the left and the right of the political spectrum. Figures 4 and 5 also suggest that those who feel close to centrist parties, such as La République En Marche in France or the Christian Democratic parties in Germany and the Netherlands (respectively the CDU and CDA), display less societal worry and economic anxiety.

Respondents’ Policy Priorities for the EU

In a final step, we review respondents’ responses to a question in which they were asked which policy priorities should be most important for the EU in the coming years. Figure 6 provides an overview of responses within the EU27. It indicates that respondents overall feel that protecting citizens’ rights (17 percent), fighting terrorism (16 percent) and stopping climate change (15 percent) should be the EU’s key priorities. Figure 6 also provides the same type of information for the six countries examined in greater depth. These results suggest that fighting terrorism is perceived to be the top-priority issue among French respondents (18 percent), followed by protecting citizen rights (15 percent). In Germany, stopping climate change (21 percent) is perceived as being the EU’s top priority. In Italy, the Netherlands, Poland and Spain, protecting citizen rights is perceived as being the EU’s top priority, supported by 20 percent to 25 percent of respondents.

In Figure 7 we show the distribution of policy priorities based on the previously distinguished categories of societal worry and personal economic anxiety. The main differences between those who are fearful and those who are hopeful relate to the importance attributed to managing migration and stopping climate change. While those who are worried about the state of society or their own economic position within it view managing migration as a top priority for the EU (with a respective 16 percent and 15 percent choosing this option) along with protecting citizens’ rights and fighting terrorism, those who are more hopeful place a similar or even stronger priority (19 percent for those who are hopeful about society, and 15 percent for those hopeful about their own position) on the need for the EU to fight climate change. That said, the fearful and hopeful agree on the importance of protecting citizen rights.

In a final step, we ask what are the policy priorities for those who feel close to particular political parties? These results are shown in figures 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13. Interestingly, in France we see that supporters of both the populist-right and centrist parties think that fighting terrorism should be a key priority for the EU in the years to come. However, for those who feel close to the centrist La République En Marche, climate change is equally important, while this is clearly not the case for those who feel close to the Rassemblement National. In addition, those who feel close to La France Insoumise think that climate change is a key priority, but do not identify terrorism or migration as such. In Germany, those who feel close to the Alternative für Deutschland view managing migration as the core issue for the EU in the coming years, with fully 40 percent viewing this issue as a top priority. Among those who feel close to Die Linke, stopping climate change is identified as the highest priority (receiving a 25 percent share), while those who feel close to Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrat party by contrast lean toward securing peace (23 percent). In Italy, those who feel close to the Lega, Forza Italia or the Movimento Cinque Stelle all think that protecting citizen rights should be the EU’s key priority, while those close to the Lega and Forza Italia also view managing migration as a top policy issue. Protecting citizen rights is also viewed as a key priority among Dutch respondents, especially for those who support Geert Wilders’ Partij voor de Vrijheid (PV), the Liberal Democrats (D66) or the Christian Union (CU). For those close to Wilders’ party or the Christian Union, fighting terrorism is also perceived to be a key EU policy priority. Climate change is seen as a key priority for those close to D66, the CU and the Greens (GL). For those close to the Polish governing party, Law and Order (PiS), fighting terrorism and managing migration are seen as the key policy priorities. Among Spanish respondents, regardless of what party they feel close to, protecting citizen rights is viewed as the top priority for the EU in the coming years.

Concluding Remarks

Over the course of 2018, an intense strategic debate was happening between the political powerful and government insiders. Given the rise of popular discontent and populist challenger parties across the Union, the demand for creative, practicable solutions on how to handle if not to solve this crisis of democratic representation was high. Particularly worrisome seemed the prospect of a European parliament in which no operative majority could be constituted. Nearly as bad would be a majority so thin that the forces of the political center constituting it would be bound together as if they were one, leaving radical forces on the extreme and/or populist right or left as the only viable political alternatives. Among leading figures in European policy circles, two strategic options were on the table. Let’s call them: productive disruption and enhanced continuity.

The first camp was led by French President Emmanuel Macron, while the second included a surprisingly diverse cross-section of the European political establishment. The former argued that the political landscape had fundamentally changed, with new cleavages now influencing electoral choices. Consequently, the structure in which the political arena was set up needed to adapt to this new reality if it were to survive. Left / right is over; open / closed is the new name of the game, they claimed. The latter, less convinced, insisted that in times of crisis continuity was key. And continuity they could do. Keep the ship steady, they replied. This storm will blow over. We are doing better than people realize. They will come around. Also, by shifting from a left / right dimension to an open / closed one, populist actors would move from the fringes of the system to its very center. Promote them in order to beat them? That does not sound right. And so the arguments went back and forth for months.

How does this report shed light on this debate? This report is intended to shed light on the upcoming 2019 EP election by highlighting the polarization that has taken place within the voting population. Specifically, we are examining a particular manifestation of polarization - that is, the degree of divergence in how people view the state of society and their own economic position. These two factors play a key role in present-day political discourse, and in much societal protest. We distinguish between those who are fearful and those who are hopeful, and show that this distinction matters with regard to people’s opinions about European politics, their political-party affinities, and their preferences regarding EU policy priorities for the coming years.

In reviewing our eupinions public-opinion data from December 2018, we highlight four key findings:

- The European public is deeply divided about how they view society and their own economic position within it: 51 percent of respondents in the EU27 are worried about the state of society, while 49 are not, and 35 percent are economically anxious, while 65 percent are not.

- This division between the hopeful and the fearful has political implications. Those who are anxious are also dissatisfied with EU-level democracy and the EU’s policy direction. Moreover, they view EU politics as being too complicated, and believe that the EU fails to take the concerns of ordinary citizens into account. By contrast, those who are hopeful are largely satisfied with EU-level democracy and the EU’s policy direction, and are less likely to think that EU politics are too complicated or insufficiently responsive to the concerns of ordinary citizens.

- There are also similarities between the two groups. For example, a majority in both groups expressed an intention to vote in the upcoming EP elections, and is knowledgeable about the EU.

- Finally, our evidence indicates that those who are anxious are more likely to say that they feel close to populist-right or far-right parties, or to deny having an affinity with any political party. Those who are more hopeful are more likely to say that they feel close to centrist and pro-EU parties. Those who are fearful identify managing migration, fighting terrorism and securing citizen rights as the most important policy priorities for the EU in the coming years. Those who are more hopeful also view fighting terrorism and securing citizen rights as key issues for the EU, but additionally cite fighting climate change as a top priority.

Taken together, these findings provide an important prism through which to view the upcoming EP elections. They indicate that the degree to which people are hopeful or fearful about the state of society and their own position within it draws a significant and influential dividing line through society. The political offer that fits this demand is an open worldview promoting a cooperative pro-European integration stance versus a closed one with an emphasis on competing interests and national specificities.

This fits with the analysis put forward by French President Macron - which has been strongly echoed by pundits and media commentators, but questioned by established political leaders on the center-left and center-right - that the upcoming election will be a clash between a positive vision for Europe’s future and a more skeptical one. Was the Macron camp right, after all? Our evidence certainly points in that direction. While we cannot comment on the structural conclusions drawn by the Macron camp, e.g. the claim that the political center should reorganize itself before it collapses under pressure from the “fringes” as witnessed in France, our latest evidence bolsters the suggestion found in earlier eupinions reports: that political parties in the coming electoral campaign would be ill-advised not to be open about their vision for the future of the European Union and their policy solutions for European issues. This is rendered all the more critical by the fact that earlier eupinions data has indicated that the hopeful are quite homogeneous with regard to their attitude toward democracy, society and European integration, while the fearful are not. Instead, the fearful are split between a group that follows a generally nationalistic logic, and another that expects European politics to cater more specifically to their concerns (De Vries and Hoffmann 2018).

Most interestingly, our evidence suggests that European citizens are polarized in a 50/50 fashion with regard to their levels of hope or fear about their own economic circumstances and larger societal trends. Yet there seems to be considerable overlap in terms of their willingness to participate in EU-related political processes, and to stay informed about the EU. Our data shows that a majority of people, whether fearful or confident, both intend to vote in the upcoming election and have a solid degree of basic knowledge about the EU. Our results also show that European citizens largely agree that the EU should place a strong priority in coming years on fighting terrorism and securing citizen rights, although the hopeful population also believes that climate change should be a key priority.

Finally, these findings allow us to point out that a candidate or political movement that could build bridges between these segments of society - the hopeful and the fearful - would have the ability to garner high levels of public support, potentially winning what is likely to be another close race for the power to shape our future.

Glossary

References

Abou-Chadi, T., and Finnegan, R. (2019). Rights for Same-Sex Couples and Public Attitudes Toward Gays and Lesbians in Europe. Forthcoming in Comparative Political Studies.

Verba, S., and Almond, G. (1963). The Civic Culture. Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations. Boston: Little, Brown.

Bechtel, M. M., and Hainmueller, J. (2011). How lasting is voter gratitude? An analysis of the short-and long-term electoral returns to beneficial policy. American Journal of Political Science, 55(4), 852–868.

Clark, N., and Rohrschneider, R. (2009). Second‐order elections versus first‐order thinking: How voters perceive the representation process in a multi‐layered system of governance. European Integration, 31(5), 645–664.

Converse, P. E. (1972). Change in the American electorate. The human meaning of social change. Russell Sage Foundation, 263–337.

Craig, S. C. (1979). Efficacy, trust, and political behavior: An attempt to resolve a lingering conceptual dilemma. American Politics Quarterly, 7(2), 225–239.

Cramer, K. J. (2016). The politics of resentment: Rural consciousness in Wisconsin and the rise of Scott Walker. University of Chicago Press.

De Vries, C. E. (2017). Benchmarking Brexit: How the British decision to leave shapes EU public opinion. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 55, 38–53.

De Vries, C. E. (2018). Euroscepticism and the Future of European Integration. Oxford University Press.

De Vries, C. E., and Hoffmann, I. (2015). What Do the People Want. Opinions, Moods and Preferences of European Citizens. eupinions. <link de text what-do-the-people-want>eupinions.eu/de/text/what-do-the-people-want/

De Vries, C. E., and Hoffmann, I. (2016). Fear Not Values: Public Opinion and the Populist Vote in Europe. eupinions. <link de text fear-not-values>eupinions.eu/de/text/fear-not-values/

De Vries, C. E., and Hoffmann, I. (2018). Globalization and European Integration: Threat or Opportunity? eupinions. <link de text globalization-and-the-eu-threat-or-opportunity>eupinions.eu/de/text/globalization-and-the-eu-threat-or-opportunity/

De Vries, C. E., Hakhverdian, A., and Lancee, B. (2013). The dynamics of voters’ left/right identification: The role of economic and cultural attitudes. Political Science Research and Methods, 1(2), 223–238.

De Vries, C. E., Van der Brug, W., Van Egmond, M. H., and Van der Eijk, C. (2011). Individual and contextual variation in EU issue voting: The role of political information. Electoral Studies, 30(1), 16–28.

Easton, D., and Dennis, J. (1967). The child's acquisition of regime norms: Political efficacy. American Political Science Review, 61(1), 25–38.

Evans, G., and Tilley, J. (2017). The new politics of class: The political exclusion of the British working class. Oxford University Press.

Finkel, S. E. (1985). Reciprocal effects of participation and political efficacy: A panel analysis. American Journal of political science, 891–913.

Fiorina, M. P. (1978). Economic retrospective voting in American national elections: A micro-analysis. American Journal of Political Science, 426–443.

Hacker, J. S., Rehm, P., and Schlesinger, M. (2013). The insecure American: Economic experiences, financial worries, and policy attitudes. Perspectives on Politics, 11(1), 23–49.

Healy, A., and Malhotra, N. (2010). Random events, economic losses, and retrospective voting: Implications for democratic competence. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 5(2), 193–208.

Hobolt, S. B., and De Vries, C. E. (2016a). Public support for European integration. Annual Review of Political Science, 19, 413–432.

Hobolt, S. B., and De Vries, C. E. (2016b). Turning against the Union? The impact of the crisis on the Eurosceptic vote in the 2014 European Parliament elections. Electoral Studies, 44, 504–514.

Hobolt, S. B., and Tilley, J. (2014). Blaming europe? Responsibility without accountability in the European Union. Oxford University Press.

Hobolt, S. B., Spoon, J. J., and Tilley, J. (2009). A vote against Europe? Explaining defection at the 1999 and 2004 European Parliament elections. British journal of political science, 39(1), 93–115.

Kinder, D. R., and Kiewiet, D. R. (1979). Economic discontent and political behavior: The role of personal grievances and collective economic judgments in congressional voting. American Journal of Political Science, 495–527.

Kramer, G. H. (1971). Short-term fluctuations in US voting behavior, 1896–1964. American political science review, 65(1), 131–143.

Lipset, S. M. (1960). Political Man. Anchor Books, Garden City, New York.

Margalit, Y. (2013). Explaining social policy preferences: Evidence from the Great Recession. American Political Science Review, 107(1), 80–103.

Marquart, F., Goldberg, A. C., van Elsas, E. J., Brosius, A., & de Vreese, C. H. (2018). Knowing is not loving: Media effects on knowledge about and attitudes toward the EU. Journal of European Integration. DOI: 10.1080/07036337.2018.1546302

Norris, P., and Inglehart, R. (2018). Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge University Press.

Pirro, A. L., Taggart, P., and Van Kessel, S. (2018). The populist politics of Euroscepticism in times of crisis: Comparative conclusions. Politics, 38(3), 378–390.

Polk, J., and Rovny, J. (2017). Anti-elite/establishment rhetoric and party positioning on European Integration. Chinese Political Science Review, 2(3), 356–371.

Rehm, P. (2011). Social Policy by Popular Demand. World Politics 63(2): 271–299.

Reif, K., and Schmitt, H. (1980). Nine second‐order national elections–a conceptual framework for the analysis of European Election results. European journal of political research, 8(1), 3–44.

Schnattschneider, E. E. (1960). The semi-sovereign people. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Taggart, P., and Szczerbiak, A. (2004). Contemporary Euroscepticism in the party systems of the European Union candidate states of Central and Eastern Europe. European Journal of Political Research, 43(1), 1–27.

Treib, O. (2014). The voter says no, but nobody listens: causes and consequences of the Eurosceptic vote in the 2014 European elections. Journal of European Public Policy, 21(10), 1541–1554.

Van der Brug, W., and Van der Eijk, C. (2007). European elections and domestic politics: Lessons from the past and scenarios for the future. University of Notre Dame Press.

Franklin, M. N., and Van der Eijk, C. (1996). Choosing Europe? The European electorate and national politics in the face of union. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Method

This report presents an overview of a study conducted by Dalia Research in December 2018 on public opinion across 28 EU Member States. The sample of n=11,735 was drawn across all 28 EU Member States, taking into account current population distributions with regard to age (14-65 years), gender and region/country. In order to obtain census representative results, the data were weighted based upon the most recent Eurostat statistics. The target weighting variables were age, gender, level of education (as defined by ISCED (2011) levels 0-2, 3-4, and 5-8), and degree of urbanization (rural and urban). An iterative algorithm was used to identify the optimal combination of weighting variables based on sample composition within each country. An estimation of the overall design effect based on the distribution of weights was calculated at 1.46 at the global level. Calculated for a sample of this size and considering the design-effect, the margin of error would be +/-1.1 % at a confidence level of 95 %.