When to the sessions of sweet silent thought

I summon up remembrance of things past,

I sigh the lack of many a thing I sought,

And with old woes new wail my dear time’s waste.

William Shakespeare, Sonnet 30

Executive Summary

Nostalgia is a powerful political tool. References to a better past are skillfully employed by populist political entrepreneurs to fuel dissatisfaction with present-day politics and anxiety about the future. But we know little about who is most receptive to those messages evoking a halcyon, bygone era. What share of the European public is nostalgic about the past, and what kind of political solutions does it prefer? In this report, we provide an in-depth look into Europeans’ feelings of nostalgia and how they affect views about politics today. Our empirical evidence is based on a representative survey conducted in July 2018 in which 10,885 EU citizens participated.

Our findings show that a majority of the European public can be classified as nostalgic. Although younger segments of the population are slightly less nostalgic than their older counterparts, a majority of those over 35 years of age think that the world used to be a better place. The younger generations are least nostalgic in Poland, most so in Italy. Our evidence suggests that those most likely to harbour feelings of nostalgia are men, the unemployed, those who feel most economically anxious, and those who feel that they belong to the working class.

Psychological research shows that feelings of nostalgia are often triggered by negative moods, anxiety, or insecurity. Nostalgia allows for a retreat into a state of order in which life is more predicable and thus serves as a internal stabilizing-mechanism. What is described by psychologists as a psychological resource serves in the political realm as an instrument for agitation. Which politics attract those individuals who feel nostalgia, and what political priorities do such persons have? On average, those who are nostalgic place themselves somewhat more on the right of the political spectrum, while those who do not feel nostalgic consider themselves more to the left. In terms of political priorities, we find that feelings of nostalgia coincide with an increased concern about migration and terrorism. Overall, the policy preferences of those who feel nostalgic differ most strongly from those who do not feel nostalgic when it comes to migration and immigration. Nostalgic types seem to be more fearful of immigrants and the consequences of migration.

Here are some of the key findings in our report:

- A majority of the European public can be classified as nostalgic. 67 percent think that the world used to be a better place.

- Feelings of nostalgia are most pronounced among Italian respondents and least among Polish respondents. 77 percent of Italians think that the world used to be a better place, while 59 percent of Poles think the same.

- More or less equal shares of French, German, and Spanish respondents harbour feelings of nostalgia. 65 percent of the French, 61 percent of Germans, and 64 percent of Spaniards think that the world used to be better.

- Nostalgia is least pronounced among younger respondents, those below 35 years of age.

- Men are more likely to be nostalgic than women, 53 versus 47 percent respectively.

- The majority of those (53 percent) who feel nostalgic place themselves on the right of the political spectrum, while those who do not feel nostalgia (58 percent) place themselves more on the left.

- 78 percent of those who feel nostalgic think that recent immigrants do not want to fit into society, while 63 percent of those who do not feel nostalgic think the same.

- 53 percent of those who feel nostalgic think that immigrants take away the jobs of natives, while only 30 percent of those who do not feel nostalgic think the same.

- Those who feel nostalgic do not differ much from their non-nostalgic counterparts when it comes to their views on Europe -- with one exception. While a large majority of those who are not nostalgic want to remain in the EU (82 percent), a lesser share of those who feel nostalgic do (67 percent).

- Fighting terrorism is the biggest priority for those who feel nostalgic (60 percent), followed by managing migration (51 percent). Only 47 percent of those who are not nostalgic think that terrorism should be the top political priority in the future, followed by 43 percent who say that migration should be.

Introduction

In our previous reports, Fear Not Values: Public Opinion and the Populist Vote in Europe and Globalization and the EU: Threat or Opportunity?, we demonstrated that many Europeans are worried about the future. As a result of globalization and other sweeping processes of societal change, significant parts of the European public today express a considerable degree of social, economic, and political insecurity. Moreover, our previous reports suggest that these anxieties coincide with high levels of distrust toward mainstream political elites and political institutions, and strong support for populist movements and parties on the far right and far left.

In this report, we explore how these heightened levels of anxiety and fear about the future relate to Europeans’ views about the past. Specifically, we examine feelings of nostalgia. As do prominent sociologists and psychologists, we define nostalgia as the degree to which people feel that the past was better than the present, a sense of loss for times bygone (e.g. Davis 1979, Batcho 1995, Sedikidis et al. 2008, Duyvendank 2011). The scholarship suggests that feelings of nostalgia are commonly triggered in response to increased anxiety and fear fuelled by processes of rapid personal or societal change (Davis 1979, Sedikidis et al. 2008).

Nostalgia is a political tool (Duyvendank 2011). Nostalgic rhetoric has been skilfully employed by populist political entrepreneurs on the left and right to fuel dissatisfaction with the political system and distrust of mainstream political elites at the national and European level (Gaston and Hilhorst 2018). These political entrepreneurs paint pictures of a supposedly better past in which life was more pleasant, untarnished, and predictable; with these images they stir up dissatisfaction with the present and anxiety about future. The far right, in particular, in many European countries has been able to successfully craft an anti-establishment discourse through a rhetoric highlighting “the decline of a golden age” and proposing divisive solutions, mostly based on in-group favouritism and ethnocentrism, to combat these “alleged processes of decay” (Elgenius and Rydgren 2018: 1). Nostalgia has become a powerful political tool to glorify the past, to enable politicians to cull support for regaining that perceived to have been lost, and to reaffirm values and identities that are being challenged by the rapid pace of societal change.

While we know that political entrepreneurs, especially those on the far right and far left, have skilfully fuelled and exploited feelings of nostalgia in order to gain prominence in the public debate and expand their electoral base, we know much less about who is receptive to these messages. Also, we do not know where those who feel nostalgic place themselves on the political spectrum, and what kind of policy priorities and positions they prefer. In this report, we provide an in-depth look into people’s feelings of nostalgia and how they affect political views by addressing three main questions:

- Who is nostalgic?

- Where do people who feel nostalgic place themselves on a left-right political spectrum?

- What policies do people who feel nostalgic support?

This report answers these questions by presenting evidence based on a survey conducted in July 2018 in which we interviewed over 10,000 EU citizens. We present two sets of evidence. One set is based on a sample capturing public opinion in the EU28, and the other completes the picture by focusing more in-depth on respondents from the five largest member states in terms of population: France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain.

The report is organized into five parts. First, we provide a short introduction to the concept of nostalgia and introduce our measurement of it. Second, we examine the degree to which the European public displays feelings of nostalgia and which socio-demographic profile characterizes them. Third, we explore the ideological left-right profile of those interviewed about nostalgia. Fourth, we contrast the policy positions and priorities of those who feel nostalgic with those who do not. Finally, we conclude by highlighting the most fruitful political responses to increasing feelings of nostalgia and the nostalgic political frames employed by populist and far-right and far-left political entrepreneurs.

Feelings of Nostalgia: A Short Overview

In Focus

The word nostalgia stems from two Greek roots: nostos meaning "return home" and algia "longing." While nostalgia features prominently in the arts and literature, social scientists have paid far less attention to the concept. The term was initially coined by a Swiss physician, Johannes Hofer (1669/1752), who used it in reference to adverse psychological symptoms displayed by Swiss mercenaries who spend considerable time abroad. More contemporary thinking, mostly stemming from psychology and sociology, perceives nostalgia as either a personal sentiment or worldview relating to the past (Davis 1979, Batcho 1995, Sedikidis et al. 2008). While psychologists view feelings of nostalgia primarily in reference to personal experiences, such as a birth, education level, or other personal milestones, (Batcho 1995, Sedikidis et al. 2008), sociologists define it in a much broader sense and relate it to more general views about the state of the world (Davis 1979, Duyvendak 2011). For the purpose of this report, we follow the latter tradition and define nostalgia as a feeling that the world used to be a better place, a sense that something good about the past has been lost.

Nostalgia develops in comparison to a benchmark, a reference point in the past (for a discussion of the importance of benchmarks for European public opinion, see De Vries 2018). Because of the fact that these benchmarks are based on a recollection of past times, they will most likely be the result of processes of selective memory and represent more of an idealized past rather than actual depiction. Nostalgia may represent feelings of longing for a past that never existed, a past that is largely constructed. As such, nostalgia may tell us more about present moods than past realties (Nisbet 1972).

Feelings of nostalgia are often triggered by negative moods, anxiety or insecurity about the present accompanying periods of considerable societal change and upheaval. In previous reports, we have shown that globalization has triggered such fears (De Vries and Hoffmann 2016). Globalization, as a process of large-scale social change, is perceived by many to create tensions with current and past customs and traditions. As a result, it can be perceived as threatening the status quo and current way of life. This may in turn trigger feelings of chaos, anxiety, and insecurity.

Nostalgia can act as a powerful means to distract from such anxieties and perceived threats (Sedikidis et al. 2008). It allows for a retreat into a state of order in which life is more predictable. Feelings of nostalgia often have a conservative bent. They may attract people to distinctively conservative political worldviews that stress the preservation of traditional values and previous practices and customs (Davis 1979, Smeekes et al. 2015). These conservative worldviews, with an emphasis on safeguarding tradition, can offer distressed individuals a coping mechanism to better deal with their anxiety and fears. Nostalgia can thus provide a powerful substitute source of control that helps anxious and fearful individuals to permeate their worlds with order and predictability, and create an elevated sense of self-worth or personal control (Kay et al. 2008, Sedikidis et al. 2008, Fritsche et al. 2017).

In political discourse, the term nostalgia is often employed in reference to a golden age, as a return, at least in spirit, to a previous more preferable period in a nation’s history (Smith 2009, Mazur 2015). The development of nostalgic political rhetoric can subsequently contribute to a narrative of decline and crisis, of continuity against change (Elgenius 2011, 2015). Nostalgic political rhetoric is employed by both left-wing and right-wing political forces, usually on the fringes of the political spectrum, and at the expensive centrist political forces (for an overview see Gaston and Hilhorst 2018). While providing a clearly different narrative about the past, political entrepreneurs on the far left and far right develop a rhetoric of decline that questions the motives of current political elites. It may even sow doubts about the representative system as a whole with the defence of a desire for ‘genuine political involvement’ and by ‘the people’.

On the left, one can currently think of the British Labour Party under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn, the German Left Party under Sarah Wagenknecht, and Senator Bernie Sanders in the United States for example. Far-right parties have perhaps been most successful at fuelling and exploiting feelings of nostalgia (Betz and Johnson 2004, Rydgren 2018, Steenvoorden and Harteveld 2018). This might be because these parties are able to effectively frame their anti-elitist discourse of current malaise in terms of the decline of a national golden age (Elgenius and Rydgren 2018, Steenvoorden and Harteveld 2018). Referring to a sense of better past or even national grandeur acts as a suitable political device in the present. Think of Donald Trump’s campaign slogan of “Making America Great Again”, or the slogan of many Brexiters: “Taking Our Country Back”. While few right-wing political entrepreneurs may actually wish to return to the periods they purport to idealize (Rydgren 2018), they can reap electoral gains by constructing a political project based on the past and claiming that the present one is doomed to fail.

After having elaborated some of the social and political roots of the concept of nostalgia, the question now is how we can best empirically measure it. While no established tradition exists, most empirical approaches focus on people’s perceptions of the past (Batcho 1995). While these perceptions could empirically be linked to general feelings of societal discontent, insecurity, unease, or anxiety (Steenvoorden 2015), it follows from our discussion above that we ought to capture their conceptual content separately. This is because many psychologists and sociologists view nostalgia as a coping mechanism, as a reaction to heightened levels of insecurity or anxiety. Recent studies have operationalized nostalgia by asking respondents if they felt that life was better when they were growing up; whether their community had improved or declined over the course of their lifetime or whether things in their country where better in the past (Gaston and Hilhorst 2018, Fieldhouse et al. 2016). We base our empirical measure of nostalgia on this previous work, and aim to evaluate people’s general perceptions of the past. In order to determine people’s degree of nostalgia, we rely on the following survey question: To what extent do you agree with the following statement? “The world used to be a much better place.” The answer categories were “completely disagree”, “disagree”, “agree”, and “completely agree”. We classify respondents as nostalgic when they either respond to “agree” or “completely agree” with the statement, and those as non-nostalgic who either “completely disagree” or “disagree”. In the next section, we explore the share of the European public that can be classified as nostalgic, and contrast its socio-demographic profile to those who are not.

Who Is Nostalgic?

Figure 1 provides an overview of the share of people in the EU28 and the five largest EU member states -- Germany, France, Italy, Poland, Spain -- who can be classified as nostalgic versus those that are not. Interestingly, the results show that a majority of the European public can be classified as nostalgic and agrees with the statement that “the world used to be a better place”. 67 percent of citizens within the EU as a whole think that the world used to be a better place. More or less equal shares of French, German, and Spanish respondents think the same: 65, 61, and 64 percent think that the world used to be better.

In a recent study of popular and party-based nostalgia in Germany, France, and the United Kingdom, political scientists Sophie Gaston and Sasha Hilhorst (2018) also find that feelings of nostalgia are widespread. In our survey, nostalgia is least pronounced among the Polish public: 59 percent of Polish respondents think the world used to a better place. It is most pronounced in Italy, where a staggering 77 percent of Italian respondents think that the world used to be a better place.

Given that feelings of nostalgia are commonly associated with a longing for the past as a means to deal with anxiety and insecurity about the present or future, it might be the case that nostalgia is somewhat more pronounced among older generations. Figure 2 below provides an overview of the share of the European public that displays feelings of nostalgia among five different age groups: 1) 16 to 25; 2) 26-35; 3) 36-45; 4) 46-55; 5) 56-65.[1] The results for the EU28 suggest that those below 35 are indeed the least nostalgic. But we also find very few differences among those between 36 and 65 years of age. This is perhaps not entirely surprising since studies in psychology that investigate generational differences in nostalgia find only small differences based on age (Batcho 1995). The results for the EU28 suggest that a majority of respondents can be classified as nostalgic irrespective their age.

When we look more closely at age patterns in the five countries, we find that the youngest age cohort is least nostalgic in Poland, followed by Germany. Only 35 percent of Polish respondents between 16 and 25 think that the world used to be a better place, while 42 percent of Germans in the same age group think the same. The 16 to 25-year-olds in France and Spain are almost evenly split between feeling nostalgic and not. Nostalgia is most pronounced among the youngest age cohort in Italy. A large majority of the 16 to 25-year-olds in Italy, namely 64 percent, think that the world used to be a better place. Among the older age cohorts in Italy, we find a comparatively high level of nostalgia: 80 percent of the 56 to 65-year-olds in Italy think the world used to be better.

[1] Note that due to our online sampling methodology our survey only includes respondents between 16 and 65 years old.

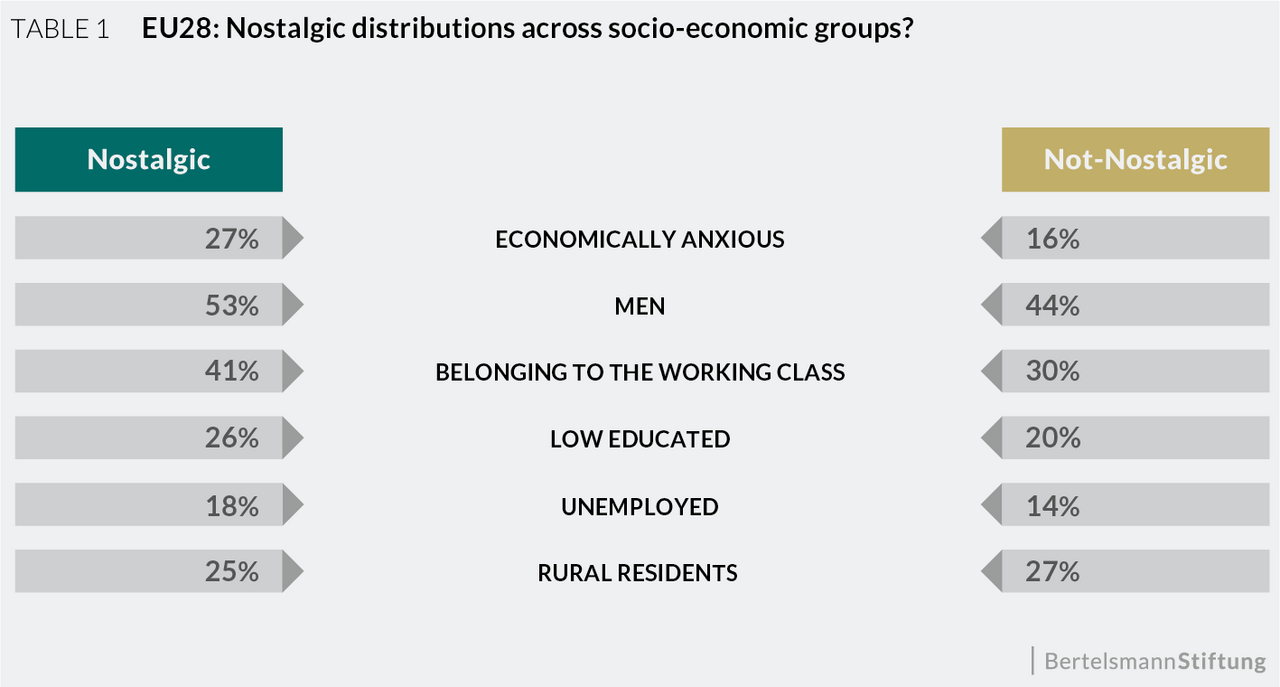

What is the socio-demographic profile of those who feel nostalgic versus those who do not? Table 1 provides this information. Specifically, the figure contrasts the share of men, rural residents, unemployed, low educated, economically anxious or belonging to the working class among those who feel nostalgic versus those who do not in our survey. 27 percent of those who feel nostalgic are also economically anxious versus only 16 percent among those who are not nostalgic. The share of men is much higher among those feeling nostalgic: 53 versus 44 percent among those who do not feel nostalgic. The share of those who identify with the working class is also higher among those who feel nostalgic: 41 versus 30 percent. The share of those with only a high school education (or less) is also more pronounced among the group that feels nostalgic, 26 versus 20 percent respectively. The differences based on rural residency or unemployment are overall much less pronounced. Taken together, this evidence suggests that men, the unemployed, and those who feel working class or economically anxious are especially overrepresented among those in our survey who feel nostalgic. These results support the idea that nostalgia may be an especially potent force among those who have already experienced or fear to experience soon economic hardship or lost social standing (Davis 1979, and more recently Gaston and Hilhorst 2018, Steenvoorden and Harteveld 2018).

Where Do People Who Feel Nostalgic Place Themselves Politically?

Where do those who feel nostalgic place themselves on a left-right ideological spectrum? In our July 2018 survey, we also asked respondents about their ideological views. Specifically, we asked them to place themselves on a spectrum encompassing left, centre left, centre right, and right. Figure 3 below provides an overview of the left-right placements of all respondents in the survey, while Figure 4 contrasts the left-right placements of those who feel nostalgic and those that do not. This allows us to get a sense of the extent to which people who feel nostalgic deviate in terms of their ideological self-placement.

Let us first turn to the results for the EU as a whole. In the EU28, we find that those who are nostalgic place themselves somewhat more on the right of the political spectrum, while those who do not feel nostalgic place themselves somewhat more to the left. Of those who think that the world used to be a better place, 20 percent view themselves as left, 27 percent as centre left, 32 percent as centre right, and 21 percent as right. Of those who do not think that the world used to be a better place, 22 percent view themselves as left, 36 percent as centre left, 27 percent as centre right, and 15 percent as right. When it comes to all respondents, 21 percent view themselves as left, 30 percent as centre left, 30 percent as centre right, and 19 percent as right.

The differences between those who feel nostalgic versus not based on their ideological left-right self-placements are most pronounced among French and German respondents. In France, among those who feel nostalgic 12 percent more view themselves as right wing compared to those who do not feel nostalgic. An even starker pattern emerges from the German results: the share of those who view themselves as right or centre-right is 20 percent higher among those who feel nostalgic than those who do not. The differences in self-placement on an ideological left-right scale are least pronounced among Polish respondents.

What Policies Do People Who Feel Nostalgic Support?

After having established who displays the strongest feelings of nostalgia and where those who feel nostalgic place themselves on a left-right ideological spectrum, we now turn to an examination of policy preferences and priorities. For this, we focus on political attitudes that relate to two sets of policy areas that have been among the most contentious and politically divisive in the European context in recent years, namely immigration and European integration (Kriesi et al. 2008, De Vries 2018). We focus on people’s preferences concerning both of these policy areas, and begin by contrasting attitudes towards immigrates and immigration policy between those who feel nostalgic versus those who do not.

Figure 5 and Figure 6 provide an overview of immigration attitudes. Figure 5 presents the share of those EU Europeans who agree with the following four statements :

- Immigrants take jobs away from natives.

- Recent immigrants don't want to fit into society.

- Immigration is good for the economy.

- Immigrants enrich the cultural life of the nation.

The results suggest that those who think that the world used to be a better place are more likely to hold more negative views about immigration. Among those who feel nostalgic, 53 percent agree with the statement that “immigrants take away jobs from natives” and 78 percent agree with the statement that “recent immigrants don't want to fit into society”. These shares are considerably lower among those who do not feel nostalgic, 30 versus 63 percent respectively. A large majority, over 60 percent of those who do not feel nostalgic agree with the statements that “immigration is good for the economy” and “immigrants enrich the cultural life of the nation”, while only 45 and 50 percent of those who do feel nostalgic agree.

Figure 6 aims to put these views about immigration in the context of views about other groups in society. The results are based on responses to a question asking which of the following six groups of people respondents do not wish to have as their neighbours:

- immigrants;

- gays or lesbians;

- people with a different religion;

- people who speak a different language;

- families with children;

- smokers.

The results reaffirm our previous impression that people who feel nostalgic are more wary of immigrants: 27 percent of them do not wish to have them as neighbours, while only 15 percent of those who do not feel nostalgic are of the same opinion. Among those who feel nostalgic, opposition towards immigrants as neighbours is the most pronounced compared to negative feelings towards any of the other groups. This is not the case among those who do not feel nostalgic. They are most strongly opposed to having smokers as their neighbours. The overall opposition towards immigrants as neighbours within our sample as a whole, is with less than 25 percent, not so high. It is important to keep in mind in this respect that respondents may want to give socially desirable answers to this question in order not to appear prejudiced.

In a second step, we compare and contrast the EU attitudes and policy priorities of those who feel nostalgic versus those who do not. Figure 7 and Figure 8 provide this information. Figure 7 shows the share of respondents who wish their country to remain a member of the EU, wish to see more political and economic integration in Europe, want the EU to play a more active role on the world stage, want more EU involvement in border control, and think that EU citizens should be allowed to work and settle in other EU member states. Interestingly, the differences between those who feel nostalgic versus those who do not are much less pronounced when it comes to people’s EU preferences compared to their attitudes towards immigration or immigrants. The exception to this pattern is the share of those wishing to remain in the EU. The remain share is considerably lower among those who feel nostalgic compared to those who do not feel nostalgic, 67 versus 82 percent respectively.

Finally, Figure 8 provides an overview of what people think the policy priorities of the EU should be in the future. The top policy priority of those who feel nostalgic is the fight against terrorism. 60 percent of those who feel nostalgic think that fighting terrorism should be the most important policy goal that the EU should pursue in the coming years. The second most important policy priority is the management of migration. Interestingly, as in our previous report on globalization fears, feelings of nostalgia coincide with an increased concern about migration and terrorism. For those who do not feel nostalgic, securing peace and protecting citizens’ rights are almost equally important compared to fighting terrorism.

Taken together, the findings in Figures 5 and 6, as well as 7 and 8, suggest that the policy preferences of those who feel nostalgic differ most strongly from those who do not feel nostalgic when it comes to migration and immigration.

Concluding Remarks

In this report we show that large segments of the European public are nostalgic about the past. 67 percent of our respondents say that they think that the world used to be better place compared to today. Although feelings of nostalgia are lower among younger generations (those below 35 years of age), they do not differ much between those 36 and older. Feelings of nostalgia are most pronounced in Italy and least in Poland. Moreover, those who are nostalgic are more likely to view themselves as politically right wing. Interestingly, our results suggest that those who are nostalgic are not necessarily Eurosceptic. What makes those who are nostalgic stand out is their skeptical view of immigration and migration, and their concern about terrorism.

Research from the fields of psychology and sociology suggests that nostalgia can be a coping mechanism to deal with feelings of anxiety or insecurity. Currently, we are going through a period of considerable societal change and upheaval, stemming from x changes technological, political, and economic. Globalization, as a process of large-scale social change, is perceived by many as a threat to societal order and people’s standing, in that order. Nostalgic rhetoric about a societal golden age where everything was better and more predictable can serve as a powerful antidote to heightened levels of anxiety and perceived threats. Such nostalgia favours order over chaos, the known over the unknown, the idealized over the real. It is perhaps no surprise that those who are nostalgic are drawn to the more right-wing and conservative end of the political spectrum where political parties stress the preservation of traditional values rather than societal change.

The paradox of the success of nostalgic rhetoric is that its focus on a past – that is, a selective and constructed version of it – entails a demand for a radical break with the present. Today’s political entrepreneurs who peddle nostalgia call for a shift away from the status quo towards an unknown end. It is an open question, though, if these nostalgic visions can be a basis for effective governing and the political problem solving which requires compromises and planning.

We should not simply discard the success of a rhetoric of nostalgia based on its lack of realism. The main challenge for mainstream parties on the left and right is to deal with the underlying anxieties and fears that make people open for feelings of nostalgia: to ask, who presents the world as unorderly and chaotic, and how might we help people to feel safe and secure? How can political elites formulate and articulate views about the future, even those developed from idealized views of the past, that give people a sense of hope rather than fear. Emotions will remain part of people’s lives and inform their understandings of their societies. The elevation of these emotions, then directed towards present and future political goals articulated in the name of lessening current anxieties, might well assist in the management of political problems rather than furthering any perception of instability. To date many mainstream politicians focus mainly on technocratic solutions, thus ignoring these emotional needs. Nostalgia could be allowed to create a politics which exaggerates insecurities, but it might also be invoked to establish a politics which curtails anxieties and establishes a more secure future. This would require politicians to develop rhetoric that is sensitive to the past, while at the same time hopeful towards the future.

References

Batcho, K. I. (1995). Nostalgia: A Psychological Perspective. Perceptual and motor skills, 80(1), 131-143.

Betz, H.‐G. & Johnson (2004). Against the Current—Stemming the Tide: The Nostalgic Ideology of the Contemporary Radical Populist Right. Journal of Political Ideologies, 9:3, 311-327.

Davis, F. (1979). Yearning for Yesterday: A Sociology of Nostalgia. New York: Free Press.

De Vries, C.E. (2018). Euroscepticism and the Future of European Integation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

De Vries, C. E., & Hoffmann, I. (2016). Fear Not Values: Public Opinion and the Populist Vote in Europe. Bertelsmann Stiftung.

Duyvendak, J. W. (2011). The Politics of Home: Belonging and Nostalgia in Western Europe and the United States, Palgrave, London.

Elgenius, G. (2011). The Politics of Recognition: Symbols, Nation Building and Rival Nationalisms. Nations and Nationalism, 17(2), 396-418.

Elgenius, G. (2015). National Museums as National Symbols: A Survey of strategic Nationbuilding; Nations as Symbolic Regimes. In P. Aronsson and G. Elgenius (eds.), National Museums and Nation-Building in Europe 1750-2010, London: Routledge, pp. 145–166.

Elgenius, G., and Rydgren, J. (2018). Frames of Nostalgia and Belonging: The Resurgence of Ethno-nationalism in Sweden. European Societies, 1-20.

Fieldhouse et al. (2016). Brexit Britain: British Election Study Insights from the Post-EU Referendum Wave of the BES Internet Panel. URL: www.britishelectionstudy.com/bes-resources/brexit-britain-british-election-study-insights-from-the-post-eu-referendum-wave-of-the-bes-internet-panel/ (accessed 14th of August 2018).

Fritsche, I., Moya, M., Bukowski, M., Jugert, P., Lemus, S., Decker, O., Valor-Segura, I. and Navarro-Carrillo, G. (2017). The Great Recession and Group-Based Control: Converting Personal Helplessness into Social Class In-Group Trust and Collective Action. Journal of Social Issues, 73(1), 117-137.

Gaston, S. and Hilhorst, S. (2018). At Home in One’s Past: Nostalgia as a Cultural and Political Force in Britain, France and Germany. Demos.

Hofer, J. (1934). Medical dissertation on nostalgia (C. K. Anspach, Trans.). Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 2, 376–391. (Original work published 1688).

Kay, A. C., Gaucher, D., Napier, J. L., Callan, M. J., and Laurin, K. (2008). God and the Government: Testing a Compensatory Control Mechanism for the Support of External Systems. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(1), 18.

Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S., and Frey, T. (2008). West European Politics in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mazur, L. (2015). Golden Age Mythology and the Nostalgia of Catastrophes in post-Soviet Russia. Canadian Slavonic Papers, 57(3-4): 213-238.

Nisbet, R. (1972). The 1930's: America's Major Nostalgia. The Key Reporter, 38(1), 2-4.

Routledge, C. (2016). Nostaligia. A Psychological Ressource. Essays in Social Psychology. New York: A Psychology Press Book.

Rydgren, J. (2018). The Radical Right: An Introduction. In: J. Rydgren (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–16.

Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., Arndt, J., and Routledge, C. (2008). Nostalgia: Past, Present, and Future. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17(5), pp. 304-307.

Smeekes, A., Verkuyten, M., and Martinovic, B. (2015). Longing for the Country’s Good Old Days: National Nostalgia, Autochthony Beliefs, and Opposition to Muslim Expressive Rights’, British Journal of Social Psychology, 54(3), 561–580.

Smith, A. (2009). Ethno-Symbolism and Nationalism: A Cultural Approach. Abingdon: Routledge.

Steenvoorden, E. H. (2015). A General Discontent Disentangled: A Conceptual and Empirical Framework for Societal Unease. Social Indicators Research, 124(1): 85–110.

Steenvoorden, E., & Harteveld, E. (2018). The appeal of Nostalgia: The Influence of Societal Pessimism on Support for Populist Radical Right Parties’, West European Politics, 41(1): 28-52.

Method

This report presents an overview of a study conducted by Dalia Research in July 2018 on public opinion across 28 EU Member States. The sample of n=10.885 was drawn across all 28 EU Member States, taking into account current population distributions with regard to age (14-65 years), gender and region/country. In order to obtain census representative results, the data were weighted based upon the most recent Eurostat statistics. The target weighting variables were age, gender, level of education (as defined by ISCED (2011) levels 0-2, 3-4, and 5-8), and degree of urbanization (rural and urban). An iterative algorithm was used to identify the optimal combination of weighting variables based on sample composition within each country. An estimation of the overall design effect based on the distribution of weights was calculated at 1.46 at the global level. Calculated for a sample of this size and considering the design-effect, the margin of error would be +/-1.1 % at a confidence level of 95 %.