eupinions audio

NEW! Don’t feel like reading? No worries, we got you. Listen to our new podcast that summarizes all important elements of our most recent study.

Executive Summary

As the new European Commission prepares to take office, it faces a considerable challenge. The Commission must prove itself capable of tackling pressing political issues, such as climate change, slowing economic growth, migration and challenges to the rule of law while exercising caution in balancing the interests of the various political forces that now make up the European Parliament and which influence the member states of the European Council. The Commission also needs to be responsive to citizens’ concerns at a time when expectations about what European politics needs to deliver are running high but public confidence in politicians’ capacity to deliver is running low.

Against this backdrop, it is crucial to understand what Europeans want from the new Commission. What do European citizens think are the most important issues for the Commission to protect? And what do they worry about most when it comes to their personal lives? These are some of the questions we tackle in this report. We present evidence based on a survey conducted in early June 2019 in which we polled more than 12,000 citizens across the EU. We present two sets of evidence; one is based on a sample capturing public opinion in the EU27 (excluding the United Kingdom), and the other that focuses on respondents from six member states: France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland and Spain. We also take a closer look at responses in terms of different age cohorts and party support. In sum, there are five key findings.

- Within the EU27, the respondents stated that the environment is the EU’s key priority for the future (40%). For them, the second most important issue is jobs (34%), followed by social security (23%), citizen rights (21%) and public safety (19%). While the environment is a key priority in France, Germany, the Netherlands and Poland, it is not considered the top priority in Italy and Spain. Within the EU27, young respondents between 16 and 25 years of age also care mainly about the environment (47%) but also about equal opportunities (20%).

- Within the EU27, some 51% of respondents identified rising living costs as the issue that worries them most. Poor health (28%), job insecurity (25%) and crime (21%) also feature high on people’s list of personal worries. While rising living costs is the key concern in the six countries subject to an in-depth examination, French and Polish respondents (61% and 62%) stand out in this regard. Interestingly, German respondents express a particular concern about political radicalism. A comparison of concerns collated by age difference shows that young adults across the EU27 are much more concerned about loneliness than their older counterparts.

- The results suggest that within the EU27, people are quite supportive of the EU. In fact, 54% of the respondents expressed support for a deepening of European political and economic integration, 62% said they would speak positively about the EU in conversations with friends, and 50% express optimism about the future of the EU. There are interesting differences across countries: Italian respondents, for example, express a greater desire for a considerable deepening of European integration but are least likely to speak positively about the EU in conversation with a friend. There are also generational differences to be noted. Whereas the youngest cohort (16-25 year-olds) of respondents express the greatest support regarding EU integration, those aged 46 to 55 are most skeptical about it.

- When asked about the likely future evolution of the EU, 35% of respondents within the EU27 said that more exits like that of the UK are likely, while 31% of respondents expect to see different speeds of integration. Some 20% of respondents stated that they believe things will remain the same, while 9% stated that the EU will not exist in the future, and 5% think that there will be a United States of Europe at some point in the future. France shows the highest percentage (42%) of those who expect to see more attempts to exit the EU, while Spain shows the lowest in this regard (28%). Respondents in Germany are much more likely to think that we will see an EU with different speeds of integration in the future.

- A closer look at the views of respondents who support fringe parties shows that unlike the general public, this cohort is less likely to view the environment as a key priority and prefer an emphasis on jobs. This cohort is also much more skeptical toward the EU than is the broader public. This is particularly true of those who support right-wing parties.

Introduction

On the 16th of July 2019, the European Parliament elected Ursula von der Leyen as the new president of the European Commission, placing in her hands the reins of Europe’s executive institution for the next five years. Von der Leyen, whose candidacy had been marked by controversy because she was not one of the candidates (Spitzenkandidaten) earmarked by political groups within the European Parliament, became the compromise candidate in a period of growing political fault lines among member states. Since neither the political groups in the European Parliament nor the European heads of government in the European Council managed to agree on one of the two top candidates - the Christian Democrat/Conservative Manfred Weber or the Social Democrat Frans Timmermans - the European Council settled on von der Leyen instead, which embodied a middle ground in their eyes.

This in turn led to the break with the Spitzenkandidaten process, according to which the top candidate of the largest political group in the European Parliament would become the natural candidate for the post of President of the European Commission. Many members of the European Parliament took this as a provocation. In the first press conference following her election, von der Leyen expressed her empathy for Parliament’s concerns regarding the break with the procedure while emphasizing the need to work with the different political groups in Parliament in formulating the Commission’s policy program. [1] In the speech ahead of her election, she outlined an ambitious policy agenda for the new Commission that involved everything from formulating a new Green Deal to promoting a more Social Europe to creating a European Defence Union. Her speech was designed to give expression to the spectrum of political voices that now make up the European Parliament. Next to the Conservatives and Social Democrats, the Liberal and Green party groups had become forces to reckon with politically, as well as the euroskeptics. Threading these different viewpoints together into one European vision will be a challenge for the new Commission president.

Indeed, during her coming term of office, von der Leyen will have to find answers to several policy questions, ranging from migrant quotas, to monetary union reform to geopolitical challenges. A great deal of diplomatic effort will be required to reconcile the widely differing positions of member states. Ultimately, the new Commission will have to strike a careful balance in accommodating the different member state interests, varying positions of European parliamentary groups and remain close to the needs and wants of European citizens.

In her speech on the 16th of July, von der Leyen stresses that European citizens “want to see that we [the EU] can deliver and move forward.” [2] This statement echoes a finding that we’ve highlighted in our eupinions reports since publishing our first report What Do the People Want? in September 2015: people want the EU to get things done. While the majority of people support the idea of a united Europe, they are increasingly wary about its current direction. Also, in our report Supportive but Wary: How Europeans feel about the EU 60 year after the Treaty of Romefrom March 2017, our survey results indicate that support for the general policy direction in the EU is much lower than support for membership and further integration. Finally, we collect and publish data four times a year on the attitudes of Europeans regarding national as well as European politics. [3] Over the years, we’ve noticed a consistent pattern that stands out: When it comes to the guiding principles and potential of European politics, Europeans remain supportive. However, when asked about the current state of affairs and what they think the future holds, they become less positive. The message delivered by our survey data and trending data is clear: people want the EU to deliver the policies they care about. They prefer functionality over dysfunctionality and cooperation over conflict.

Against this backdrop, it seems crucial to understand what people want from the new European Commission. What are the main priorities they feel the new European Commission should focus on? And what are the issues that people are worried about when it comes to their own lives? These are the questions we address in this report. We present evidence based on a survey conducted in June 2019 in which we asked over 12,000 citizens across the EU what they think the EU should set as policy priorities and which things worry them most with regards to their own lives. We present two sets of evidence; one is based on a sample capturing public opinion in the EU27 (excluding the United Kingdom), and the other takes a closer look at these issues by focusing more in-depth on respondents from six member states: France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland and Spain.

Our findings suggest that people want the new Commission to focus its efforts on protecting the environment, promoting job growth, ensuring the viability of social security and addressing increasing living costs. Our results also suggest that people are – overall – optimistic about the EU, although there are important discrepancies across countries. Moreover, respondents think that the Commission will face increasingly divisive pressures in the future and will therefore move in the direction of promoting varying speeds of integration. They think that the EU might even face more exits like the one we are currently witnessing with the UK. Importantly, respondents who support populist parties on the left or right differ considerably from average voters in member states when it comes to policy priorities and their views on integration. Overall, these findings suggest that the new Commission faces the difficult challenge of addressing citizens’ concerns while expressing sensitivity for the differences between various party supporters.

Before we dig deeper into our results, we will briefly summarize the policy priorities that Ursula von der Leyen has set out in her speech to the European Parliament ahead of her confirmation. Doing so allows us to contextualize our survey findings and see whether her proposals match the views of those citizens surveyed in advance of her speech.

The priorities of the new Commission president

Ursula von der Leyen was elected as the new president of the European Commission by the European Parliament on the 16th of July 2019 in a close vote garnering her only a paper-thin majority of nine votes above the minimum of 374. [4] She addressed the issue cautiously in her first press conference as president-elect: “A majority is a majority in politics [and] I didn't have a majority when I came two weeks ago. People didn't know me.” [5] Von der Leyen, who served as German defense minister at the time of her election, is the first woman in the history of the EU to be elected to the post of Commission president. Given that her name was not on the list of potential candidates that was circulated in Brussels last May following the European Parliament elections, her appointment proved a surprise to many.

The political context surrounding questions regarding who should lead the European Commission was much more complex in the spring of 2019 than it was during the European Parliament elections in 2014. The most recent elections resulted in heavy losses for the two large middle groups in the European Parliament, the conservative European People’s Party and the European Social Democrats, both of which traditionally served as the pool of potentials from which the Commission president emerged. By May 2019, the European Parliament was fragmented and the composition of the European Council, which officially proposes the candidate for the Commission president, was also prone to conflict with confrontations over the rule of law within the member states being far from resolved. In addition, European heads of state were no longer primarily either Conservatives or Social Democrats, and in countries such as Italy, Poland or the Czech Republic, for example, euroskeptic and populist politicians had taken office as leaders. The resistance found among some of these governments would ultimately destroy the candidacy of the Dutch Spitzenkandidat, Frans Timmermans, thereby making room for von der Leyen.

In addition, the largest group, the European People’s Party, had put forward Manfred Weber as Spitzenkandidat who, due to his lack of experience and his support for Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz party, was soundly rejected by French President Emmanuel Macron. At the same time, Macron could find no support for a candidate from his preferred group of liberals, the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE), which nonetheless won clear gains compared to the 2014 parliamentary election and reformed itself to become Renew Europe following the 2019 election.

Von der Leyen eventually succeeded as the winner within the European political minefield in which ideological and national contradictions have grown increasingly profound. She managed to convince a majority of socialists and liberals in the parliament with promises of reforms and actions to take on climate issues and became the first woman to lead the Commission.

In her speech to the European Parliament on the 16th of July, von der Leyen set out an ambitious policy program for the next European Commission. Advocating for “a European Union that strives for more,” [6] she proposed several policies, including the following nine:

- Introduce a Green Deal for Europe to make Europe the first climate-neutral continent in the world by 2050.

- Complete the Capital Markets Union to further break down barriers for cross-border investments and strengthen small and medium-sized enterprises.

- Reform the Stability and Growth Pact and thereby make use of the flexibility envisioned in the rules.

- Strengthen the European Pillar of Social Rights by introducing a European Unemployment Benefit Reinsurance Scheme, ensuring the Youth Guarantee to fight youth unemployment and creating a Child Guarantee to protect children against poverty and social exclusion.

- Strengthen Gender Equality through full gender equality in the College of Commissioners.

- Strengthen the Rule of Law by promoting a new mechanism designed to fully protect basic freedoms.

- Introduce a New Pact on Migration and Asylum in order to strengthen border control by establishing a European Border and Coast Guard Agency and modernizing asylum rules through a Common European Asylum System.

- Establish a European Defence Union in order to facilitate cooperation on matters of security and defense and that foreign policy decisions are made by a qualified majority of member states.

- Introduce political reforms through a Conference on the Future of Europe in which citizens can have their say, improve the Spitzenkandidat system, and ensure a right of initiative for the European Parliament.

The public's priorities

In order to determine what ordinary European citizens prioritize and whether these priorities match up with these policy proposals, we asked survey respondents which issues they think are the most important issues for the EU to focus on in the years to come. Respondents were asked to select two issues from a list of ten:

- Jobs

- The environment

- Minorities

- Social security

- Citizen rights

- Access to education

- Equal opportunities

- Democracy

- Public safety

- None of the above

Figure 1 provides an overview of the responses given. It is important to note that due to the fact that respondents were asked to select two issues (or none) from the list, the answers in aggregate total 200%. For respondents in the EU as a whole (i.e., the EU27, excluding the United Kingdom), the environment is considered to be the EU’s key priority for the future (40%). Jobs are identified as the second most important issue (34%), followed by social security (23%), citizen rights (21%) and public safety (19%). Interestingly, respondents within the EU do not think that the protection of minority rights should be a key future priority for the EU. This is especially noteworthy in light of the recent attention given to the rule of law issues within the EU and the initiation of the article 7 procedure against Poland. Based on these results, it is fair to assume that the broader public has not yet internalized the importance and gravity of the situation with respect to violations of the rule of law.

Figure 1 also highlights interesting variations across countries in what people think the EU’s priorities regarding the future should be. While the environment is a key priority in France, Germany, the Netherlands and Poland, it is not identified as a top priority in Italy and Spain. In Italy, 60% of respondents think jobs are the top priority for the EU, while only 36% think that environment is key. In Spain, jobs are also identified as the key priority (40%), which is followed by the environment and social security (32% respectively). In France and Poland, jobs and the environment are considered of equal importance, with roughly 40% of respondents in France and 36% in Poland identifying both as top priorities in equal measure. In Germany and the Netherlands, the environment is considered to be the key priority (49% and 35% respectively), followed by social security. Jobs are not considered a key priority among Dutch and German respondents (19% and 17% respectively). Public safety is also a key concern among Dutch (29%) and German respondents (23%).

Are there differences between age cohorts when it comes to identifying future policy priorities for the EU? Figure 2 provides an overview of the priorities expressed by European respondents according to age cohorts and depicts some interesting patterns. For those respondents aged between 16 and 25, the environment in particular is seen as a key priority (47%). By contrast, older respondents think the environment is less of a priority.

Young respondents between 16 and 25 years of age also care more about equal opportunities (20%) than does the average of all respondents (17%). This young cohort is considerably less concerned about social security, with only 14% of 16-to-25 year-old respondents identifying this as a priority, while 23% of all respondents see it as a priority. Older age cohorts are also more likely than younger cohorts to identify jobs as a key priority for the EU to focus on in the future. Respondents who are 36 and older also care much more about social security than do younger cohorts. Some 26% of the 36-to-45 year-olds identify it as a key priority, as do 28% of those aged 46-to-55 and 29% of those aged 56-to-65.

The findings presented in figures 1 and 2 suggest that some of the ideas outlined by von der Leyen in her early July speech to the European Parliament dovetail with the policy priorities of European citizens. This is especially the case regarding her proposals for a Green New Deal, an extension of social rights, and a focus on economic and job growth by completing the Capital Union.

Yet, in order to understand more fully what people want politicians to do in terms of their policy mandate, we also have to focus on what people are pre-occupied with in terms of their own lives. This is relevant because people are often unaware of the political aspects of their “private” concerns. We therefore asked them to identify two issues from a list of nine that they worry about most when it comes to their own lives:

- Job insecurity

- Poor health

- Personal loss

- Rising cost of living

- Crime

- Loneliness

- Political radicalism

- Housing

- None of the above

Figure 3 provides an overview of respondents’ answers. Within the EU27, people are most worried about the rising cost of living; 51% identify this issue to be one of the two things they worry about most. Poor health (28%), job insecurity (25%) and crime (21%) also feature high on the list of personal worries. Less than 10% of respondents in the EU as a whole worry about loneliness or personal loss. As in the case of policy priorities, personal priorities also vary by country. While rising living costs is the key concern in all six countries we studied more in-depth, it is a particular concern for French and Polish respondents. A total of 61% of respondents in France and 62% in Poland state that the rising cost of living is a key issue of concern. In Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain, this share varies between 44% and 49%. In Italy and Spain, job insecurity is a similarly strong focus of concern (46% in Italy, 41% in Spain). Interestingly, for German respondents, political radicalism is something they are deeply worried about in their lives. More than one-fourth (28%) name this as a top concern, compared to 16% in the EU as a whole. This result stands in stark contrast to Italy, where only 9% of those polled worry about political radicalism. 25% of German respondents and 23% of Dutch respondents are also worried about crime, while this registers as a worrying point among French, Italian, Polish and Spanish respondents only between 16% and 18%.

What about differences between age cohorts? Figure 4 provides us with an overview and points to several outliers. Similarities across age cohorts include the fact that the rising cost of living registers as the biggest worry across the sample. However, whereas housing is much more of a concern among the 16-to-25 and 26-to-35-year olds, poor health is a major source of worry for the 56-to-65-year olds. This difference is not surprising given the different challenges people face throughout the course of their life cycle. Worth noting is that loneliness is much more of a concern among the youngest age cohort, the 16-to-25-year olds (15%) than it is among those aged 46 or older (6% to 7%).

Our findings presented in figures 3 and 4 suggest that battling rising living costs and job insecurity will be important for the new European Commission, as citizens across the EU are very worried about these issues.

Addressing the key concerns of citizens as well as what they feel should be policy priorities might require the new Commission to develop further proposals for European cooperation and coordination. Against this backdrop, we now examine what people think about the EU and how they expect it to evolve in the future. Figure 5 provides an overview of what people think of the EU. We focus on three questions in particular:

- Do you agree with the following statement? We need more political and economic integration across Europe.

- Imagine you talk with a friend or colleague about the European Union. Would your conversation be positive or negative?

- Overall, do you feel optimistic or pessimistic about the future of the European Union?

The results suggest that overall, people are quite supportive of the EU. Within the EU as a whole, 54% would support deepening political and economic integration in Europe, 62% would express positive views about the EU to friends, and 50% are optimistic about its future. Additional evidence regarding people’s general attitudes and sentiment towards the European Union can be found in our trend numbers which we collect quarterly. We find quite some variation across countries, however. While Italian and Spanish respondents are most supportive of political and economic integration in Europe (roughly 70%), only 39% of Dutch and 41% of French respondents support more political and economic integration. German and Polish respondents fall more in the middle on this issue.

When it comes to conversations about the EU with friends, we see a different pattern. Italians in this case are much more skeptical of the EU. Only 43% of Italian respondents state that they would speak positively of the EU to friends, which is also true for only 50% of French respondents. Polish and Spanish respondents are more likely to express positive views about the EU in conversation with friends (81% and 72%, respectively).

We also find interesting differences across age cohorts, which are depicted in figure 6. Those aged between 16 and 25 are clearly the strongest in favor of European integration. Some 56% of this group support deepening political and economic integration, 69% state that they would speak in positive terms about the EU, and 52% are optimistic about the future of the EU. The 46-to-55 year-olds are the most critical of the EU. Nonetheless, despite the fact that only 48% of those aged 46 to 55 express optimism about the EU’s future, the majority of respondents in this cohort express positive views regarding the EU. Some 52% voice support for more political and economic integration in Europe, and 60% would speak positively of the EU in conversation with friends.

Now we turn to what respondents think the future of the EU will look like. Respondents were asked to select one of five possible scenarios:

- The EU will no longer exist

- More exits like UK

- EU will remain the same

- Different speeds of integration

- A United States of Europe

Figure 7 provides an overview of which scenarios respondents think are most likely for the EU in the future. Within the EU27, respondents are most likely to think that the EU will experience more exits like that of the UK (35%), followed by 31% of respondents who think there will be different speeds of integration in the future. Some 20% think that things will remain the same, while only 9% think the EU will cease to exist in the future, and 5% think that there will be a United States of Europe.

Figure 7 also points to relevant variations across countries. The percentage of those who expect to see more exits like that of the UK is highest in France (42%) and lowest in Spain (28%). German, Italian, Dutch and Polish respondents lie somewhere in the middle with just over 30% of respondents in these countries anticipating more exits. Polish and Spanish respondents prove much more likely to expect that the EU will remain the same (21% and 33%, respectively) than their German and Dutch counterparts (13% and 15%, respectively). Compared with other countries, respondents in Germany are much more likely to think that an EU with different speeds of integration will develop in the future.

Figure 8 provides the distribution across age cohorts. Interestingly, younger age cohorts are much more likely to expect a growing number of UK-like exits (40% of the 16-to-25 year-olds; 37% of the 26-to-35 year-olds). By contrast, only 33% of those aged 46 to 55 and 31% of those aged 56 to 65 expect more exits. Respondents within the older age cohorts are much more likely to think that there will be different speeds of integration (35% of the 56-to-65 year-olds and 33% of the 46-to-55 year-olds) than the younger age cohorts (28% of the 16-to-25 year- olds).

Overall, the results presented in figures 5 to 8 suggest that European citizens hold generally quite positive views of the EU but, at the same time, think that there is a real chance of more exits being pursued like that of the UK or greater differentiation between member states in terms of integration speed. This suggests that while the new Commission can count on public support for tackling key policy concerns and addressing worries through a joint European approach, citizens nonetheless harbor certain reservations about the EU's capacity to act in concert. This finding resonates with a contradiction we’ve observed in earlier studies: Europeans demonstrate a high willingness to support and contribute to the European project but have relatively low expectations regarding how the project pans out in the medium-to-long term.

Policy priorities of those who support populist parties on the right or left

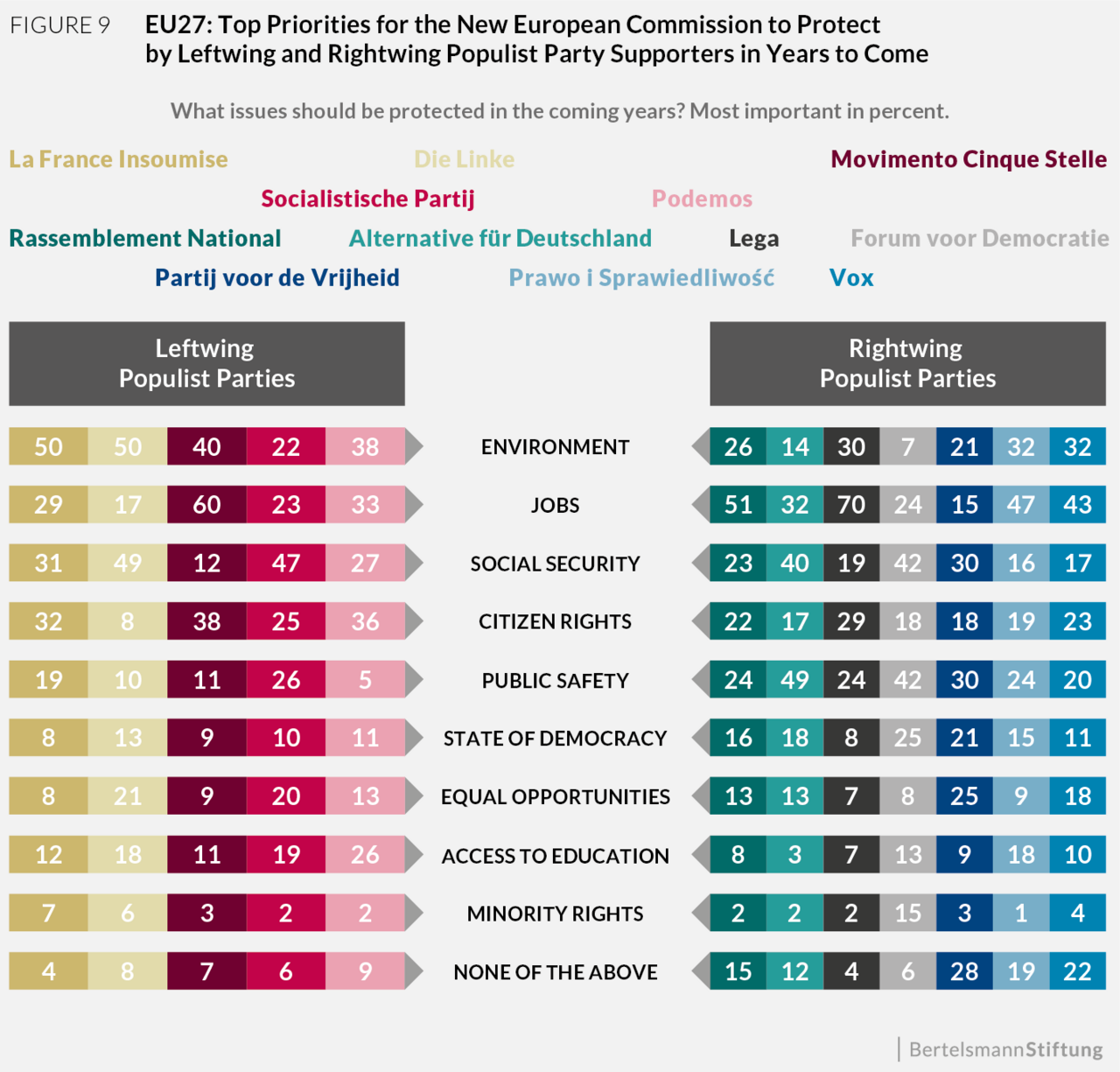

In a final step, we examine how priorities and views regarding the EU differ across supporters of different parties. In this report we choose to focus on the views of those respondents who state that they feel close to populist parties on the left or right of the political spectrum. Having said that, we do provide more detailed breakdowns of the views of all party supporters for the six countries we investigate in more detail. These figures can be found on our accompanying website. Figure 9 provides an overview of what these respondents think the core priorities of the EU should be in the future. It’s worth being reminded here that figure 1 shows that within the EU as a whole, most people think that the environment should be the EU’s key priority in the years to come. In contrast, however, the environment is not identified as a key priority among those who support populist parties to the right. For example, only 7% of those in support of Forum voor Democratie, a right-wing populist party in the Netherlands, think the environment should be made a priority, and only 14% of those in support of the Alternative für Deutschland party see the environment as a key priority. Jobs seem to be the key priority among supporters of the populist right in France Italy, Poland and Spain. Some 51% of supporters of France’s Rassemblement National, 70% of Italy’s Lega, 47% of Poland’s Prawo I Sprawiedliwość (PiS) and 43% of Spain’s Vox placed jobs at the top of their list. Public safety seems to be more important among supporters of the populist right in Germany (49% of Alternative für Deutschland supporters) and the Netherlands (42% of Forum voor Democratie and 30% of Partij voor de Vrijheid supporters).

Supporters of leftist populist parties vary considerably in their desired policy priorities. While supporters of the Movimento 5 Stelle in Italy, a party not easily classified as left or right, think that jobs should be a key priority (60%), supporters of the Dutch Socialistische Partij would prefer prioritizing social security (47%). Supporters of the Die Linke in Germany also care very much about social security (49%) as well as the environment (50%). Supporters of Podemos in Spain view the environment and citizen rights as key priorities (38% and 36% respectively). Those in France who support the La France Insoumise party view the environment as the most important priority (50%).

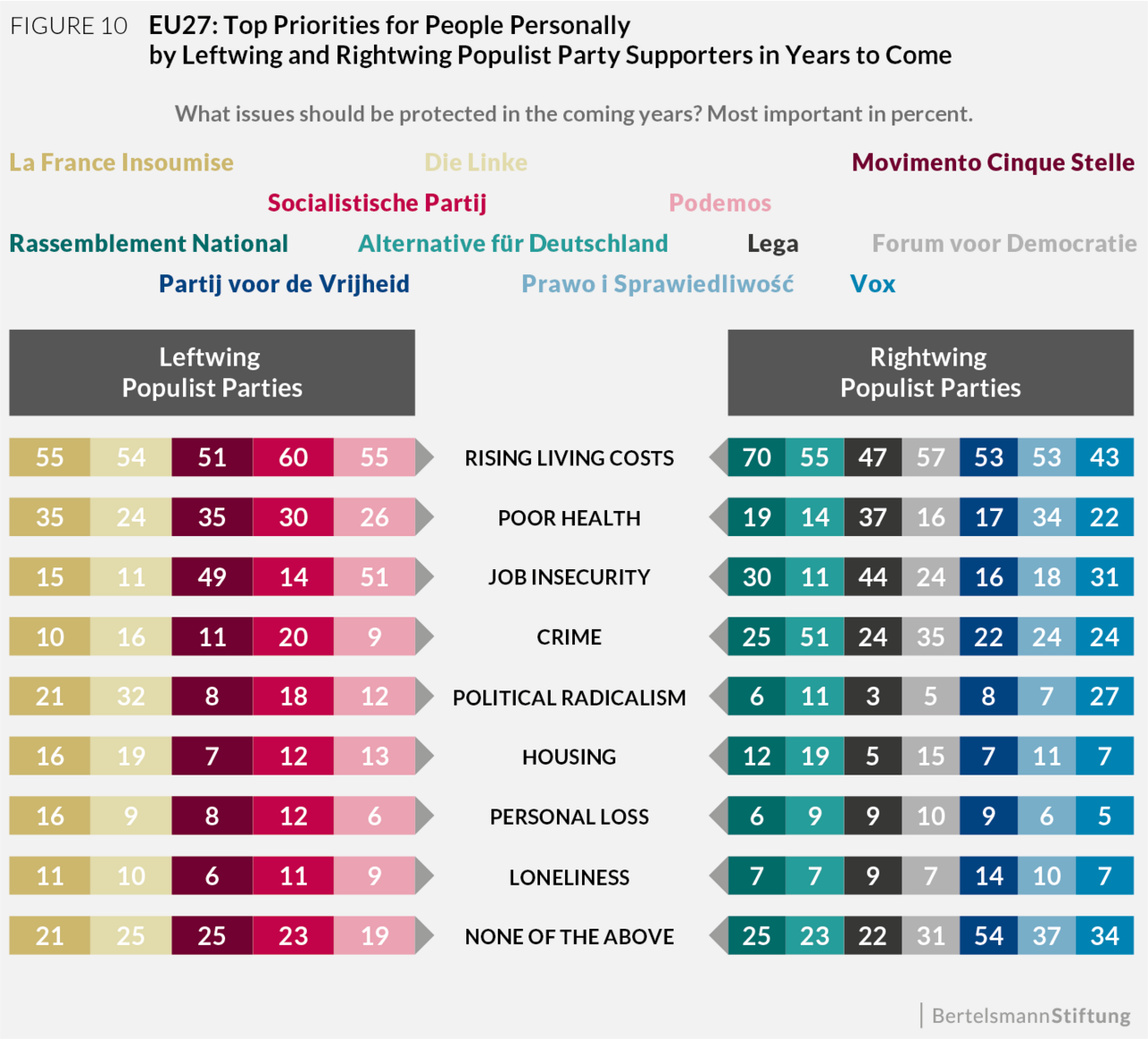

Figure 10 shows the things that supporters of populist parties on the right or left are most worried about when it comes to their own lives. Here we see more uniformity. For party supporters of both the populist left and right, the rising costs of living are the major source of worry in their own lives. This dovetails with our results for European citizens as a whole. For Lega supporters in Italy, job insecurity is also a major source of worry (44%), as it is for those who support the Movimento 5 Stelle (49%) in Italy and Podemos in Spain (51%). Finally, for Alternative für Deutschland supporters, crime is a key source of worry (51%).

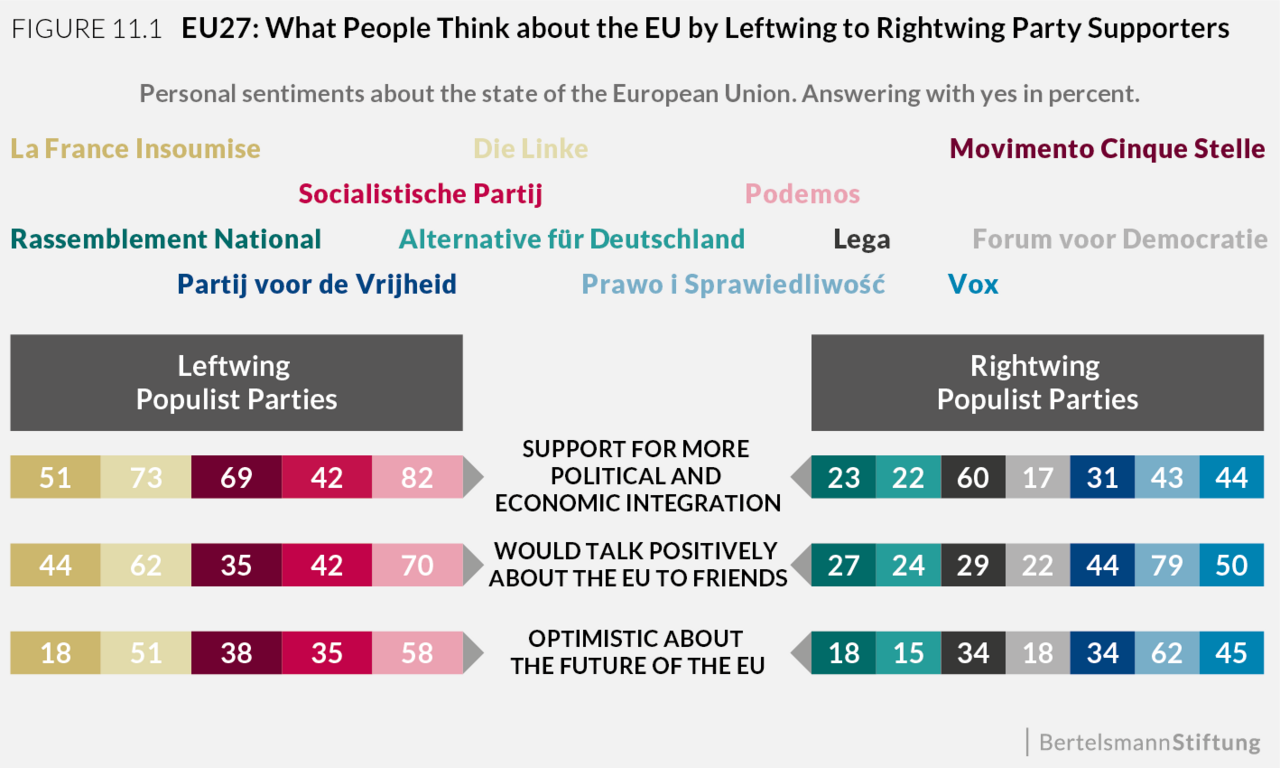

In a last step, we delve deeper into the views regarding the EU that are expressed by supporters of populist parties to the right or left. Figure 11.1 and 11.2 present an overview of the results and underscore several things that stand out. First, most supporters of the populist right express much less positive views of the EU than do the EU27 respondents as a whole or most of those who support the populist left. Alternative für Deutschland supporters in Germany and Forum voor Democratie supporters in the Netherlands express the least positive views regarding the EU. Only 22% of Alternative für Deutschland supporters and only 17% of Forum voor Democratie supporters want more political and economic integration, for example. Interestingly, Lega supporters in Italy are clear supporters of deepening integration (60%) but are, at the same time, not likely to speak positively of the EU in conversation with friends (29%) or express optimism about the EU’s future (34%). Nonetheless, compared to Alternative für Deutschland supporters in Germany and Forum voor Democratie supporters in the Netherlands, Italy’s Lega supporters are more optimistic about the EU.

Second, supporters of populist parties to the left express much more positive views of the EU compared to their counterparts on the right, albeit less so than the general public. Those expressing the most positive views are supporters of Die Linke in Germany (73% support deepening EU integration) and Podemos in Spain (82% express optimism about the future of the EU). The supporters of the Socialistische Partij in the Netherlands report very negative views of the EU that resemble those of supporters of the populist right. A total of 42% of Socialistische Partij supporters are in favor of more political and economic integration in Europe and speak positively of the EU when talking with friends.

Third, supporters of populist parties to the right or left agree more when it comes to their expectations about the future of the EU. Most populist party supporters think that the EU will face more exits like that of the UK, and the share of those who anticipate such exits is higher than that of the general public. Some 48% of Rassemblement National supporters in France and 47% of Alternative für Deutschland supporters think that the EU will face more Brexit-like exits, as do 41% of Movimento 5 Stelle supporters and 40% of Socialistische Partij supporters. In Spain, the largest share of Podemos supporters (35%) think that the EU will remain the same, and the largest share of Die Linke supporters in Germany (44%) think that an EU of different integration speeds will prove most likely.

Overall, the results presented in figures 9, 10, 11.1 and 11.2 suggest that supporters of populist parties differ from the general public in several key aspects. Unlike the general public, they are less likely to view the environment as a key policy priority and would rather prioritize jobs. They also are much more skeptical about the EU compared to the public at large. This suggests that the new Commission will have to find a way to bridge some of the core divisions found among the European public. Perhaps most importantly, the Commission will need to bridge the divide between supporters of mainstream and populist parties, particularly those on the right.

Concluding remarks

Ursula von der Leyen’s pre-election speech, in which she highlighted her personal ties to the European project, attracted considerable press attention. Sharing bits of her family history and personal experience as a child to a father who worked in Brussels and as a mother who speaks with her children about Europe, she gave testimony to the European ideal, not just personally, but also in terms of correspondingly strong policy proposals.

Based on the survey data we have been collecting since 2015, we have good reason to believe that these proposals as well as von der Leyen’s personal attachment and empathy towards the European project, will resonate with a great number of European citizens. However, the key question for most European citizens going forward will be: Can she reach her goals? In light of this question, it’s worth considering the political and institutional environment she faces.

- A newly elected European Parliament that is more heterogeneous and polarized than ever before. The European People’s Party and Social Democrats can no longer exercise their hegemony and must share power with the Liberals and Greens. What’s more, around 25 percent of seats are occupied by populist and nationalist forces, a true testament to novel power relations that are likely going to further complicate the attainment of majorities. Remember that von der Leyen herself secured her confirmation vote by no more than a thin margin of nine votes.

- A European Council that has recently proven it can act as a unified institution when it manages to align the interests within (e.g., Brexit, European top jobs, etc.) but is also challenged by significant internal frictions when it comes to specific principles, worldviews and values (e.g., the rule of law, minority rights, etc.)

- A European public that is – as we have shown in numerous eupinions studies – torn between holding high expectations of what European politics should achieve and a low level of trust in the capacity of the EU to actually deliver.

Ursula von der Leyen has raised the stakes and made promises to a European public that longs for an operational and cooperative EU, but has instead been witness to considerable dysfunctionality and confrontational conflict in recent years. The latter issue begs the question: Even if the new Commission achieves functional cooperation, will it be able to claim and own this success? Given that the European Commission traditionally struggles to construct a narrative, this is a relevant and open question. The Commission grapples with the considerable geographical distance that exists between itself and several member states, the fact that there is no truly European media in place and that it must be both a political actor and the guardian of EU treaties. These conditions have made it difficult for the Commission to reach out to the European public. If the von der Leyen Commission has the ambition to change these conditions, three factors will prove crucial:

- Personal style: From her roles as a top national politician, Ursula von der Leyen is known for her proactive approach to dealing with the media, not shying away from announcing ambitious goals and calling for action. Naturally, this style provokes controversy and invites criticism which von der Leyen has faced frequently throughout her career. All the while, she has been handed difficult portfolios such as the German Federal Ministry of Defence that almost proved fatal to the favorable reputation of her predecessor in this position, Thomas de Maizière. All the more, it is worth stressing that von der Leyen managed to stay in office for five and a half years. Only one of her predecessors held this position for longer. Despite the frequent criticism and attacks, she has not seemed prone to adapt her style. There is no reason to think that she will, as president of the European Commission, act differently.

- Managing style: As the secretary of family affairs, of labor and social issues or of defense, she had to manage her bureaucracy, her portfolio and her performance. In her new position however, she will preside over a large college of commissioners hailing from different backgrounds, each with her/his own set of experiences, capacities and competences. Given the herculean nature of raising the profile of the European Commission and reaching out to the European citizens, the crucial question is whether she will be able to empower other commissioners, thereby allowing them to shine and act as multipliers of the Commission’s agenda. Among those put forth by von der Leyen for the Commission, candidates like Margrethe Verstager and Frans Timmermans have already made a name for themselves in the previous Juncker Commission. Presumably, their strength as political actors and their notoriety will not suffer in the von der Leyen Commission. Other newcomers will be keen to build up a reputation and leave a mark in the Commission's work. Will von der Leyen be able to lead this entire team to success?

- Capacity to work the inter-institutional relationship: When it comes to grabbing the spotlight for the European Commission, the highest hurdle to clear will be improving cooperation with the European Council or, more precisely, the national governments that comprise it. National governments have become accustomed to being able to attract praise for European successes and pass the buck when it comes to failures. Despite growing awareness that this might involve short-term gains at the cost of long-term losses, no national government has thus far proved able to resist playing the blame game. An active and visible Commission will likely clash with various national governments over policy initiatives. This will without doubt complicate the dealings held between the institutions.

The issue of digital taxation comes to mind as one of the potential minefields. As recent as March 2019, the European Council failed to agree on a digital service tax. [7] Some national governments are worried about the impact it would have on companies in their national markets and thus vetoed the plans. Despite this setback, issues that address the digital market, its set-up, regulation and taxation remain crucial for the EU. President-elect von der Leyen raised the point in her election speech: “And I will stand for fair taxes – whether for brick and mortar industries or digital businesses. When the tech giants are making huge profits in Europe, this is fine because we are an open market and we like competition. But if they are making these profits by benefiting from our education system, our skilled workers, our infrastructure and our social security, if this is so, it is not acceptable that they make profits, but they are barely paying any taxes because they play our tax system. If they want to benefit, they have to share the burden.” [8]

This statement certainly resonated with the majority of parliamentarians present in the European Parliament who had voted in favor of the digital service tax in December 2018. [9] But it also clashes with individual national interests represented in the European Council and suggests there will be trouble ahead. For its part, the Council has been struggling to resolve the contradictory interests found among its member states. TechCrunch, the largest publisher for the tech / digital industry, summarizes the situation as follows: “The power of tech giants to influence entire nations is now writ large in EU domestic politics. Europe knows it needs to hammer out an agreement on reforming digital taxation, with rising citizen anger over tax inequalities. The question is how to do it when certain states with low corporate tax rates have been colonized by tech giants which definitely don’t want tax reform to happen.” [10] This is one of many high-stakes issues such as energy policy, migration or eurozone reform that are in need of urgent attention but which are plagued by diverging interests that the Commission will face in its term ahead.

Whatever the challenge or the crisis ahead, the European elections have ushered in a changing of the guard that has altered the European political landscape for good. As they set the tone for the next five years, the new commissioners will have to plan, act capably and be subject to scrutiny.

Glossary

References

[1] European Commission (2019). Press conference by David Sassoli, EP President, and by Ursula von der Leyen, President-elect of the European Commission.

Youtube channel www.youtube.com/watch (accessed: August 2019)

[2] European Commission (2019). Opening Statement in the European Parliament Plenary Session by Ursula von der Leyen, Candidate for President of the European Commission. europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-19-4230_en.htm

[3] eupinions Trends. eupinions.eu/de/trends/

[4] Politico (2019). Ursula von der Leyen’s narrowly won homecoming. www.politico.eu/article/ursula-von-der-leyens-european-commission-president-narrowly-won-homecoming/ (accessed August 2019)

[5] European Commission (2019). Press conference by David Sassoli, EP President, and by Ursula von der Leyen, President-elect of the European Commission.

Youtube Channel www.youtube.com/watch (accessed August 2019)

[6] European Commission (2019). Opening Statement in the European Parliament Plenary Session by Ursula von der Leyen, Candidate for President of the European Commission. europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-19-4230_en.htm (accessed August 2019)

[7] European Council. Council of European Union (2019). Council cannot reach an agreement on EU digital services tax. www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/digital-taxation/ (accessed August 2019)

[8] European Commission (2019). Opening Statement in the European Parliament Plenary Session by Ursula von der Leyen, Candidate for President of the European Commission. ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_19_4230 (accessed August 2019)

[9] European Parliament (2018). Parliament votes on EU-wide tech tax. www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/economy/20181210STO21402/parliament-votes-on-eu-wide-tech-tax (accessed August 2019)

[10] TechCrunch (2019). Where is the EU going on tech and competition policy? techcrunch.com/2019/06/15/where-is-the-eu-going-on-tech-and-competition-policy/ (accessed August 2019)

Method

This report presents an overview of a study conducted by Dalia Research between 2019-06-17 and 2019-06-28 on public opinion across 27 EU Member States, excluding the United Kingdom. The sample of n=12,123 was drawn across all 27 EU Member States, excluding the United Kingdom, taking into account current population distributions with regard to age (16-65 years), gender and region/country. In order to obtain census representative results, the data were weighted based upon the most recent Eurostat statistics. The target weighting variables were age, gender, level of education (as defined by ISCED (2011) levels 0-2, 3-4, and 5-8), and degree of urbanization (rural and urban). An iterative algorithm was used to identify the optimal combination of weighting variables based on sample composition within each country. An estimation of the overall design effect based on the distribution of weights was calculated at 1.42 at the global level. Calculated for a sample of this size and considering the design-effect, the margin of error would be 1.1 % at a confidence level of 95 %.