Executive Summary

In our previous report, “The Optimism Gap", we found that a substantial share of the EU’s population thinks that their own country is not doing well, despite still being hopeful about their own lives. We called this the “optimism gap.” We also discussed what this might mean for the ongoing COVID-19 crisis and European governments’ response to it. People’s tendency to overestimate their own personal resilience in the face of imminent danger could lead to undesirable social outcomes. While European governments have appealed to their citizens’ sense of responsibility by suggesting that individuals should adhere to the rules, thus benefiting everyone, compliance has been far from universal.

In this report, we want to explore the role of empathy in this respect. To what extent does empathy in the sense of being sensitive to the fate of other people help us understand people’s willingness to engage in COVID-19-related health behavior? Does empathy impact people’s views regarding the role that European cooperation should play in the pandemic? We shed light on these questions by presenting evidence based on a survey conducted in June 2020, in which we interviewed nearly 13,000 EU citizens. Our data is representative for the EU as a whole, as well as for the seven member states of Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland and Spain.

In the following report, we summarize our main findings:

- A majority of Europeans overall (55%) display high levels of empathy, but levels of empathy are lower in northern European countries than they are in the southern or east-central regions of Europe. Italian and Spanish respondents display the highest level of empathy, with a respective 65% and 66% of their populations displaying high empathy levels.

- Empathy is structured by left-right political ideology. On average, right-leaning people display lower levels of empathy (50%) compared to left-leaning people (61%). Supporters of right-wing populist parties display the lowest levels of empathy.

- When it comes to COVID-19-related health behavior, those with higher levels of empathy display more cautionary COVID-19-related health behaviors, at least based on self-reports. For example, 61% of those with high levels of empathy say they are willing to follow their government’s COVID-19 rules at all times, while only 45% of those with low levels of empathy state that they do.

- Interestingly, we find little evidence that engagement in COVID-19-related health behavior is highly politicized. For example, supporters of right-wing or left-wing populist parties do not differ substantially from the supporters of mainstream parties when it comes to engagement in COVID-19-related health behavior. Overall, respondents’ willingness to follow COVID-19-related guidelines is quite high.

- Finally, when it comes to views on the EU’s role in the COVID-19 pandemic, the majority of Europeans think that:

- No country is to be blamed for the virus (72%).

- The EU should play a bigger role in future health crises (89%).

- European countries should work more closely together (91%).

- No individual EU member state can deal with the pandemic on its own (53%).

We additionally find several interesting differences across countries, with the Dutch being least favorable toward greater levels of EU involvement and European cooperation. Overall, when it comes to views on European cooperation, those with higher levels of empathy tend to prefer more cooperation and EU involvement, and are less likely to think that their country can act successfully on its own.

Introduction

The devastation caused by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is posing serious challenges to our shared ways of life around the world as deaths mount, economies shut down, jobs evaporate and social isolation becomes the new norm. Governments around the globe are struggling to address the pandemic, and their efforts have varied widely in their effectiveness. In an effort to suppress the virus, governments have imposed extraordinary restrictions on people’s everyday lives, recommending or mandating social distancing and mask-wearing, and often limiting social interactions. While incumbent officeholders experienced a steady increase in popularity during the early phase of the pandemic (Jennings 2020), the last few months have seen more signs of discontent, such as the recent street demonstrations in Germany and France.

While measures such as social distancing, mask-wearing and limitations on social interaction are vital to slow down the spread of COVID-19 in the absence of a vaccine, they are also likely to have significant effects on society’s social fabric. People who are healthy need to change their behavior in order to help the most vulnerable in society. Moreover, although mortality rates are lower for younger generations as compared to older ones, younger people have been the demographic to be most affected by the economic consequences of societal restrictions on movement (Alstadsæter et al. 2020; Montenovo et al. 2020).

The protective measures implemented during the pandemic are ultimately justified by the notion that the behavior of one individual can have devastating effects on the well-being of others. The degree to which an ordinary person cares about others can be seen as one important driver of that individual’s willingness to comply with health-related measures, alongside other factors such as personal economic situation. Empathy – defined as our ability to feel the emotions of others or to identify the mental states of others – has indeed been linked to pro-social behavior in which people act in a way that benefits other people or society at large (Eisenberg and Miller 1987). Empathy may also be important for political leadership during the pandemic. A recent Harvard Business Review piece focusing on the success of female leaders during the pandemic stresses the importance of empathy in leadership (Chamorro-Premuzic and Avivah Wittenberg-Cox 2020). Political commentators, meanwhile, have tried to understand the lackluster response by United States President Donald J. Trump through the prism of an “empathy gap” (Borger 2020). “Empathy has never been considered one of Mr. Trump’s political assets,” writes the chief White House correspondent for The New York Times (Baker 2020).

In this report, we delve deeper into the concept of empathy within the EU27. This is important not only in light of the medical emergency associated with the pandemic, but also in dealing with the economic fallout resulting from lockdowns and social-distancing requirements. The coronavirus outbreak is only the latest stress test for the EU following Brexit, the refugee crisis and the euro zone debt crisis, but it may end up proving the most consequential. Due to the lack of EU policy authority on public health issues, the medical response to the pandemic has been characterized by very substantial national variation. Member-state governments have created a patchwork of measures intended to stop or slow the spread of the virus. When it comes to managing the economic fallout, however, EU institutions have more authority to act. In fact, the Commission and the Council acted swiftly by establishing a recovery fund and agreeing on a new budget framework. Yet, during the negotiations on these issues, it was clear that some member states were less willing than others to extend assistance to peers in less favorable situations (De Vries 2020). For example, several northern European member states, including Denmark and the Netherlands, were reluctant to show solidarity with the highly indebted member states in the south that had been hardest hit by the initial outbreak of the pandemic. In the European context, empathy is thus an important ingredient for success not only in dealing with the pandemic, but also in dealing with the economic fallout across the union.

Against this backdrop, this report addresses three questions:

- How is empathy distributed across EU member states and sociodemographic groups?

- How do levels of empathy relate to COVID-19 related health behavior?

- How does empathy structure people’s views about European cooperation during the COVID-19 pandemic?

This report seeks to answer these questions by presenting evidence based on a survey conducted in June 2020 in which we interviewed just under 13,000 EU citizens. In doing so, we present two sets of data. One set is based on a sample capturing public opinion in the EU27 as a whole, while the other completes the picture with a more in-depth focus on respondents from seven individual member states including Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland and Spain.

The report is organized into six parts. First, we introduce the concept of “empathy,” along with our methodology for measuring it. Second, we examine people’s levels of empathy and how this differs across different EU member states and across different social groups based on gender, age, employment status and other demographic measures. Third, we explore the levels of empathy shown by supporters of different political parties. Fourth, we explore the extent to which empathy structures people’s COVID-19-related health behavior. Fifth, we explore what empathy may mean for people’s views about European cooperation. Finally, we close by reflecting on possible lessons drawn from earlier stages of the pandemic for the importance of empathy in politics.

Exploring Empathy

Empathy is considered to be a powerful force in helping to connect people, enabling one individual to feel invested in the fates of others. The concept of empathy is regarded as important in many different areas of scientific study, from political science (Simas et al. 2020) to behavioral economics (Andreoni 1989), from psychology (Bloom 2017) to psychotherapy (Elliot et al. 2011), and from philosophy (Prinz 2011) to neuroscience (Zaki 2017). While definitions vary, empathy is generally seen as referring to our ability to feel the emotions of others or identify the mental states of others (Eisenberg and Strayer 1987). For example, it can be generated by witnessing another person’s suffering, or by being exposed to the perspective of others (De Waal 2009). Empathy facilitates pro-social behaviors such as cooperation and assistance to others, as it allows us to make sense of and respond appropriately to other people's behavior (Eisenberg and Miller 1987). A general lack of empathy is seen as one of the key characteristics of psychopathy, and is associated with a callous disregard for other people’s well-being (see for example Blair 2013). Empathy is considered distinct from other concepts such as pity. While pity refers to our desire to relieve the suffering of the other person or our ability to show them mercy, empathy can be viewed as our ability to feel the emotions of others or to put ourselves into the shoes of others (Gerdes 2011).

Empathy can be separated into several types, most prominently a cognitive and an emotional type (Hodges and Myers 2007). Cognitive empathy refers to the general ability to recognize and understand another’s mental state. It refers to how well an individual can perceive and understand the emotions of others. Emotional empathy is the ability to share the feelings of others, for example by feeling compassion for another person, or by feeling distress in response to perceiving another’s plight. In this report, we focus on the type that is perhaps closest to the popular conception of the term, emotional empathy. This is also often referred to as empathic concern – that is, people’s tendency to experience other-oriented emotions such as compassion or sympathy for another person who is in distress (Batson et al. 1987).

We measure emotional empathy through a widely validated battery of survey questions often used in the psychology literature (Davis 1983). Note that while some psychologists use as many as 28 items to capture emotional empathy based on an Interpersonal Reactivity Index, in this report we construct an empathy scale based on a smaller subset of questions (see also Simas et al. 2020). Specifically, we construct a scale that measures levels of empathy, from low to high, based on five survey items. We ask people to indicate how well the following five statements describe them:

- “I often have tender concerned feelings for people less fortunate than me.”

- “Sometimes I don’t feel very sorry for other people when they are having problems.”

- “Other people’s misfortunes do not usually disturb me a great deal.”

- “I am often quite touched by things I see happen.”

- “I would describe myself as a soft-hearted person.”

Respondents were able to choose an answer on a five-point scale ranging from “very much like me” (1) to “not at all like me” (5). On the basis of these items, we created an empathy scale for which the highest levels of empathy correspond with stating that statements 1, 4 and 5 were “very much like me,” and that statements 2 and 3 were “not at all like me.” Respondents were classified as displaying “high empathy” when they scored above average on this empathy scale and as “low empathy” when they scored below average on the empathy scale.

Some research has shown that empathy may not always lead to positive outcomes because, under certain conditions, it can lead to partiality in the form of favoring kin and in-group members, thus increasing polarization in society (Simas et al. 2020). However, another line of research has demonstrated positive relationships between empathy, social behavior and cooperation even when it involves personal costs (e.g., Batson et al. 1987). In line with this research, we expect higher levels of empathy to increase people’s compliance with COVID-19 health measures (see also Pfattheicher et al. 2020). Moreover, we would expect respondents with higher levels of empathy to be in favor of more support for European cooperation. In the following sections, we examine the relationship between empathy, compliance with COVID-19-related protective behaviors and support for more cooperation in Europe in the context of the pandemic. Before we do so, however, we explore the levels of empathy observed across the EU27 and in different sociodemographic groups.

Empathy in the EU27

We now turn to the empirical examination of levels of empathy within the EU27 as a whole, in seven individual European countries (Belgium, Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland and Spain) on a more in-depth basis, and across sociodemographic groups. Figure 1 displays the degree to which respondents within our June 2020 eupinions survey display high and low levels of empathy. Within the EU27, a majority of respondents (55%) display high levels of empathy while 45% of respondents display lower levels. Figure 1 also shows that interesting variation exists across countries. Empathy levels are highest among Italian and Spanish respondents, with a respective 65% and 66% of citizens displaying high levels of empathy, and lowest in the Netherlands, where a majority of respondents (55%) display low levels of empathy. In Belgium and Germany, we find a quite even split between low and high levels of empathy, each with a respective 51% and 49%. In France and Poland, more respondents display higher levels of empathy (respectively 61% and 54%) than not, but empathy levels are lower than those observed in Italian and Spanish respondents.

In Figure 2, we explore the relationship between empathy levels and self-reported political ideologies. Here, respondents are split in four groups, left-leaning, center-left-leaning, center-right-leaning and right-leaning. Figure 2 suggests that empathy levels are higher among left-leaning respondents. While right-leaning respondents show an even split between low and high levels of empathy, only a slight majority of center-right-leaning respondents (53%) display high levels of empathy. A clear majority of center-left and left-leaning respondents can be classified in the high-empathy category, with respective high-empathy shares of 57% and 61%.

In moving to the differences between sociodemographic groups, as depicted in Figure 3, it is noteworthy that empathy is more pronounced among women, those over the age of 56, the unemployed, the retired and those who identify as working class. Empathy is least pronounced among male respondents, among whom more than half or 54% display low levels of empathy. Among respondents between 16 and 25 years of age, empathy is evenly split, with 51% displaying high levels of empathy, and 49% displaying lower levels of empathy.

Empathy shown by party supporters

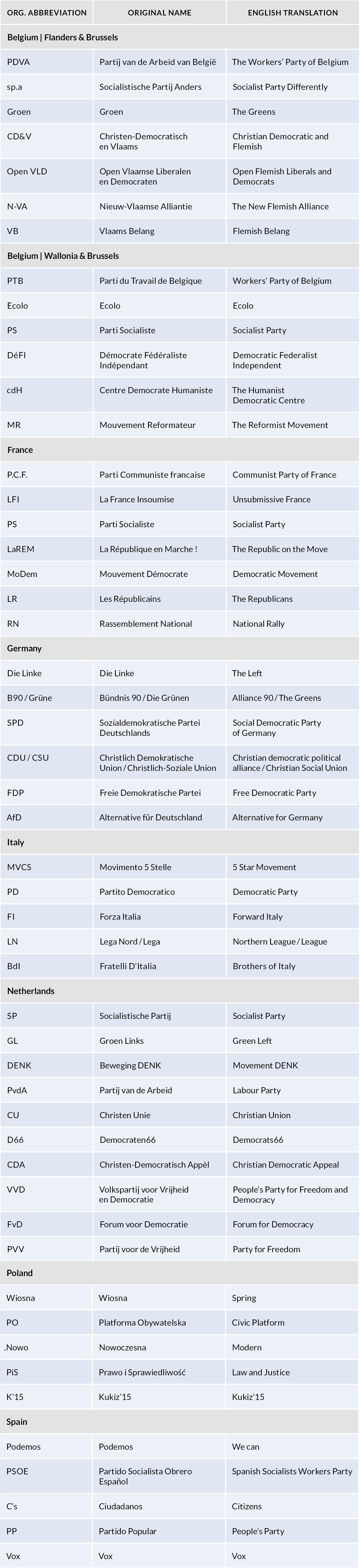

In a next step, we explore empathy levels expressed by supporters of various parties in the seven countries for which we have more in-depth data, namely Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland and Spain. Figures 4 and 5 show levels of empathy among supporters of various parties in Belgium’s Flanders and Wallonia regions. In Flanders, levels of empathy are lowest among supporters of the right-wing populist party, Vlaams Belang. Only 37% of Vlaams Belang supporters display high levels of empathy. Empathy is most pronounced among the supporters of the center-right Christen-Democratisch en Vlaams, with 56% displaying high levels of empathy. In Wallonia, levels of empathy among supporters of specific political parties are on average slightly higher than those of party supporters in Flanders. While empathy levels are highest among supporters of the left-wing Parti du Travail de Belgique, with 67% showing high empathy levels, they are lowest among supporters of the socially liberal regionalist party Démocrate Fédéraliste Indépendant, among whom only 29% display high levels of empathy.

Figure 6 displays empathy levels among party supporters in France. While we know from Figure 1 that, on average, French respondents display relatively high levels of empathy (with a 61% high-empathy share), empathy levels are even greater among supporters of the left-wing Parti Communiste. Indeed, a full 75% of Parti Communiste supporters display high levels of empathy. As was the case for supporters of the right-wing populist Vlaams Belang party in Flanders, the lowest level of empathy can be found among supporters of France’s right-wing populist party, the Rassemblent National. However, empathy levels here are evenly split among Rassemblent National supporters, with 50% displaying low levels, and the other 50% displaying high levels of empathy.

In Germany as a whole, respondents are on average evenly split between low and high empathy. Figure 7 depicts the levels of empathy shown by different party supporters in that country. As in Flanders and France, empathy levels in Germany are lowest among supporters of the right-wing populist Alternative für Deutschland party. Only 36% of this party’s supporters display high levels of empathy. Empathy levels are highest among supporters of the Greens, also known as Bündnis 90/Die Grünen, 56% of whom display high levels of empathy, with 44% displaying lower levels.

Italian respondents as a whole are second only to those in Spain with regard to displaying the highest average levels of empathy within our seven in-depth countries. Figure 8 indicates that Italian respondents who support left-wing parties, specifically the left-wing populist MoVimento Cinque Stelle and the center-left Partito Democratico, display the highest levels of empathy, with respective high-empathy shares of 71% and 70%. The lowest empathy levels can be found among supporters of the right-wing populist Lega party, although a majority of Lega supporters (57%) still display high levels of empathy.

In sharp contrast to Italian respondents, Dutch respondents on average display the lowest levels of empathy among our group of seven countries. Figure 9 shows the levels of empathy among party supporters in the Netherlands. Supporters of the protestant Christian party Christen Unie display the most empathy, with 68% showing high levels, while supporters of the the right-wing populist party Forum voor Democratie display the lowest levels of empathy, with just 33% of the members of the party showing high empathy levels. Thus, the pattern of right-wing populist party supporters displaying the lowest levels of empathy among all party supporters – as seen in Flanders, France and Germany – is again reinforced in the Dutch setting.

Figure 10 displays the levels of empathy among supporters of Polish political parties. Supporters of the right-wing governing party, Prawo I Sprawiedliwość (PiS), display comparatively high levels of empathy, with 59% of supporters showing high empathy levels, a level similar to supporters of the social-liberal Wiosna and the center-right Platforma Obywatelska (with respective high-empathy shares of 59% and 60%). Supporters of Kukiz’15, the political movement led by punk-rock musician turned politician Paweł Kukiz, display the lowest level of empathy, with the high-empathy share totaling just 37%.

Finally, Figure 11 shows the empathy levels displayed by political-party supporters in Spain. On average, Spanish respondents display very high levels of empathy. Figure 11 indicates that empathy levels are highest among supporters of the country’s left-wing parties, the left-wing populist Podemos and Partido Socialista Obrero Español, with both showing a high-empathy share of 70%. Empathy levels are lowest among supporters of the right-wing populist Vox party, though a majority of Vox supporters (53%) in fact do display high empathy levels. Overall, our party-supporter data suggests that supporters of right-wing populist parties tend to be less empathic than supporters of other parties.

Empathy and COVID-19-related health behavior

Research suggests that there is a positive relationship between empathy, cooperation and pro-social behavior – that is, behavior that benefits others and society at large (see for example Batson et al. 1987). Against this backdrop, we could expect that those who display high levels of empathy might be more likely to engage in cautionary COVID-19-related health behavior. In this section, we will compare COVID-19-related health behaviors among respondents with low and high levels of empathy. This is not to say that empathy levels perfectly explain why people do or do not comply with health regulations; indeed, there may be many factors contributing to such behavior, such as differing levels of education or economic resources. All we wish to explore here is whether there are significant differences between those who display low and high empathy when it comes to COVID-19-related health behavior.

In our June 2020 survey, we asked respondents a battery of questions about their COVID-19-related health behavior, with the answers based on self-reports. Figure 12 provides an overview of the number of people respondents are reporting to have met in person the previous day (“yesterday”) who lived outside their own household. Most respondents stated that they had met between one and four people, with respondents’ empathy levels playing very little role in these differences.

Figure 13 provides an overview of the number of people on the previous day (“yesterday”) that respondents have had close contact, shaken hands, hugged, kissed etc., who lived outside their own household. Most respondents (66%) stated that they had had no close contact with people living outside their own household. Here we find that people who display high levels of empathy were 5% more likely than those displaying low levels of empathy to report that they had had no close contacts, with a respective 68% and 63% reporting no such contact.

Figure 14 provides an overview of how much time people had spent on the previous day (“yesterday”) in places in which five or more people had been present. Most respondents (44%) stated that they had not spent any time in places with five or more people on the day in question. People displaying high levels of empathy were 5% more likely than those displaying low levels of empathy to report that they had spent no time in places with five or more people, with respective shares of 46% and 41%.

Figure 15 shows the share of people who reported that they wash or sanitize their hands after being in public places. The majority of respondents (65%) stated that they always washed their hands, but there is a quite substantial gap (15%) between the responses of those with high and low levels of empathy. Overall, 71% of respondents with high levels of empathy reported that they always washed their hands, while only 56% of those with low levels of empathy said the same.

A similar pattern emerges as we explore respondents’ willingness to cover their mouth or nose when sneezing (see Figure 16). In this case, 71% of all respondents stated that they always cover their mouth or nose when sneezing. However, 76% of those with high levels of empathy stated that they did so, as opposed to 64% of those with low levels of empathy, a difference of 12%.

Figure 17 shows responses to a question asking about efforts to avoid touching one’s own face. Overall, 44% of all respondents stated they try to avoid touching their faces most of the time, while 31% say they always do so. Among those with high levels of empathy, 35% stated that they always try to avoid touching their faces, while 45% stated that they do so most of the time; among those with low levels of empathy the corresponding shares were 26% and 44%.

Figure 18 examines respondents’ willingness to wear a face mask while outside their homes. We see quite a clear difference in this regard between those with high and low levels of empathy. A total of 58% of those with high levels of empathy state that they always wear a face mask when in a place outside the home with at least five people present, while only 43% of those with low empathy do so, a difference of 15%.

Finally, Figure 19 shows respondents’ self-reported willingness to follow their government’s COVID-19 rules. While the majority (61%) of those with high levels of empathy report that they always follow their government’s COVID-19 rules, just 45% of those with low levels of empathy say they do the same, although they are generally supportive of following their government’s COVID-19 rules. In this case, we see a difference of 16%.

Based on the findings presented in Figures 12 through 19, we find more self-reported compliance with COVID-19-related health behavior among those with high levels of empathy then among those with low levels of empathy. Overall, the degree of self-reported compliance with health measures is high; however, we also need to acknowledge that signaling compliance is a socially desirable thing to do during a pandemic and that respondents may therefore be inflating their responses somewhat (Daoust et al. 2020).

On our website, we also examine the way that COVID-19-related health behavior is distributed among supporters of the various political parties in Belgium (Flanders and Brussels, Wallonia and Brussels), France, Germany, Spain, Italy, Poland and the Netherlands. Interestingly, we find little evidence that adherence to COVID-19-related health behavior is highly politicized. For example, supporters of right-wing and left-wing populist parties do not differ to a large extent from supporters of centrist parties when it comes to engaging in COVID-19-related health behavior. These findings stand in sharp contrast to those from the United States, where mask-wearing and compliance with other COVID-19-related health measures have been shown to be highly politicized (Gadarian, Goodman and Pepinksy 2020).

Empathy and views on the EU’s role in the COVID-19 pandemic

In the last section, we explore respondents’ views on the political aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic, for example regarding their thoughts on what the EU’s role in the crisis should be. In Figure 20, we show the average shares of people both in the EU27 as a whole and in our seven individual countries who agree with the following statements:

- “No European country is to blame for the virus.”

- “The EU should play a bigger role in fighting the health crisis.”

- “European countries should work together in the pandemic.”

- “My country is strong enough to deal with the pandemic alone.”

Within the EU27, 72% of respondents agree with the statement that no European country is to blame for the virus. A total of 89% agree with the statement that the EU should play a bigger role in fighting the health crisis. A vast majority of 91% agree with the statement that European countries should work together in the pandemic. Only a minority (47%) of respondents think that their own country is strong enough to deal with the pandemic alone. When we compare the results for the seven countries that we study more in-depth, we see only a single statement for which respondents from different member states report strikingly different views. A majority of Dutch and German respondents (respectively 70% and 60%) agreed with the statement, “My country is strong enough to deal with the pandemic alone,” as compared to minorities in the other five member states surveyed.

Figure 21 shows the responses to the same question, but now split by empathy levels. While we find very few differences with regard to respondents’ views about no European country being to blame for the virus, with a respective 71% and 73% of those with low and high levels of empathy agreeing, we find clearer differences on the other statements. When it comes to the EU playing a bigger role in fighting the crisis, 92% of those with high levels of empathy agree with this statement, as compared to 86% of those with low levels of empathy, a difference of 6%. While 94% of those displaying high levels of empathy think that countries should work together in the pandemic, 87% of those with low empathy do, a difference of 7%. A majority (52%) of those with low levels of empathy thought that their own country was strong enough to deal with the pandemic alone, but only a minority (42%) of those with high levels of empathy agreed, a difference of 10%.

Overall, the findings reported in Figures 20 and 21 suggest that respondents with higher levels of empathy are slightly more likely than those with lower levels of empathy to support European cooperation and a bigger role for the EU. That said, respondents who display comparatively lower levels of empathy are still generally enthusiastic about cooperation with other European countries and within the EU.

Concluding remarks

How does one organize support for collective action in times of crisis? What motivates people to comply with measures to combat a crisis even if they have not personally been touched by its effects? These questions arise again and again when collective action is required. On the European level, issues of shared responsibility and solidarity spring up vigorously as soon as another crisis hits. This goes in particular for the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, which asks for a combination of collective and individual action. Personal habits need to change as well as significant political measures need to be taken to contain the disease and to manage the collateral damage of its spread. The most prominent and discussed example is the wearing of masks. It’s uncomfortable at best, disturbing for many. Most importantly, its primary benefits lie not with protecting the wearer, but with protecting those around her/him. Nevertheless, millions of people worldwide put up with an uncomfortable piece of tissue covering their nose and mouth. They do so because of the slim chance that - even though they don’t feel sick – they are infected and could thus be spreading the virus. In a theoretical thought model, you would be pressed hard to expect a low level of compliance under these circumstances. And yet, it happens worldwide with relatively little resistance. Why is that? We are quick to believe that the world is full of egoism, but the pandemic has revealed that humans do take personal sacrifice for a greater good.

Empathy is one way to explain people’s willingness to invest not only without immediate return, but at a personal cost. Empathy has a good reputation. Contrary to other emotions such as fear and nostalgia (eupinions 11/16, eupinions 11/18), empathy is considered a desirable trait both in individuals and communities at large. It is associated with a warm, caring and pro-social demeanor. Like every emotion, however, empathy also has its darker side. It is prone to lead to ingroup favoritism, enforce insider-outsider phenomena and may thus contribute to conflict and exclusion. And indeed, research shows that empathy happens more easily when it relates to personal experience and/or concerns people similar to us.

In line with this research, we checked for empathy levels in different socio-economic groups and combined it with compliance to COVID-19 health regulations, attitudes towards European integration and political party preferences. To cut a long story short, empathy is lower among the young, the wealthy and those who identify as right-wing. A look at the pre-existing research on the topic, shows that these findings should come as no surprise.

“Categorical boundaries to the extension of empathy also run along socioeconomic lines, but in an asymmetrical manner”, writes Robert Sapolsky in his book Behave. He continues: “What does that mean? That when it comes to empathy and compassion, rich people tend to suck.” (2018/533). He explains this phenomenon by pointing to a wealth of research showing that well off people are more likely to view the existing class system as fair and meritocratic, and to view their success as an act of independence.

Empathy is easy. And empathy is hard. Research shows that when we feel compelled to share the pain of people we dislike or disapprove off, we are prone to experience this as a mental load and shut down. “The process of taking their perspective and feeling their pain is a dramatic cognitive challenge rather than something remotely automatic.” (Sapolsky 2018/534) “Empathy fatigue” can thus be viewed as the state when the cognitive load of exposure to the pain of others whose perspective is challenging to take has exhausted the frontal cortex (Authors note: The frontal cortex is the part of the brain attributed to i.a. executive function, regulation of emotions and restraint of behavior). To sum up: it sure seems like the odds are stacked against empathy towards strangers, outsiders, and others at a distance.

This seems to be particularly salient when it comes to considering the activation of empathy on the European level with its heavy load of historical experiences of hostility and enmity. And yet, it is happening. Time and again, Europeans support each other in times of need. The most recent example being the decisions to take collective action and responsibility in order to fight the economic fallout of the pandemic. Empathic behavior happening against the odds of nature and nurture might be explained by what’s another constant of human behavior: Once empathy has occurred and led to compassionate action “the self-oriented rewards of it are endless (…) The warm glow of having done good, the lessen sting of guilt, the increased sense of connection to others, the solidifying sense of being able to include goodness in your self-definition.” (Sapolsky 2018/547)

The capacity to feel someone else’s pain and to act to alleviate it is part of (almost) every human’s nature. At the same time, it’s no endless resource. It tends to flow more easily towards those who are similar to us. The more different or distant the recipient feels, the more work is required. The more work is required, the less likely an empathetic state is to produce a compassionate act.

The question - particularly in a political context - is: Are our empathy levels and targets set in stone? Are we stuck with how empathic we are and who we feel compassionate towards? Latest research shows: When it comes to humans, nothing is set in stone. We are able to change and adapt in every stage of life. “Through practice, we can grow our empathy and become kinder as a result”, writes Jamil Zaki in The War for Kindness. “Work from many labs suggests that empathy is less like a fixed trait and more like a skill – something you can sharpen over time and adapt to the modern world. Consider our diet and exercise habits (…) If we allow our instincts to take over, we could indulge ourselves into an early grave. But many of us don’t accept this; we fight to stay healthy (…) Likewise, even if we have evolved to care in certain ways, we can transcend those limits. (…) Personality doesn’t lock us into a particular life path; it also reflects the choices we make.” (Zaki 2019/63)

Understanding empathy as a skill rather than a fixed trait also means that it can and must be trained. Research from social psychology shows that regular face-to-face interactions with fellow human beings is of paramount importance for its development. It also shows that the lack of real-life social interaction can compromise empathy and, particularly worth noting in current times, that digital means of communication cannot substitute face-to-face contact in this regard (Turkle 2015). In fact, online life and communication has even shown to be associated with a loss of empathy – particularly in children (Pea et al. 2012). What this means is that one of the ingredients we rely on to tackle the ongoing crisis, namely, empathy, may in fact be compromised by some of the public health restrictions also needed to tackle it. This becomes politically relevant when it comes to prioritizing different public health regulations. Measures, such as school closures as we have seen them during the first wave of infection, that likely compromise people’s willingness and possibly even general capacity to abide by other public health restrictions should be avoided where possible.

Research also shows that empathic behavior can not only be trained, but also triggered (Piff 2012). In experimental settings, test subjects were more likely to show empathic behavior if primed in a particular way. What does that mean for political life? It means that words matter, speech matters, leadership matters. In recent years, this has been demonstrated in European as well as American politics. Political leaders choosing to emphasize otherness, create division that leads to polarization. It works because humans are easily dragged into ingroup/outgroup narratives. At the same time, it hurts in that it hinders another fundamental mechanism of human interaction that makes for the success of us as a species. Humans are deeply social creatures. Human survival and thriving depends on cooperation and mutual support. Not everything that seems to take the shape of altruism, exclusively benefits the receiving party (Andreoni 1989). Giving and taking are two sides of the same coin. This reality can be verbally recognized or distorted and thus shape political outcome and public support. The good news is, that Europeans are ready for European collective action. Our numbers show overwhelming support for European cooperation in the pandemic. European leaders should make good use of it.

Glossary

References

- Alstadsæter, A. et al., (2020) The first weeks of the coronavirus crisis: Who got hit, when and why? Evidence from Norway, NBER Papers, www.nber.org/papers/w27131.pdf

- Andreoni, J. (1989) Giving with impure altruism: Applications to charity and Ricardian equivalence. Journal of Political Economy, 97(6), 1447-1458.

- Baker, Peter (2020) Amid a Rising Death Toll, Trump Leaves the Grieving to Others, The New York Times, 30th of April 2020, www.nytimes.com/2020/04/30/us/politics/trump-coronavirus-grieving.html

- Batson C. D., Jim Fultz & Patricia A. Schoenrade (1987) Distress and empathy: two qualitatively distinct vicarious emotions with different motivational consequences. Journal of Personality, 55(1): 19–39.

- Blair, R. and James R. (2013) The neurobiology of psychopathic traits in youths. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 14: 786–799.

- Bloom, Paul (2017) Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion. Bodley Head.

- Borger, G. (2020) President Trump's coronavirus briefings lack a crucial element: Empathy, CNN.com, 30 March 2020, https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/30/politics/borger-column-trump-empathy/index.html

- Chamorro-Premuzic, T. & Wittenberg-Cox, A. (2020) Will the Pandemic Reshape Notions of Female Leadership?, Harvard Business Review, 26th of June 2020, https://hbr.org/2020/06/will-the-pandemic-reshape-notions-of-female-leadership

- Daoust, J-F., Richard Nadeau, Ruth Dassonneville, Erick Lachapelle (2020) How to Survey Citizens’ Compliance with COVID-19 Public Health Measures: Evidence from Three Survey Experiments. Journal of Experimental Political Science, https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2020.25

- Davis, M. H. (1983) Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 44(1): 113–126.

- De Vries, C. E. (2020) Why the EU struggles to agree on anything Politico, 20th of June 2020, www.politico.eu/article/why-the-eu-cant-agree-on-anything-coronavirus-budget-mff-recovery-fund/

- De Waal, F. (2009) The Age of Empathy: Nature’s Lessons for a Kinder Society. Harmony Books.

- Eisenberg, N., and Miller, P.A. (1987) The relation of empathy to pro-social and related behaviors. Psychological Bulletin, 101(1): 91–119.

- Eisenberg, N., and Strayer, J. (eds.) (1987) Cambridge studies in social and emotional development. Empathy and its development. Cambridge University Press.

- Bohart, A. C., Watson, J. C., & Greenberg, L. S. (2011). Empathy. Psychotherapy, 48(1), 43–49.

- Gadarian, S., Goodman, S. and Pepinksy, T. (2020) The Partisan Politics of COVID-19, Working Paper, https://tompepinsky.com/2020/03/27/the-partisan-politics-of-covid-19/.

- Gerdes, K. E. (2011) Empathy, Sympathy, and Pity: 21st-Century Definitions and Implications for Practice and Research. Journal of Social Service Research, 37(3): 230-241.

- Hodges, S. D. and Myers, M.W. (2007) Empathy. In: Baumeister, Roy F. and Kathleen D. Vohs (eds.) Encyclopedia of Social Psychology, pp. 296-298.

- Jennings, W. (2020) COVID-19 and the “rally-round-the-flag-effect" UK in a Changing Europe, 30 March 2020, https://ukandeu.ac.uk/covid-19-and-the-rally-round-the-flag-effect/

- Montenovo, L., et al, (2020) Determinants of disparities in COVID-19 job losses, NBER Papers, www.nber.org/papers/w27132.pdf

- Pea, R. et al. (2012) Media Use, Face-to-Face Communication, Media Multitasking, and Social Well-Being Among 8- to 12-Year Old Girls. Developmental psychology, 48, 327-336.

- Pfattheicher, S., Nockur, L., Böhm, R. Sassenrath, C., Petersen, M. B. (2020) The emotional path to action: Empathy promotes physical distancing during the covid-19 pandemic. Preprint at https://psyarxiv.com/y2cg5/

- Prinz, J. J. (2011) Is Empathy Necessary for Morality? In: Goldie, Peter and Amy Coplan (eds.) Empathy: Philosophical and Psychological Perspectives. Oxford University Press, pp. 211–229.

- Simas, E. H., Scott Clifford & Justin H. Kirkland (2020) How Empathic Concern Fuels Political Polarization. American Political Science Review 114(1): 258–269.

- Sapolsky, R. M. (2017). Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst. New York: Penguin.

- Turkle, S. (2015) Reclaiming Conversation: the Power of Talk in a Digital Age. New York, Penguin Books.

- Zaki, J. (2017) Moving beyond stereotypes of empathy. Trends in Cognitive Science 21: 59–60.

- Zaki, J. (2019) The War for Kindness: Building Empathy in a Fractured World. Crown: Illustrated Edition.

Method

This report presents an overview of a study conducted by Dalia Research for Bertelsmann Stiftung between 2020-06-10 and 2020-06-30 on public opinion across 27 EU Member States. The sample of n=12,956 was drawn across all 27 EU Member States, taking into account current population distributions with regard to age (16-69 years), gender and region/country. In order to obtain census representative results, the data were weighted based upon the most recent Eurostat statistics. The target weighting variables were age, gender, level of education (as defined by ISCED (2011) levels 0-2, 3-4, and 5-8), and degree of urbanization (rural and urban). An iterative algorithm was used to identify the optimal combination of weighting variables based on sample composition within each country. An estimation of the overall design effect based on the distribution of weights was calculated at 1.29 at the global level. Calculated for a sample of this size and considering the design-effect, the margin of error would be 1 percent at a confidence level of 95 percent.