eupinions audio

NEW! Don’t feel like reading? No worries, we got you. Listen to our new podcast that summarizes all important elements of our most recent study.

Executive summary

In previous reports, such as Fear Not Values: Public Opinion and the Populist Vote in Europe and Globalization and the EU: Threat or Opportunity?, we demonstrated how anxiety due to large-scale societal change is a driver of both polarization and politicization. As we showed in our report Power of the Past, these anxieties also make people more susceptible to the political messages propagated by populist and extremist political movements. Political entrepreneurs on the far left and right of the political spectrum skillfully employ nostalgic rhetoric that casts the way forward as a return to the past.

In this report, we delve deeper into people’s anxieties by focusing on their sense of societal pessimism. We present evidence based on a survey conducted in December 2019 in which we interviewed more than 12,000 EU citizens. Our data is representative for the EU as a whole, as well as for seven member states including Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland and Spain. At the end of this report, we take a look at the ongoing COVID-19 crisis and European governments’ response to it. In particular, we examine what lessons might be drawn from times of crisis-management for politics in general.

Societal pessimism describes the concern that society is in decline and heading in the wrong direction. Interestingly, a rather substantial quantity of people think that their country is not doing well overall, while still being generally quite satisfied with and hopeful about their own lives. This gap between societal pessimism and personal optimism suggests that one source of the considerable anxiety felt by so many people might be the perception that many of the processes that go on outside the bounds of their daily lives and experiences are so complex that they cannot do much about them.

We address this phenomenon through the use of three main questions:

- How optimistic or pessimistic are people about their own personal future and the future of their country, and how does this differ across EU member states?

- How are personal and societal optimism and pessimism distributed among different social groups?

- Do supporters of populist right-wing parties differ in their levels of personal and societal optimism and pessimism in comparison to supporters of other parties?

In the following, we summarize our main findings:

- Within the EU27, we find that while respondents are more optimistic than pessimistic with regard to their own personal future, the opposite holds true with regard for the furutre of their country. A total of 58% of respondents in the EU27 feel optimistic about their personal future, while only 42% feel pessimistic. On the other hand, only 42% express optimism regarding their country’s future, while a full 58% are pessimistic in this regard.

-

Striking variations are evident across countries. France and Italy show the largest shares of people who are pessimistic both about their own personal future and the future of their country. A total of 61% of French people express a pessimistic outlook about their personal lives, and 69% about their country’s future. Similarly, 56% of Italians evince pessimism about their personal lives, while 72% do so with respect to their country’s future. Belgians are split roughly down the middle when it comes to assessing their personal future, but are more likely to be pessimistic than optimistic when assessing the future of their country (with a 64% share expressing pessimism). In Germany, the Netherlands, Poland and Spain, a clear majority of people are optimistic about their personal lives. However, they are far warier about their countries’ futures. The largest “optimism gaps” are evident in Spain and Germany.

-

With regard to generational differences, we find that younger people are more likely to be optimistic about their personal lives than their older counterparts, but are equally pessimistic about their country’s future.

-

Among social and demographic groups, we find the largest optimism gap among the highly educated and women, with 62% of highly educated people being optimistic about their own future, but only 44% being optimistic about their country’s future. Among women, 55% express personal optimism, while only 38% are optimistic about their country's future.

-

When analyzing the data along party preferences, a striking pattern emerges: Those who support far-right populist parties, are – within the context of their country’s electorates – most likely to be pessimistic about both their personal future and their country’s future. The only exception to this pattern is found in Poland, where supporters of the newly founded social-liberal Wiosna party are most likely to be pessimistic about both their personal future and their country’s future.

Introduction

In previous reports, such as Fear Not Values: Public Opinion and the Populist Vote in Europe and Globalization and the EU: Threat or Opportunity?, we demonstrated that many Europeans are anxious. A significant share of Europe’s population expresses anxiety with regard to how their societies will cope with large-scale societal changes due to globalization, migration and automation, among other factors. These very anxieties, as we showed in our Power of the Past report, may also make people more susceptible to the political messages propagated by populist and extremist political movements. Political entrepreneurs on the far left and right of the political spectrum skillfully employ nostalgic rhetoric that casts the way forward as a return to the past.

In this report, we wish to delve deeper into people’s anxieties by focusing on their sense of societal pessimism. Sociologists define societal pessimism as the concern that society is in decline and heading in the wrong direction (e.g., Elchardus and Smits 2007, Steenvoorden 2016, Elchardus 2015). We contrast people’s societal pessimism with their expectations about their own lives. We take this approach because recent evidence from individual European countries suggests that societal pessimism does not necessarily go hand in hand with pessimism about one’s own life, or with worry about one’s own personal future (Elchardus 2015, Schnabel 2018). Indeed, quite the contrary appears to be true: A substantial segment of people think that their country is not doing well while still being generally quite satisfied with and hopeful about their own lives. This apparent gap between societal pessimism and personal optimism suggests that the anxiety felt by a significant group of people stems from these individuals’ feeling that their society is in decline, and that potential solutions are so complex that there is little they can personally do about it. This perception of powerlessness can be an overwhelming feeling.

However, while we are familiar with the contours of societal pessimism and its relationship to people’s expectations about their own lives in some individual countries, we know considerably less about this from a European-wide perspective (for an exception see Steenvoorden 2016). In addition, although there is some evidence to suggest that societal pessimism is most pronounced among supporters of left- and right-wing populist parties (Elchardus and Spruyt 2016, Steenvoorden and Harteveld 2018), we lack a clear European-wide picture. In this report, we provide an in-depth look at the way people view their country’s future vis-à-vis their personal future, and at how this varies across European countries. In addition, we examine whether it is possible to identify specific patterns of societal and personal pessimism across social groups and supporters of different political parties. Specifically, we will address three main questions in this report:

- How optimistic or pessimistic are people about their own personal future and the future of their country, and how does this differ across EU member states?

- How is personal and societal optimism or pessimism distributed among different social groups?

- Do supporters of right-wing populist parties differ in their levels of personal and societal optimism or pessimism as compared to supporters of other parties?

This report seeks to answer these questions by presenting evidence based on a survey conducted in December 2019 in which we interviewed more than 12,000 EU citizens. In doing so, we present two sets of data. One set is based on a sample capturing public opinion in the EU27, while the other completes the picture with a more in-depth focus on respondents from the seven individual member states of Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland and Spain.

The report is organized into five parts. First, we introduce the concept of “societal pessimism”, as well as our methodology for measuring it. Second, we examine the degree to which people are optimistic or pessimistic about their own personal future and the future of their country, and how this differs across the seven EU member states. Third, we demonstrate how personal and societal optimism or pessimism is distributed across different social groups defined by gender, age, employment status and other such demographic measures. Fourth, we contrast levels of personal and societal optimism and pessimism shown by right-wing populist party supporters to those shown by supporters of other parties. Finally, we close with an exploration of what the presence of societal pessimism may mean for European politics, and identify what we see as the most fruitful political responses to it in the future.

Defining societal pessimism

Over the years, there has been considerable interest in the perception of societal decline and how this might relate to the way people feel about the future. Responding in part to the large-scale societal change attributable to rapid technological advancement, advancing economic and political globalization, and climate change, the British and German sociologists Anthony Giddens and Ulrich Beck introduced the notion of a “risk society.” A risk society is a society increasingly preoccupied with its own future, safety and development, thus generating perceptions of increased risk or insecurity (Beck 1992, Giddens 1990, 1991). Beck (1992:50) views the emergence of risk societies as a byproduct of rapid modernization processes such as “surges of technological rationalization and changes in work and organization, (…) the change in societal characteristics and normal biographies, changes in lifestyle and forms of love, change in the structures of power and influence, in the forms of political repression and participation, in views of reality and in the norms of knowledge. In social science's understanding of modernity, the plough, the steam locomotive and the microchip are visible indicators of a much deeper process, which comprises and reshapes the entire social structure."

It is important to understand what kind of mark is left on public opinion by societal developments capable of reshaping the entire social structure. One line of academic work investigating this link uses the concept of societal pessimism. This concept was popularized especially by sociologists, and is used to describe the concern that society is in decline and heading in the wrong direction (e.g., Elchardus and Smits 2007, Steenvoorden 2016, Elchardus 2015, Steenvoorden and van der Meer 2017). Others have focused on the opposite concept, namely people’s optimism about society. Uslaner (2002), for example, examines the effect of optimism on social trust, with optimism in this case relating to the expectation of progress in personal matters or within society as a whole.

In this report, we wish to delineate personal pessimism and optimism from societal pessimism and optimism. In line with Dutch political sociologist Eefje Steenvoorden (2016), we define societal pessimism as the concern among citizens that their society is in decline. By optimism, we refer to the belief that society is likely to do well and will progress in the future. Neither societal pessimism nor optimism are directed toward any specific object or person. They capture a general sense of societal decline rather than the perception that specific elements of society are deteriorating (see also Steenvoorden and van der Meer 2017).

While societal optimism and pessimism capture how people perceive the state of society as a whole, this needs to be contrasted with personal optimism or pessimism, which concerns people’s perceptions regarding their own personal future. There are both theoretical and empirical reasons to distinguish these two forms of pessimism and optimism. On the theoretical front, studies of economic voting – that is, of the extent to which economic evaluations affect voting decisions – distinguish between sociotropic economic evaluations and egocentric economic evaluations (see for example Kinder and Kiewit 1981, Duch and Stevenson 2008). Sociotropic evaluations are judgements of the state of the overall economy, while egocentric evaluations relate to judgments about one’s own personal economic situation. Arguably, a given society’s economy could be doing well at the same time that a specific individual within that society was not doing well economically, and vice versa. The same logic applies to societal and personal pessimism and optimism. Furthermore, there are empirical reasons to distinguish societal from personal forms of optimism and pessimism. Recent case-study evidence from Belgium and the Netherlands suggests that societal pessimism does not necessarily go hand in hand with pessimism regarding one’s own life or worry about one’s own personal future (Elchardus 2015, Schnabel 2018). Indeed, the contrary appears to be true. In his in-depth study of youth in Belgium entitled Beyond the Narrative of Decline, sociologist Mark Elchardus (2015) demonstrated a widespread and persistent belief among Belgian youth that societal prosperity and well-being were in decline, even though the very same young interviewees were quite happy about their own lives and their own future prospects.

Similarly, in his book I'm Fine, But We're Not Doing Well, Dutch sociologist Paul Schnabel (2018) reviewed decades of public opinion data from the Netherlands to show that Dutch respondents are generally very satisfied with their own lives, while at same time believing that their country is not doing well. This evidence suggests that significant swathes of society are anxious because societal pessimism is widespread, with much of this anxiety concerning large-scale, complex problems that individuals feel they cannot do much about.

Against this backdrop, we developed a measure of societal pessimism and optimism, along with a separate measure of personal pessimism and optimism. Specifically, we rely on two survey items for each of these concepts:

- Societal pessimism/optimism is measured using the following question in our eupinions survey: Overall, do you feel optimistic or pessimistic about the future of your country? Those who respond “optimistic” are classified as optimistic about their country’s future, while those who respond “pessimistic” as pessimistic about their country’s future.

- Personal pessimism/optimism is measured using the following question in our eupinions survey: In general, what is your personal outlook on the future? Positive or negative? Those who respond “positive” are classified as optimistic about their personal future, while those who respond “negative” are regarded as being pessimistic about their personal future.

Personal complacency versus societal pessimism

We now turn to the empirical examination of levels of societal and personal pessimism and optimism within the EU27, followed by a more in-depth look at the seven individual countries of Belgium, Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland and Spain.

Societal and personal pessimism within the EU

Figure 1 below displays the degree to which respondents within our December eupinions survey feel either optimistic or pessimistic about their own personal future (displayed on the left), and about their country’s future (displayed on the right). Within the EU27, we find that respondents are more likely to be pessimistic with regard to their own personal future, the opposite holds true with regard to the future of their country. A total of 58% of respondents in the EU27 feel optimistic about their personal future, while only 42% feel pessimistic. On the other hand, only 42% express optimism regarding their country's future, while a full 58% are pessimistic in this regard.

Figure 1 suggests that there is considerable variation across countries. With regard to their own personal futures, German, Dutch, Polish and Spanish respondents follow the overall EU27 pattern rather closely, being more likely to be optimistic than pessimistic. In Italy, 56% of respondents are pessimistic about their personal future, and 44% are optimistic. Respondents in Belgium are split: 50% are pessimistic and 50% are optimistic about their personal future. In Germany, the Netherlands, Poland and Spain, we find many more optimists. A full 67% of Polish respondents are optimistic about their own personal future, with 65% of German, 63% of Dutch and 62% of Spanish respondents showing similarly positive feelings.

When we examine the share of societal optimists and pessimists – that is, those who are either optimistic or pessimistic about their country’s future – we see a considerably greater degree of pessimism. Only in the Netherlands and Poland are respondents split almost evenly between societal optimism and pessimism. A total of 52% of Polish and 51% of Dutch respondents are pessimistic about their country’s future, whereas a respective 48% and 49% are optimistic. However, it must be borne in mind that Dutch and Polish respondents remain much more pessimistic about their countries’ futures than they are about their own personal lives. Italian, French and German respondents show the most pessimism regarding their countries’ futures. A full 72% of Italian respondents are societal pessimists, while only 28% are optimists. In France, 69% of respondents are societal pessimists, while 31% are optimists. Belgium, Spain and Germany fall in the middle, between the comparatively pessimistic Italians and the considerably less pessimistic Dutch. A total of 64% of Belgian respondents and 60% of Spanish respondents state that they are pessimistic about the future of their country, where 56% of German respondents say so about their country.

The key message in Figure 1 is that Italian and French respondents are the most pessimistic national groups in our sample, while Dutch and Polish respondents are least pessimistic. Moreover, when we compare the shares expressing personal optimism or pessimism with the shares admitting to societal optimism or pessimism, it becomes clear that respondents are on average more optimistic about their own personal future than about the future of their country.

Societal and personal pessimism across social groups

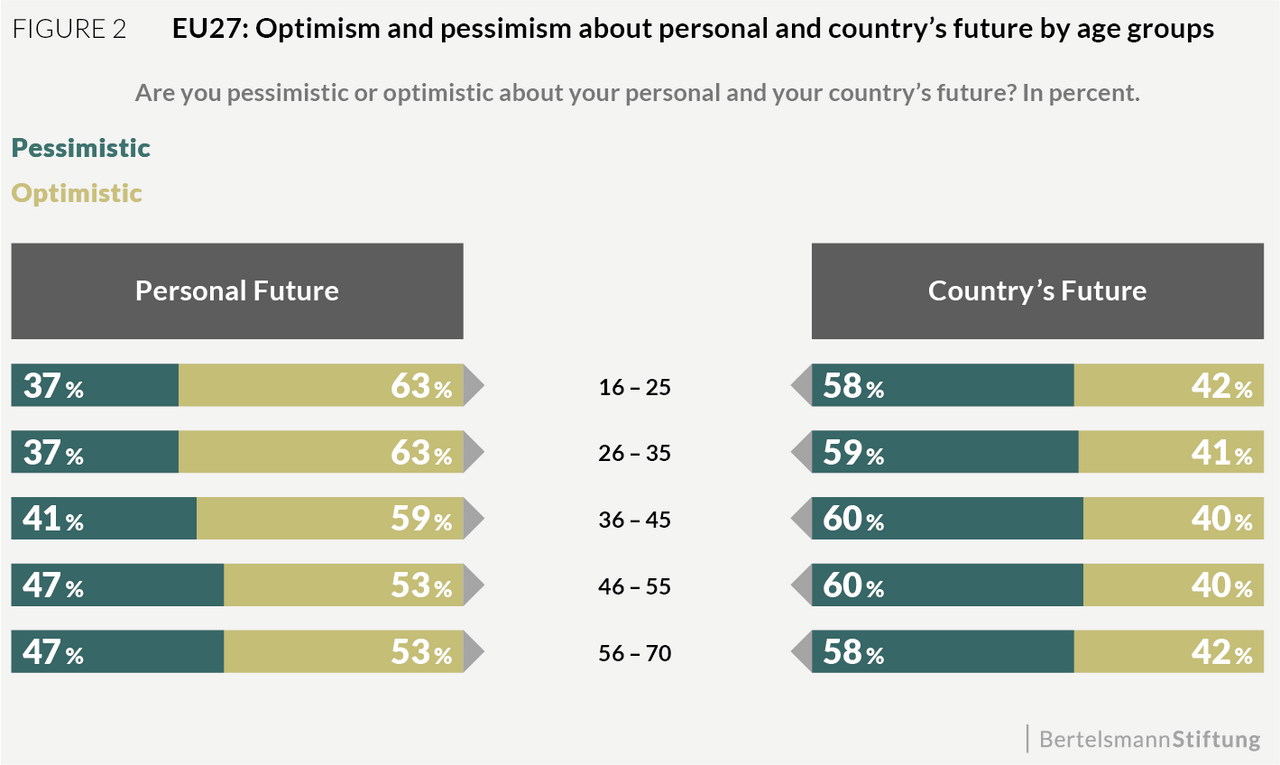

In a next step, we inspect differences across different social and demographic groups. We start with different age groups. Our eupinions survey sample contains respondents ranging from 16 to 70 years old. Figure 2 provides an overview of the degree of personal and societal optimism or pessimism among five different age cohorts: from 16 to 25 years old, 26 to 35 years, 36 to 45 years, 46 to 55 years, and 56 to 70 years. The figure shows that older respondents – that is, those between 46 and 70 years old – tend to be about 10 percentage points more pessimistic about their own personal future than are respondents under 35 years old. There is little difference between the age groups with regard to societal pessimism, with levels ranging only between 58% and 60%. Overall, the results in Figure 2 suggest that respondents across different age groups are more likely to be optimistic about their own personal future than about the future of their country. Overall, age-related differences are evident only in comparing the levels of personal optimism and pessimism expressed by the oldest and youngest respondents.

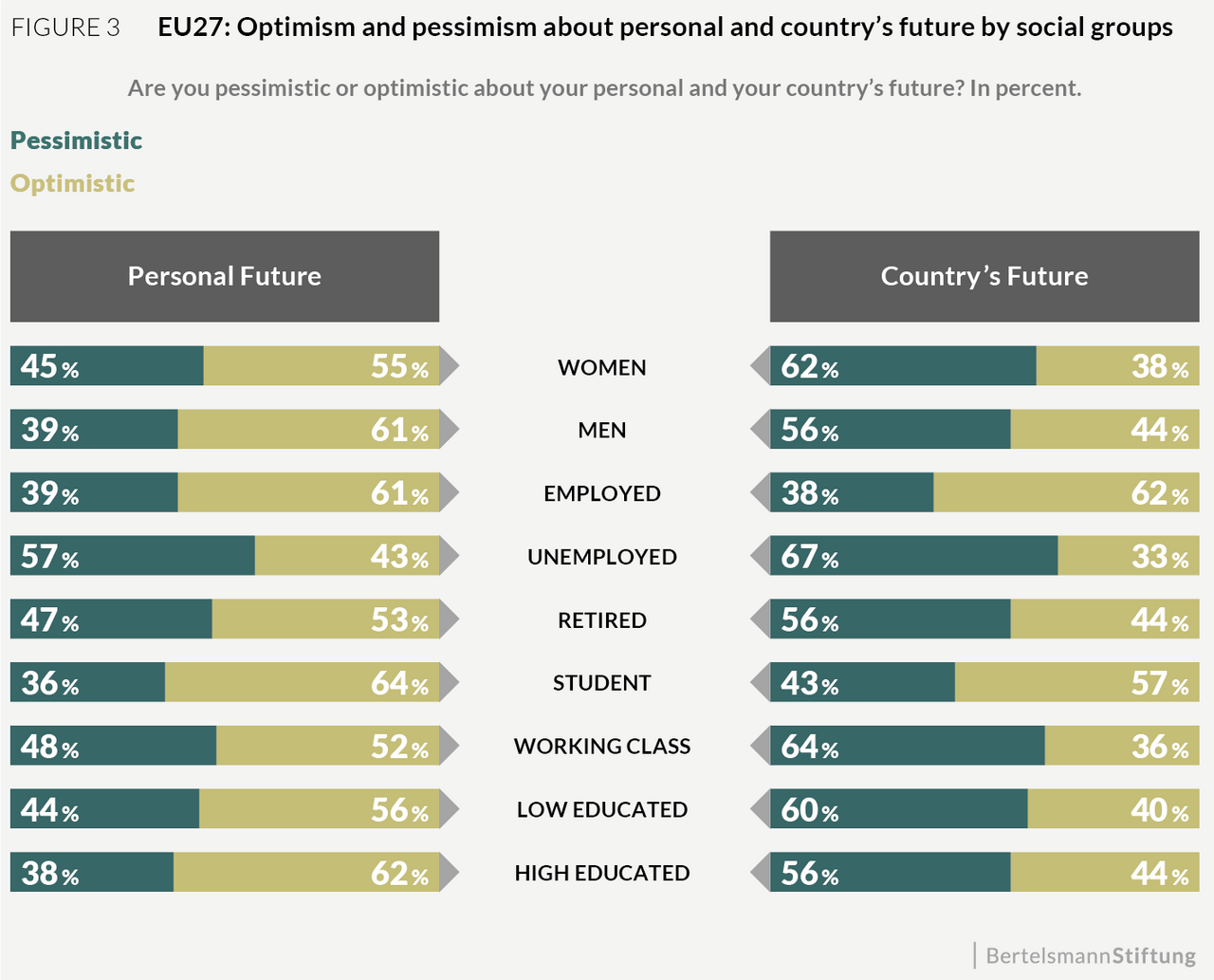

Given that the differences based on age are not great, it is interesting to examine differences based on other social characteristics. Figure 3 displays differences in personal and societal optimism or pessimism based on gender, employment status, social class and education. We will begin with gender. Women are slightly more pessimistic than men both with regard to their own personal future and the future of their country. A total of 45% of women express pessimism regarding their own future, while only 39% of men do so. Correspondingly, 61% of men are optimistic about their own personal future, while only 55% of women are. Women are also more pessimistic than men with respect to their country’s future. Specifically, 62% of women are pessimistic about their country’s future, while 38% are optimistic. Men are also on balance pessimistic about their country’s future, but slightly less so, with 56% expressing pessimism and 44% expressing optimism in this area.

Interesting differences also emerge in the comparison of employed versus unemployed respondents, as well as those who are retired or are still in school. Perhaps unsurprisingly, students, who are generally young, are the most optimistic group with respect to their personal future, with 64% expressing a positive outlook. Respondents who are employed also evince a comparatively sanguine outlook with regard to their personal future, with 61% stating that they are optimistic and just 39% indicating they are pessimistic about their own personal prospects. Retired respondents are on balance only mildly optimistic about their own personal future, with 53% stating that they are optimistic, and 47% stating that they are pessimistic. The unemployed show a much higher level of pessimism about their own future, with 57% expressing pessimism about their personal future, and 43% stating that they are optimistic. We also find similar patterns associated with employment status, with unemployed and retired individuals expressing the greatest degree of pessimism about the future of their countries (respectively with 67% and 56% negative-outlook shares). Students and employed respondents are most optimistic, with a respective 57% and 62% expressing optimism about their country’s future. While retired, unemployed and student respondents display higher levels of societal pessimism than personal pessimism, the levels of personal vs. societal optimism and pessimism expressed by employed respondents are roughly equivalent.

Respondents who identify as working class are quite pessimistic about their personal future, but even more so about the future of their country. A total of 64% of those who identify as working class are pessimistic about the future of their country, while only 48% are pessimistic about their personal future. Finally, those with low levels of education are slightly more pessimistic about the future of their country than are their highly educated counterparts, with a total of 60% of those with low levels of education expressing pessimism in this area compared to 56% of those with high education levels. Those with low education levels are also slightly less optimistic about their own future, with 56% of those with low education levels and 62% of those with high education levels stating that they are optimistic in this regard. Thus, as with several of our other groups, both those with high and low levels of education are somewhat optimistic about their own personal futures, while remaining quite pessimistic about their countries’ prospects more generally.

Societal and personal pessimism among supporters of political parties

In a final step, we examine shares of personal and societal optimism and pessimism among supporters of various political parties. As a part of our eupinions survey, we asked respondents if they felt close to a political party or to no party at all. However, we asked this question only as a part of the in-depth studies we conducted in the seven individual member states of Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland and Spain. In figures 4 through 10, we show the levels of personal and societal optimism and pessimism reported by supporters of specific political parties, as well as those who do not support any party, in each of these countries. Rather than discussing the results for every party, we will highlight the starkest differences we find in our data – that is, specifically between the most optimistic and most pessimistic respondents. An overall pattern emerging from our data is that the most pessimistic respondents are those who feel close to populist parties, especially on the far-right of the ideological spectrum. Similarly, those who are most optimistic are supporters of mainstream parties that hold centrist positions. Only in Poland do we find the reverse pattern. Note that in the graphs we work with the original party names. For translation please check the annex, where you also find data for supporters of other parties and no parties.

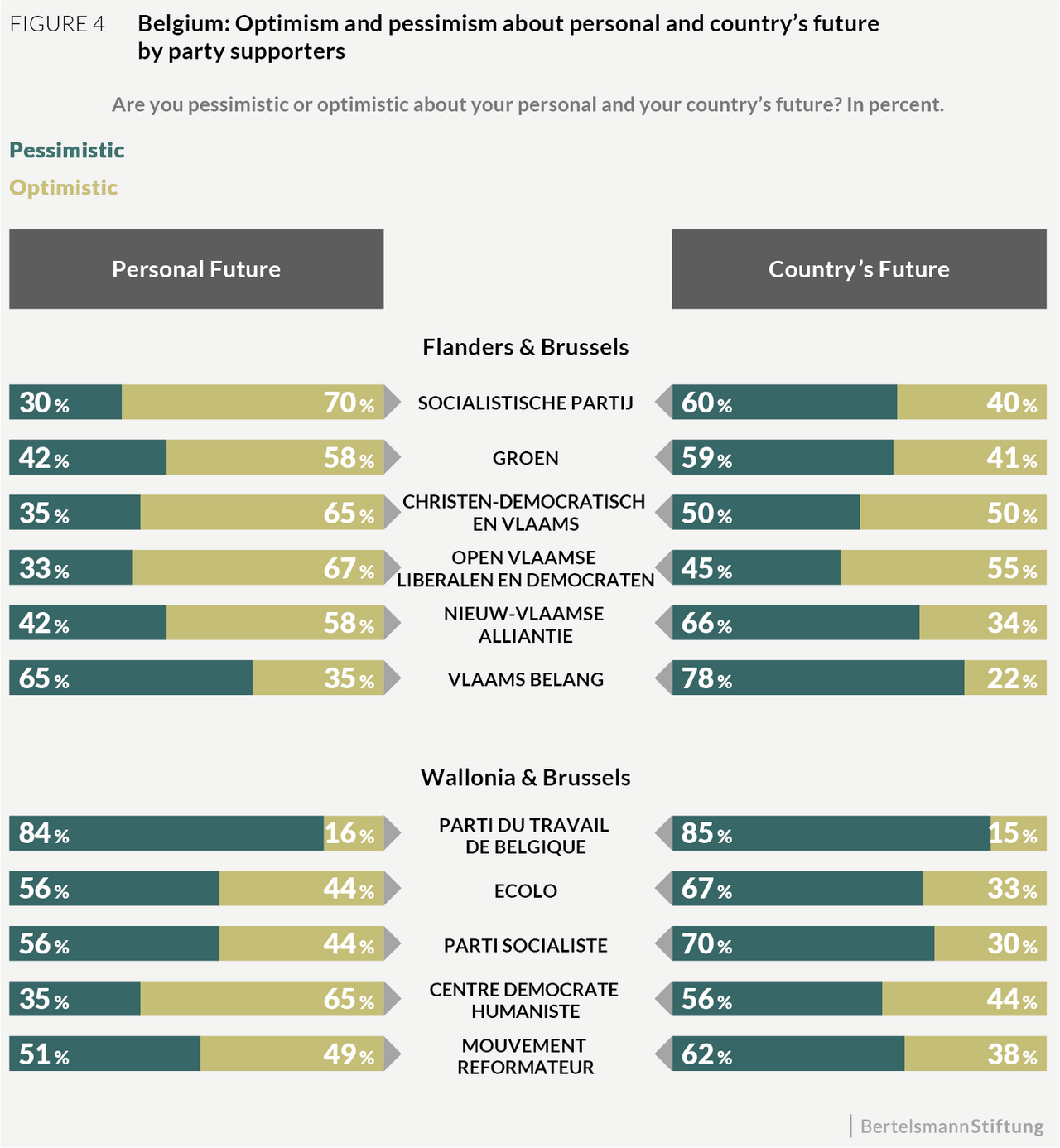

The results for Belgium are presented in Figure 4. Here, the most personally and societally pessimistic respondents are those who state that they feel close to the Flemish Interest (Vlaams Belang) in the Dutch-speaking part of the country and to the Belgian Workers’ Party (Parti du Travail de Belgique) in the French-speaking part. Those who feel close to the Flemish Interest are both pessimistic about their personal future (65%) and about the future of Belgium (78%). Those who feel close to the Belgian Workers’ Party are even more pessimistic, with 84% of these individuals expressing pessimism regarding their personal future and 85% about the future of Belgium. On average, supporters of political parties in Belgium are more pessimistic about the future of their country than they are about their own personal future.

The most optimistic groups among supporters of Belgian political parties are those who support the Liberals (Open Vlaamse Liberalen en Democraten) in the Dutch-speaking part of the country and those who back the Christian Democrats (Centre Democrate Humaniste) in the French-speaking part. A total of 65% of those who support the Liberals in the Dutch-speaking part are optimistic about their own personal future, while 50% express optimism about the future of Belgium. In Wallonia, 65% of those supporting the Christian Democrats are optimistic about their own future, while 44% are optimistic about the future of Belgium overall. However, personal optimism is much more pronounced than societal optimism even among these groups.

Figure 5 displays similar information for respondents who support political parties in France. The most optimistic group here is made up of those who support President Emmanuel Macron’s Republic on the Move (La Republique En Marche) party; 72% of these individuals express optimism regarding their personal future, while 66% have a positive outlook regarding the future of France. By contrast, the most pessimistic respondents in France are clearly those who support the far-right populist party led by Marine Le Pen, the National Rally (Rassemblement National). A total of 82% of these individuals are pessimistic about both their personal future and the future of France. Those who support political parties in France are on average more pessimistic about the future of the country than about their own personal future.

Figure 6 shows the levels of personal and societal optimism and pessimism among supporters of political parties in Germany. The most pessimistic respondents here are those indicating that they feel close to the far-right populist Alternative for Germany (Alternative für Deutschland) party. A total of 66% of individuals supporting the Alternative for Germany party state that they are pessimistic about their own personal future, while fully 90% of this group say they are pessimistic about Germany’s future overall. The views of respondents stating that they feel close to the German Christian Democrats (Christlich Demokratische Union) offer a stark contrast, with 79% expressing optimism about their personal future, and 65% indicating that they were optimistic about Germany’s future. Supporters of German political parties are on average pessimistic about the future of Germany, while quite optimistic about their personal future.

Figure 7 shows our survey results for supporters of Italian political parties. Supporters of the far-right populist League (Lega) party are the most pessimistic regarding both their personal future and the future of Italy. A total of 62% of League supporters are pessimistic regarding their personal future, while 81% are pessimistic about the future of Italy. Forward Italy (Forza Italia) backers are Italy’s most optimistic group of political-party supporters, with 58% expressing optimism about their own personal future, and 40% being optimistic about Italy’s future more generally. Overall, supporters of political parties in Italy are more pessimistic about the country’s future than they are about their own personal future.

Figure 8 provides similar survey results for the supporters of Dutch political parties. The most optimistic respondents here are those who support the social-liberal Democrats66 (Democraten66) party. A total of 86% of Democraten66 supporters state that they are optimistic about their personal future, while 78% are optimistic about the future of the Netherlands. The most pessimistic group is made up of those who support the far-right populist Forum for Democracy (Forum voor Democratie) party. A total of 59% of Forum supporters are pessimistic about their own personal future, while 75% are pessimistic about the future of the Netherlands. On average, supporters of Dutch political parties are much more optimistic about their own personal future than they are about the future of the Netherlands.

Figure 9 displays our survey’s results for supporters of Polish political parties. Here, the most optimistic group is made up of those who support the far-right Law and Justice (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość) party that is currently in power. A total of 89% of Law and Justice supporters state that they are optimistic about their own personal future, while 82% are optimistic about the future of Poland more generally. The most pessimistic group is made up of supporters of the social-liberal Spring (Wiosna) party; among these individuals, 52% state that they are pessimistic about their personal future, while 80% say they are pessimistic about Poland’s future. Clearly, the pattern displayed by Polish political-party supporters is very different than in the other countries featured in our in-depth study, as supporters of the social-liberal party show the lowest levels of optimism, while supporters of the far-right party show the highest levels. One reason for this might be that Law and Justice currently has a strong grip on Poland’s government, and is thus able to determine the country’s policies.

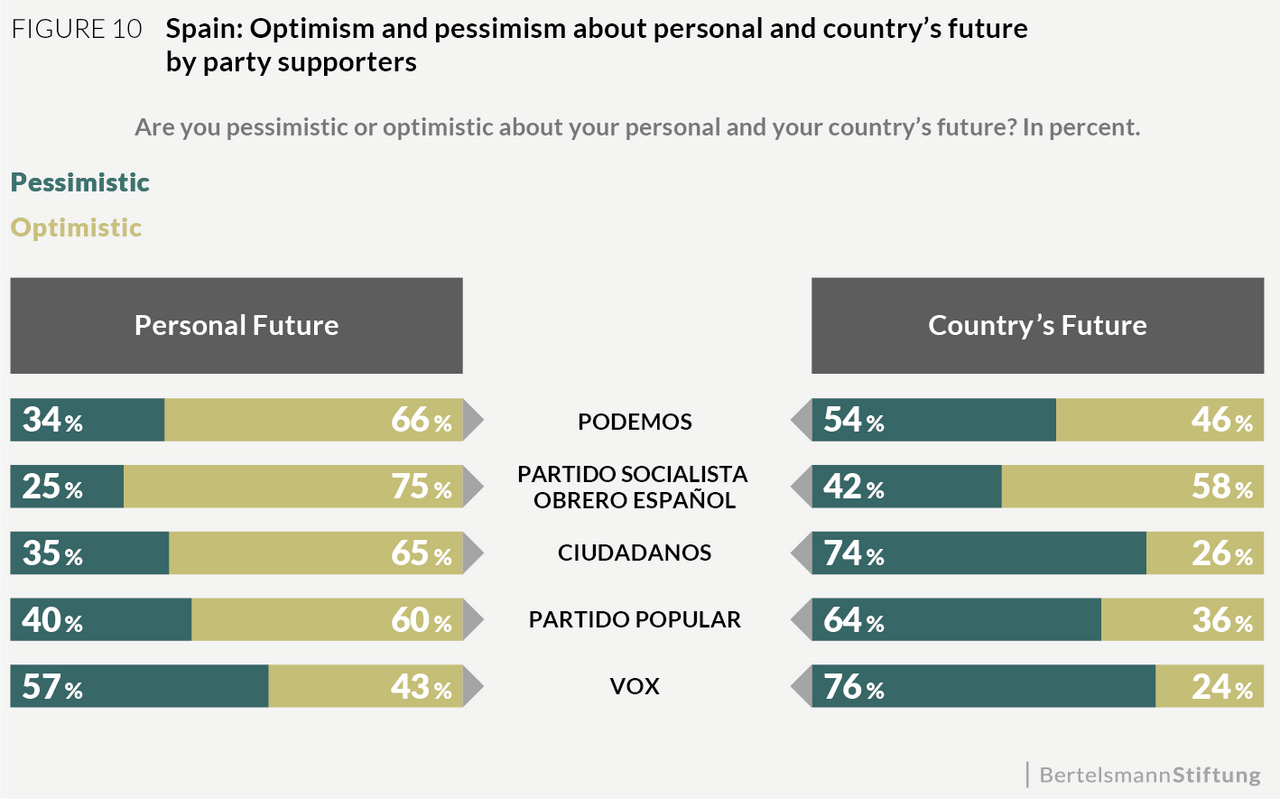

Finally, Figure 10 shows our survey’s results for supporters of Spanish political parties. The most optimistic group here is made up of those who identify with the Social Democratic party (Partido Socialista Obrero Español) that is currently in government. A total of 75% of Social Democratic party supporters are optimistic about their own personal future, while 58% are optimistic about the future of Spain more generally. The most pessimistic group is those who feel close to the far-right populist VOX party, with 57% of VOX supporters expressing pessimism about their own personal future, and 76% being pessimistic about Spain’s future. Overall, supporters of political parties in Spain are more optimistic about their own personal future than they are about the future of Spain.

Two patterns emerge from the data on political-party supporters. First, those who support political parties are on average more pessimistic about the future of their country than about their own personal future. Second, individuals who feel close to parties on the far right of the ideological spectrum are on average quite pessimistic, while their centrist counterparts are on average the most optimistic group. The only country that does not fit this pattern is Poland, where Law and Order party supporters are the most optimistic, and supporters of the social-liberal Spring party are the most pessimistic.

Concluding remarks

Over the years, there has been quite a lot of interest in the notion of societal decline and how it relates to the way people feel about the future. The British and German sociologists Anthony Giddens and Ulrich Beck coined the notion of a “risk society” to describe those societies that experience rapid modernization processes and are increasingly preoccupied with their own future, safety and development, thereby generating perceptions of increased risk or insecurity.

Against this backdrop, our tendency as humans to be overly optimistic about our personal future is cast in a new light (Sharot 2011). When it comes to predicting what will happen to us tomorrow, next week, or years from now, we overestimate the likelihood of positive events and underestimate that of negative events. This is what Tali Sharot has referred to as the “optimism bias.” In this report, we shed light on a related aspect, namely that people are more optimistic about their personal future than they are about the future of their community or society as a whole. A widespread pattern appears to be that while a majority of people believe that they themselves will be fine, they also believe society is in decline.

This optimism bias can be an admirable trait. It strengthens individuals’ belief in their own capacities to cope with the challenges and insecurities of the future. Having said that, the earlier-described optimism gap might also cause a fatal form of passivity. This goes for the tendency to overestimate one’s own resilience as well as for the tendency to underestimate society’s capacity as a whole. While the former might cause passivity due to negligence, the latter might do so out of a personal feeling of powerlessness.

In what follows, we examine both these forms of passivity:

- First, overestimating our personal resilience in the face of imminent danger might well result in inaction which, in turn, further aggravates the situation. The current COVID-19 crisis offers a vivid example. To prevent the virus from spreading, European governments appealed to their citizens’ sense of responsibility by suggesting that they practice social distancing in their daily lives. However, the appeal to individuals’ sense of responsibility and personal risk of infection largely failed, thus forcing governments to enforce legally binding measures. As the New York Times’ Donald G. McNeil Jr. stated on February 27, “in every epidemic that I ever covered, whether it was AIDS in Africa or Zika here, people don’t believe the disease is going to get them until somebody they know gets it and suffers.”

- Second, underestimating our society’s capacity to act in the face of approaching dangers may paralyze rather than stimulate individual action. This applies in particular to existential threats such as climate change, the sheer scale and consequence of which is hard to grasp and seems to render individual action woefully powerless. The imminent threat of rising temperatures and sea levels has not led to a widespread change in people’s individual behavior. It is difficult for individuals to understand that if everyone modifies their behavior somewhat, society as a whole will likely prove more capable of tackling the issue. Commenting on this problem in an editorial published on October 8, 2018, TIME magazine editor Jeffrey Kluger states: “The bad news for environmental scientists and policymakers trying to wake the public up to the perils we face is that climate change checks almost every one of our ignore-the-problem boxes. For starters, it lacks the absolutely critical component – the “me” component. […] Climate change is a huge problem – arguably the biggest of all problems – and that makes individual action seem awfully pointless. We reason that we can curtail things we want to do – like driving or flying, […] but [that] if other people aren’t going to do it, it’s not going to make any difference.”

How can the rhetoric of political leaders help mitigate the tendency for most people to overestimate their own resilience as they underestimate the resilience of society?

In face of the COVID-19 crisis, we observe two types of crisis management by European governments. Some, such as Viktor Orban’s government in Hungary, have used the crisis to massively expand their personal power. Others have sought to act as transparently as possible by reaching out to their citizens and emphasizing their trust in the public to cooperate with measures imposed during these extraordinary times.

As German Chancellor Angela Merkel emphasized in her televised address on March 18: “We are a democracy. We thrive not because we are forced to do something but because we share knowledge and encourage active participation.”

In a similar vein, French President Emmaunel Macron stated in his televised speech on March 16: “The message is clear, the information is readily available, and we will keep passing it on to you.”

Or, as Italian Prime Minister Guiseppe Conte underlined in one of his central crisis statements: “From the start I have chosen to be fully transparent, to share information. I chose not to play down the situation, not to hide the reality.”

These statements reflect a rhetorical strategy to actively address and moderate people’s overconfidence in their own resilience while emphasizing the important role each and every citizen plays in protecting society as a whole. Conte, Macron, Merkel and others convey the message that the danger is real and that in order to fight it, everybody must follow the rules.

At the same time, they demonstrate the state’s capacity and determination to act while explaining every step along the way. Transparency, inclusion, determination and action appear to be the guiding principles of their policy choices and political communication.

It is interesting to see how, in the face of the imminent danger currently threatening all of society, several modern political leaders choose to fully engage with their citizens in terms of the actions taken while being transparent about their own thinking and decision-making. In doing so, they demonstrate trust in their citizens to understand and act accordingly. In return, they see their approval ratings skyrocket. In the political pressure cooker that is the corona virus outbreak, where it is nearly impossible to assess the political, economic and societal impacts, straight talk and transparency in the face of ongoing bad news about choices, risks and consequences appear to be the winning strategy.

There is another aspect of the COVID-19 crisis that politicians might seize as an opportunity: we are all sitting in the same boat. A virus can attack anyone in society. Heads of state, public officials and everyday citizens alike are personally affected by the virus. If anything, the duties of politicians in these difficult times might put them at a greater risk of infection. The current situation offers politicians a chance to demonstrate a form of unity and equality they usually fail to demonstrate. Several cases of prominent politicians carefully documenting their very own COVID-19 experiences on social media, sometimes by allowing highly unusual views into their private homes, suggest that they try to reach out in precisely that way.

Once we have passed the eye in the needle of this virus crisis, there might be a lesson for those working to counter the crisis in trust and credibility that politicians have been facing for many years now. Honest talk about the situation at hand and the choices individuals and societies face do not lead to mistrust and disrespect. In fact, people are likely to feel valued and thus grant their trust in return (Van der Bles et al. 2020; for an initial analysis in the context of the COVID-19 crisis, see Barari et al. 2020). This is a lesson that many figures of authority in society, such as physicians, teachers and judges have had to learn. This simple truth is easily washed over amid the rapid news cycles and info bites of daily politics. Should this combination of transparency, straightforward communication and trust in the public prevail, it could prove to be one of the long-term benefits of this crisis.

Glossary

References

Barari et al. (2020). Evaluating COVID-19 Public Health Messaging in Italy: Self-Reported Compliance and Growing Mental Health Concerns, Preprint, doi: doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.27.20042820

Beck, Ulrich (1992). Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. Sage.

van der Bles et al. (2020). The effects of communicating uncertainty on public trust in facts and numbers, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117 (14), doi: 10.1073/pnas.1913678117.

Duch, Raymond M., and Randolph T. Stevenson (2008). The Economic Vote: How Political and Economic Institutions Condition Election Results. Cambridge University Press.

Elchardus, Mark (2015). Voorbij het Narratief van Neergang. LannooCampus.

Elchardus, Mark and Wendy Smits (2007). Het Grootste Geluk. Lannoo Uitgeverij.

Elchardus, Mark and Bram Spruyt (2016). Populism, Persistent Republicanism and Declinism: An Empirical Analysis of Populism as a Thin Ideology. Government and Opposition 51.1: 111-133.

Giddens, Anthony (1990). The Consequences of Modernity. Polity Press.

Giddens, Anthony (1991). Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Stanford University Press.

Kinder, Donald R. and D. Roderick Kiewiet (1981). Sociotropic Politics: The American Case. British Journal of Political Science 11.2: 129-161.

Kluger, Jeffrey (2020). Why We Keep Ignoring Even the Most Dire Climate Change Warnings, Time, time.com/5418690/why-ignore-climate-change-warnings-un-report/, accessed March 2020.

Macron, Emmanuel (2020) Discours à la nation du président Emmanuel Macron le 16 mars 2020. www.elysee.fr/emmanuel-macron/2020/03/16/adresse-aux-francais-covid19, accessed on March 18, 2020.

Merkel, Angela (2020) An address to the nation by Federal Chancellor Merkel.

www.bundesregierung.de/breg-en/news/statement-chancellor-1732302, accessed on March 22, 2020.

Schnabel, Paul (2018). Met mij gaat het goed, met ons gaat het slecht: Het gevoel van Nederland. Prometheus.

Sharot, Tali (2011) The Optimism Bias: A Tour of the Irrationally Positive Brain. Knopf Canada.

Steenvoorden, Eefje H. (2016). Societal Pessimism: A study of its Conceptualization, Causes, Correlates and Consequences. Netherlands Institute for Social Research/SCP.

Steenvoorden, Eefje H. and Tom W.G. van der Meer (2017). Continent of Pessimism or Continent of Realism? A Multilevel Study into the Impact of Macro-Economic Outcomes and Political Institutions on Societal Pessimism, European Union 2006–2012. International Journal of Comparative Sociology 58.3: 192-214.

Steenvoorden, Eefje H. and Eelco Harteveld (2018). The Appeal of Nostalgia: The Influence of Societal Pessimism on Support for Populist Radical Right Parties. West European Politics 41.1: 28-52.

The Daily. A New York Times podcast (2020) The Coronavirus Goes Global.

www.nytimes.com/2020/02/27/podcasts/the-daily/coronavirus.

Uslaner, Eric M. (2002). The Moral Foundations of Trust. Cambridge University Press.

Method

This report presents an overview of a study conducted by Dalia Research for Bertelsmann Stiftung between 2019-11-27 and 2019-12-16 on public opinion across 27 EU Member States. The sample of n=12,933 was drawn across all 27 EU Member States, taking into account current population distributions with regard to age (16-70 years), gender and region/country. In order to obtain census representative results, the data were weighted based upon the most recent Eurostat statistics. The target weighting variables were age, gender, level of education (as defined by ISCED (2011) levels 0-2, 3-4, and 5-8), and degree of urbanization (rural and urban). An iterative algorithm was used to identify the optimal combination of weighting variables based on sample composition within each country. An estimation of the overall design effect based on the distribution of weights was calculated at 1.25 at the global level. Calculated for a sample of this size and considering the design-effect, the margin of error would be 1 % at a confidence level of 95 %.